|

Woodstock III

"A Day in the Garden"

August 14, 1998

Times Herald Record

August 14, 1998

By Jeremiah Horrigan

Staff Writer

That was then, this is now, at Bethel.

Back then. Day One of the 1969 Woodstock

Music and Art Fair

- The hordes arrive. Route 17B becomes the world's longest two-lane

parking lot.

- We're not in Kansas, but it sure looks it.

- Richie Havens opens the show.

- Hot and sunny skies; weather looks perfect.

- First skinny-dipper sighted.

- One thousand photographers take note.

- Scalpers sell tickets to innocent high school kids.

- Kids save tickets, make collectible killing 29 years later.

- Richie Havens sings for three hours. Main stage construction

nearly done.

- Showers at midnight.

Just now. Day One of the Day In The Garden.

- Route 17B never looked so empty.

- We're still not in Kansas. Maybe Disneyland?

- Afroblue opens at 9 a.m. on tiny second stage. Plays half an hour.

- Cloudy skies look ominously familiar. First sprinkles fall on

press tent, 10 a.m.

- Skinny dipping prohibited without official skinny dipping pass.

- One thousand apply for skinny-dipping review board.

- Scalpers sell bogus parking passes to innocent 48-year-olds.

- Innocent 48-year-olds embarrass their children with their Pete

Townshend windmill-rocker moves.

- Alvin Lee of Ten Years After invites

crowd to boogie. Crowd obliges.

- Illicit bottled water confiscated.

The Times Herald-Record Print Edition

Copyright August, 1998,

Orange County Publications, a division of Ottaway Newspapers

all rights reserved.

|

|

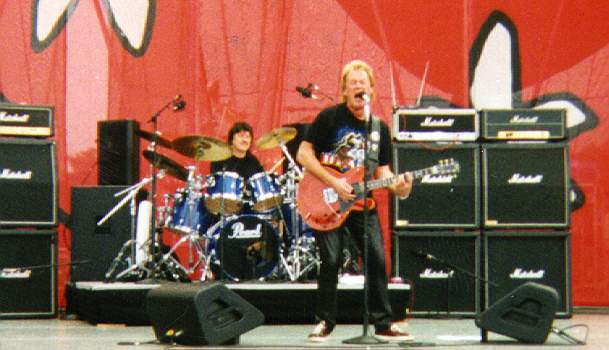

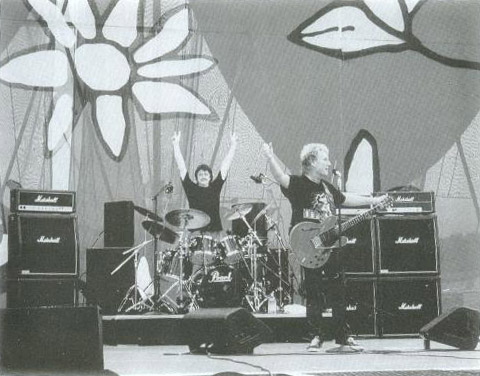

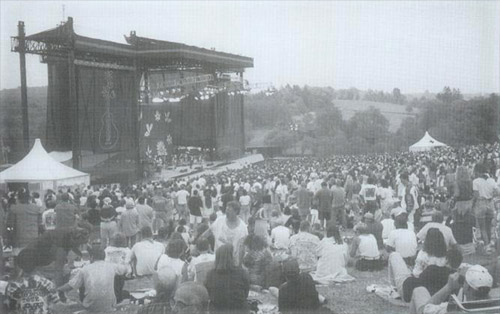

August

14,1998

Ten

Years After return to the site of the original 1969 Woodstock Festival

to perform before 14,000 people at the

“Day In The Garden” Festival. Almost thirty years after their

legendary performance on this farm-site, Ten Years After are introduced

as:

“The

Band Who Rocked The World!”

Their

set list includes the following numbers and is only available on “Bootleg”

CD. The following is from our personal bootleg collection.

- Rock

and Roll Music To The World 3:45

- Hear

Me Calling 5:45

- Love

Like A Man 5:35

- Good

Morning Little School Girl 7:15

- Hobbit

5:35

- Slow

Blues In C 8:15

- Johnny

B. Goode 1:55

- I

Can’t Keep From Crying Sometimes 14:55

- I’m

Going Home 12:15

- Choo

Choo Mama 4:25

- Rip

It Up 3:00

From

a fan:

Wow!!

I just finished watching the live internet broadcast of a Day In The

Garden festival, and the band looked fantastic playing two encores, and

a great version of I’m Going Home…Great Job!!!

|

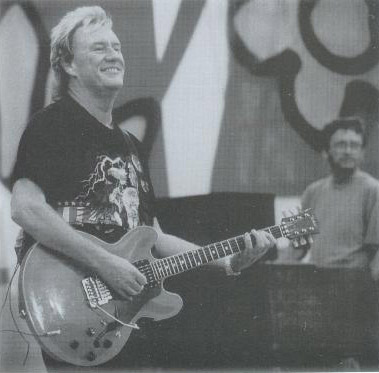

Thanks to Torsten Strube  for this great photo (taken at "Torsten's Garden")

for this great photo (taken at "Torsten's Garden")

'Garden' party isn't epic, but fun

Albany Times Union

August 14, 1998

By Greg Haymes

Staff Writer

BETHEL -- There was a peaceful, easy feeling on Friday at A Day

in the Garden, and it wasn't just because head Eagle Don Henley was

one of the performers.

The vibe was right for an anniversary show on Max Yasgur's Farm

-- the site of the original Woodstock Music and Arts Fair 29 years

ago -- and the music maintained the mellow mood.

Along with Henley, A Day in the Garden hosted headliner Stevie

Nicks, veteran blues-rockers Ten Years After, second-generation

reggae star Ziggy Marley and relatively unknown pop-rocker Francis

Dunnery.

British-born Dunnery might have seemed like an odd selection to

kick off the fest, but it was an inspired choice. The little-known

guitarist-vocalist -- who founded the progressive rock band It Bites

and played in Robert Plant's band before launching his solo career

-- played at Valentine's in Albany just a few short weeks ago, but

he seemed right at home leading his new band on the huge Garden

stage.

In true Woodstock spirit, he opened the fest with

"Revolution,'' but it wasn't a call for political overthrow.

Instead, in true '90s fashion, he sang, "I feel a revolution

inside of me.'' In defiance of the gathering clouds, Dunnery and his

tight backing trio offered the shimmering ballad, "Sunshine,''

but he hit his high-water mark with the back-to-back blast of

infectious, thinking man's pop, "My Own Reality'' and "Too

Much Saturn.''

Ziggy Marley led a sprawling 14-piece band, the Melody Makers,

and it was clear from the opening volley of "Rastaman

Vibration,'' that he wasn't going to shy away from the rich catalog

of song by his legendary father, the late reggae pioneer, Bob

Marley. In fact, it was his father's repertoire that made up the

bulk of the young Marley's 40-minute set, including notable

renditions of the rousing "Get Up, Stand Up,'' and set-closing

"Jammin' '' and a magnificent reading of "No Woman, No Cry.''

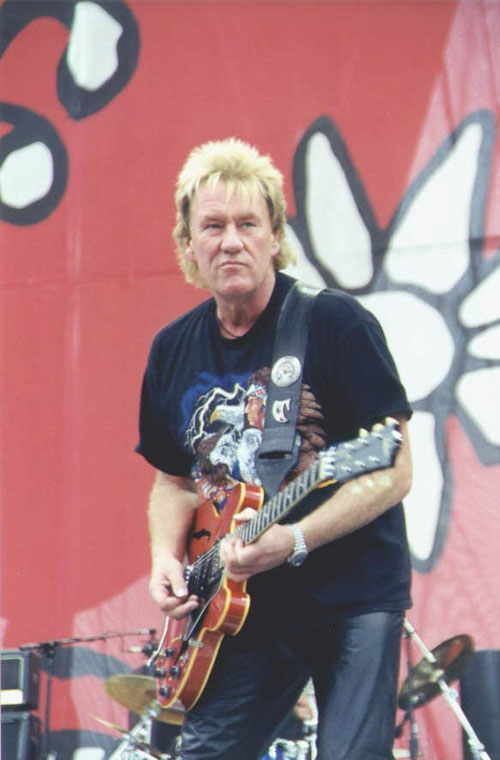

Ten Years After -- the only band on Friday's bill who performed

at the '69 Woodstock fest -- seemed to be something of a curious

museum piece. Despite that, the band featured the same lineup that

they had in '69, their brand of bruising blues 'n' boogie hasn't

progressed or evolved much over the years.

"This is a cool piece of deja vu, huh?'' guitarslinger Alvin

Lee asked the crowd, and, yes, I guess it was, but unfortunately it

wasn't much more. Tired blues classics like "Good Morning,

Little Schoolgirl'' and an ill-advised stab at Woodstock sing-along

with Chuck Berry's "Johnny B. Goode'' fell flat, but they hit

the mark with "I Can't Keep From Crying,'' an epic slab of

psychedelic blues that captured all the best of Woodstock-era jams

while quoting from Cream and Hendrix. Of course, it was all just a

warmup for a reprise of the monstrous "I'm Goin' Home'' from

'69, which Lee stretched out to a whopping 12 minutes, including

forays into the songbags of Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis.

Henley was the musical highpoint of the day, counterbalancing the

peace 'n' love nostalgia with a biting dose of California cynicism.

Backed by a six-piece band and trio of blond bodacious vocalists,

Henley opened with "The Boys of Summer,'' featuring the

anti-nostalgia lyric, "Don't look back, you can never look

back.''

"This is for Bill,'' he said, dedicating his swipe at media

muckraking, "Dirty Laundry,'' to President Clinton. He offered

scathing readings of Leonard Cohen's "Everybody Knows'' and

John Hiatt's "Shreddding the Documents,'' before really going

for the throat by dedicating "The End of the Innocence'' to the

memory of Max Yasgur. "Max, you had a beautiful farm. I

understand that it's not going to be that way for much longer, but

this is for you, Max.''

He also tossed in a weird reggae version of "Sit Down,

You're Rockin' the Boat'' from the Broadway musical "Guys and

Dolls,'' and, of course, he also ran through his hits -- most

notably the gutwrenching "The Heart of the Matter,'' the

cinematic "Sunset Grill'' and the rocking "I Will Not Go

Quietly.''

But he didn't touch his wealth of Eagles' material until his

double-barreled encore when he got behind the drums for "Hotel

California'' and the haunting "Desperado.''

Nicks seemed anticlimactic after Henley's tour de force, although

it didn't help matters any that the rains finally came down at the

start of her start and lasted for about an hour. It was the final

date on Nicks' Enchanted tour in support of her three-CD boxed set,

and she pulled out songs from throughout her career. Backed by seven

musicians and two vocalists, Nicks was at her best on "Stand

Back,'' "Gold Dust Woman'' and a set-closing medley of "Nightbird''

and "Edge of Seventeen,'' but her constant costume changes

destroyed the momentum of the performance. The rain did, however,

keep her trademark twirling to a minimum.

Was Day One of A Day in the Garden a musical milestone? Hardly.

Was it magical? Not at all. Was it fun? You bet.

As Henley sang in "Hotel California,'' "We haven't had

that spirit here since 1969.''

Greg Haymes is the pop music writer for the Times Union.

The Albany Times Union

Copyright 1998,

Capital Newspapers Division, of The Hearst Corporation, Albany, N.Y.

all rights reserved.

|

|

CHUCK LEVEY

Back to the land: Woodstock cinematographer returns for a filmic

look back...

Woodstock: Three Days of Peace and Music has been called the

greatest documentary film ever made.

According to Warner Bros., it is the highest-grossing documentary of

all time. Winner of the 1971 Academy Award for Best Feature

Documentary, Woodstock brought spectacle and a grand scale to the

documentary form. As a concert film, the collection of talent

remains unequaled. And as historical chronicle, it quickly became

emblematic of an era and a generation of Americans. In a review of

the recent release of the director's cut of the film, critic Roger

Ebert said, "What other generation has so completely captured

its youth on film, for better and worse, than the Woodstock

Nation?"

Almost 30 years later, a smaller group of filmmakers set out to

document a commemorative concert on the same site called A Day

in the Garden, named for a line in the

Joni Mitchell song Woodstock.

One filmmaker, Chuck Levey, was involved in both productions, giving

him a unique perspective on the evolution of filmmaking technology

in the intervening years.

1969...

Michael Wadleigh and his Paradigm Films partner John Binder had been

exploring various high-impact film techniques while making civil

rights films and diverse clips for Merv Griffin television specials.

Early on, they were mixing rock and roll with the political,

intercutting Ray Charles and James Brown with Dr. Martin Luther

King, Jr. They knew they had something special on their hands. Many

of the elements that would set Woodstock apart as a visual

experience — multiple images on the screen, high quality audio,

and freely moving, handheld cameras — were discovered and refined

on these projects. According to Wadleigh, these earlier films were

one key to his winning the Woodstock job. The other was his

willingness to put up his life savings.

The filmmakers decided on 16mm blown up to 70mm. 35mm had been

rejected as too expensive and bulky. Eclair NPR 16mm cameras, the

state-of- the-art 16mm camera in 1969, gave them the portability to

capture the spontaneity and energy of the event. "That

portability would really impact content," says Wadleigh. "The

eventual dimensions of the film were obviously important to us, but

in selecting 16mm, we chose the instrument that was appropriate to

catch what was happening."

The blowup would set Woodstock apart. "The other concert

documentaries and music films out at that time had been flops

financially," Wadleigh recalls, pointing out Monterey Pop,

Don't Look Back and several Beatles films. "We had this idea

that a big, World's Fair-style enveloping experience was the proper

approach. We wanted the audience to feel like they were taken there."

A custom-built Technicolor lens would provide single-generation,

liquid gate blowups, with opticals done simultaneously. The lens was

simply aimed at various parts of the 65mm frame to produce the

trademark multiple images now so familiar to anyone who has seen the

film.

Careful editing was facilitated by the use of the first Kem editing

machines in the United States and eight Graflex projectors, equipped

with zoom lenses, which could be synced by plugging them into one

junction box. Wadleigh and co-editor Thelma Schoonmaker, who would

go on to become Martin Scorsese's permanent editor, planned the

opticals and laid out grids for the entire film, and then oversaw

the lab work at Technicolor.

The 70mm projection prints afforded six channel stereo sound, as

opposed to the more common optical soundtracks that limited previous

concert films. The result was a stunning theatrical experience that

had people dancing in the aisles at theaters across the country.

"We knew we wanted the six track sound from the beginning,"

says Wadleigh. "That was a huge advantage. You could just blow

people out of the theater."

Cameraman Chuck Levey, who had studied painting at Rhode Island

School of Design, knew Wadleigh and had worked with him on several

projects, including an Aretha Franklin concert filmed in Providence,

Rhode Island. A self-described, 28-year-old hippie at the time,

Levey was making a living in filmmaking "outside of the

mainstream", and he was already holding tickets when he got the

call to help document the massive festival. Little did he know that

30 years later he would return to the site to direct and help

photograph a sequel of sorts.

"There were a total of 12 cameras, with six or seven guys

shooting at any given time"

The production itself was a Herculean undertaking. Eventually 120

miles (633,600 feet or 193,122 meters) of footage were exposed.

"It was certainly much more of a struggle back then, to shoot

on the run like that," Levey recalls. "There were a total

of 12 cameras, with six or seven guys shooting at any given time. We

had AC-powered Eclair NPR cameras, plugged into 60 cycle AC. A 60

cycle tone was on one of the eight tracks of the music recording.

"To help in lining up picture and sound in post, I tried to get

a shot of my watch at the head of each roll shot on stage. Needless

to say, it rarely happened. As each camera roll went on the camera,

the assistant wrote the time of day and

the performer, as well as the cameraman's name, roll number, etc.,

on the tape that was wrapped around the magazine (and eventually the

film can)."

The plan was simple. Wadleigh had assigned the cameramen only rough

zones in which to shoot. "That was his only direction,"

says Levey. "'Ride it out. Let it rip.'"

When the rains came and the performances were temporarily halted,

Levey ventured out in the mass of humanity with his camera, now with

a battery-powered motor. The motors in the cameras were

interchangeable, with a synch generator built in and a synch cable

connected to a Nagra. This footage of the revelers would be crucial

to the success of the film as an historical document. "Being on

the stage was a lot of fun," he recalls. "But as a

documentary cameraman, I was most comfortable 'out there'."

Most of the time, Levey and the other cinematographers loaded their

cameras with Ektachrome Commercial 7255* film, rated at an EI of 25

in tungsten light. "During the day

I had an 85 filter on most of the time," Levey continues.

"That left me with an ASA of 16. We were often pushing the film

a stop already [at night] and, remember, this was destined for

blowup to 70mm. But it was a pretty fine grain film, and even though

it was blown up, with the multiple images on screen, one image is

rarely filling the whole frame."

Wadleigh agrees. "Without question, without Kodak, there

wouldn't be a Woodstock movie," he says. "That ECO stock

was the beginning, middle and end of it. If we hadn't had that image

on that material, we could never have done the 70mm blowup. Kodak

was very honest with us at the time, and they were so helpful in

working through the problems and selecting the proper print stock.

They and Technicolor were invaluable."

1998...

When Kodak's Steve Garfinkel heard about a 1998 reprise of Three

Days of Peace and Music, a new music festival on the old site in

upstate New York to be called A Day in

the Garden, he decided it was important.

The concert was to be performed by newer pop acts as well as several

original Woodstock performers, including Pete Townshend and Alvin

Lee. Garfinkel contacted Peter Abel, President of Abel Cine Tech,

a friend and fellow documentary aficionado. By coincidence,

Garfinkel had recently met Levey. A trip to the festival site ensued,

along with another coincidence: upon their arrival at Yasgur's Farm

they encountered the new festival's organizers, who informed them

that no arrangements had been made for the filming of the

fast-approaching event.

"...the film would grow to include other subjects: the

evolution of filmmaking technology as exemplified by the two

productions"

Time went by, and the project began to snowball. Eventually the film

would grow to include other subjects: the evolution of filmmaking

technology as exemplified by the two productions, interview footage

with participants and local characters, and the impact of the event

and the generation it came to symbolize.

Levey would act as director/cameraman. More talent was drawn to the

project, including line producer Richard Dooley, production

coordinator Mary Cesar, and her assistant, Amy Baker. Award-winning

cinematographer David Sperling and Baltimore-based filmmaker Peter

Mullett joined up, along with sound recordist J.T. Tagaki. Garfinkel

acted as producer and fourth cinematographer. Vicki Kasala would be

still photographer, with additional stills being shot by the

legendary Elliott Landy, the official Woodstock photographer in

1969, and Chester Whitlock, a freelance concert-shooter. Peter Abel

and Abel CineTech would bring more than a million dollars worth of

equipment to the production. According to Levey, there were

similarities in the approaches to filming Woodstock and A Day

in the Garden. But the newly-assembled

crew worked with the benefit of 30 years of advances in production

and postproduction technology.

"The difference between the reversal stocks that we had back in

1969 and the Vision films that we have today is more like a

revolution," says Levey. "The latitude, sharpness, fine

grain, blacks that are black that you can still see into. We used

both Vision 200T and Vision 250D, and I doubt that anyone could tell

them apart."

Some 75,000 feet (22,860 meters) were shot that week, with

laboratory developing and selected roll printing done at Colorlab of

Rockville, Maryland. Postproduction telecine and editing was done at

SMA Video, in New York City.

"In 1969, we shot the performance material using AC power in

order to stay in sync. It was clumsy. There were cables. The motors

were heavy and became very hot. In the rain we kept getting shocked.

And don't forget our primitive 'get a shot of your wristwatch'

attempts at time code.

"In 1998, with AatonCode, we could just turn on the camera and

shoot," says Levey. "Syncing is automatic with the Aaton

InDaw system. And the 800-foot (244 meter) magazines are much more

convenient. You didn't have to think about running out of film. If

you think of a song being five minutes long, you can get four of

them on an 800-foot-roll. They are a few pounds heavier but they are

balanced so well with the camera that the extra weight doesn't

matter."

Each camera was synchronized by way of an Aaton 'Origin C' master

clock. The same code was fed to the 48-track sound truck, stereo DAT

recorder and the 'smart-slates' Each camera was synchronized by way

of an Aaton "Origin C" master clock. The same code was fed

to the 48-track sound truck, stereo DAT recorder and the "smart-slates".

The Aaton cameras "burn-in" man and machine-readable code

along the perforation edge of the film, making syncing virtually

automatic.

The final link in the film sound system is Aaton's InDaw computer.

The InDaw allowed the filmmakers to automatically post-sync audio

instantly. Using a Jaz drive, Garfinkel fed the 21 hours of recorded

concert material from DAT to Jaz cartridges, which are high-capacity

removable hard drives. This rendered all the audio random-access

instantly available.

With a laugh, Levey compares the new syncing technologies to those

of the original film. "We were glad when it came to the footage

of The Who, because Pete Townshend's trademark windmill guitar

technique made syncing that passage a little easier," he

recalls.

Epilogue:

Over the years Levey has garnered nine Emmy nominations and four

Emmy Awards. He has remained loyal to the documentary form and to

film. "I never fell in love with video like I did film,"

he says. "Film is a completely different medium. I've shot

plenty of videotape, and I feel that film is still the better way.

Clearly, in the long run, it lasts longer. If Woodstock had been

shot on video — which was impossible at the time — we wouldn't

have it today. When things go widescreen, what form is the videotape

going to take? On the other hand, with film, it doesn't really

matter. You'll have the quality images no matter what.

"Technological advancements have made the cinematographer's job

a lot easier since the old days," he says. "The job got

done in 1969, but with much more difficulty. Having done it both

ways, I'll take easier."

*Eastman Ektachrome Commercial 7255 (EI25) process ECO-1 was

introduced in 1958. It was replaced in 1970 by Ektachrome Commercial

7252 which in turn was discontinued in 1986.

From "Making

Films In New York" comes this article from the October 1970

issue of this magazine.

It concerns Woodstock

as "The Longest Optical" and explains in very clear detail

how the Woodstock movie was filmed and why. "Ten Years After

offered us a simple optical solution. We filmed only one number of

this group, that everlasting encore, Goin' Home. We began filming

with three cameras. Mid-Way, one of the cameras ran out of film.

When we saw the rushes together with the sound, we realized right

away we had to show Alvin Lee, the lead performer in triple image.

So at the point at which the third camera ran out of film, we simply

took the continuing image from the right side, flipped it, and let

it run on the left side to continue the triple image optical

throughout. It is also a sequence that has very few cuts. When

filmed, the sequence ran eleven minutes; in the final edited version,

it runs nine."

|

| Different vibes at Woodstock

'98

29th anniversary concert draws a respectable orderly

audience

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

BETHEL, N.Y. For Mike Kowalik, there was one obvious difference

between the original Woodstock and this

weekend's three-day anniversary concert at Max Yasgur's old farm.

"You know what's good about this one?" he asked. "A lot

of toilets.'

Kowalik, 55, said that while he relished the joyful chaos of the

original concert, he appreciated the more organized '98

version that kicked off Friday.

Dads and kids swayed to reggae, bottled-water drinkers outnumbered pot

smokers and concert; staff gave parking directions to beige mini vans

instead of warnings about brown acid.

"It's a completely different scene," said Mike Feinstein,

who wore a tie-dyed Grateful Dead shirt and fiddled with a cell phone.

"We're grown up hippie's now. We have responsibilities."

Patrons were greeted with everything from an espresso kiosk to 400

port-a-potties.

Security guards on horses and all-terrain vehicles prowled the

festival's perimeter to avoid a repeat of the mass gate crashings of

1969 At least one Woodstock tradition held

true; evening rain fell on the crowd as headliner Stevie Nicks

performed.

Promoters of "A Day in the Garden," which continues this

morning, estimated that about 12,000 or more of the 30,000 tickets

available for Friday's show were sold.

Slow ticket sales had prompted a two-for-one ticket promotion.

Concert-goers; who spread their blankets on the massive sloping

hillside Friday had elbow room as Don Henley and Stevie Nicks

performed.

The concert attracted a fair share of people who

showed up for the original concert 80 miles north of New York in 1969.

They found a site transformed from scruffy to respectable --- just

like many of them.

"How can it be the same spirit? I'm 29 years older." said

Frank Vania, who showed up in Bethel with the same friend he brought

in 1969.

The festival was scheduled to continue through today. Woodstock

veterans Pete Townshend and Richie Havens performed yesterday, along

with Joni Mitchell.

Today is reserved for younger acts like Third Eye Blind and Goo Goo

Dolls.

Ten Years After was the only original Woodstock

band on Friday's bill.

|

Get

Back--Woodstock 98...NOT!

by Haven James - posted August 1998

Preview: A Day In the Garden

Festival at Bethel

|

|

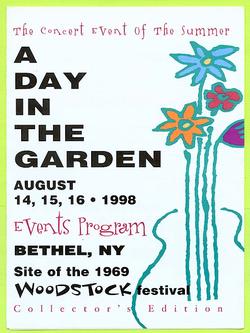

Day-tripper, yeah? Hard to imagine seeing Lou Reed in the sunshine, but stranger

things have happened. Reed, Joni Mitchell, Pete Townsend and a bouquet

of assorted veteran rock 'n' rollers will gather for A Day In

The Garden at Bethel this weekend [8/14--8/16, 1998] on the

original site of the 1969 Woodstock Music & Arts Fair. Though the

event marks the 29th anniversary of a generation's four days of infamy

on the late Max Yasgur's fertile pastures, make no mistake--this is not

Woodstock '98. Leave the tepee, cooler and camping tools home; just

bring cash and credit cards, maybe a folding chair or blanket, an

umbrella just because, and your reading glasses so you can study the

rules, like no cameras or picnic baskets (there will be food and

crafts booths to fill your needs).

The Gerry Foundation is now the owner of the

Woodstock Festival site and Alan Gerry and his associates have set out

to present this three-day daytime only event in a very designed

manner. Mike DiTullo, one of the coordinators of the festival, offers

the following perspective on the venue: "Our long-range plans are

to develop a permanent international attraction that's based on

American performing arts and music. This year, this is sort of like

our maiden voyage; we thought we would have a day in the garden, [so]

that's what we're calling the festival. [It's] three separate days,

it's not a Woodstock reunion, it's nothing like Woodstock.

We're limiting this to 30,000 persons a day. There's no overnight

camping; we're shooting for an older demographic, the baby-boomers

between 25 and 50/55, [and] we're looking to do just a nice two days

of music and fun. The third day we're targeting a younger

demographic--it's more modern, or alternative rock, you know, with the

Goo Goo Dolls and Marcy Playground. So what we're trying to say is the

first two days we're recognizing, and maybe showing our respect for,

the classic rock or the Hall of Famers, and then the third we're

saying that we're also thinking about the future and there are some

rookies out there that we also want to acknowledge and feature."

So, from the production standpoint, this is

not the same old ruse crew of likely suspects. It is a new,

well-funded, and, at least on paper, highly organized unit with

long-range plans, goals, and targets with pictures and arrows on 8x10

glossies. No, Arlo won't be there, but of course Richie Havens will,

along with Ten Years After, Melanie, and Pete Townsend. That's about

it for returning veterans of '69.

An enticing thing about the remainder of the

big acts scheduled is that many of them are not often seen in this

area. Friday brings Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers (noon), Ten

Years After (1:30), Don Henley (3), Stevie Nicks (5), and late

addition Francis Dunnery. Saturday features Donovan (11 a.m.), Havens

(noon), Lou Reed (1), Joni Mitchell (3), and Townsend (5).

Even bigger news for some locals is the

appearance of a bevy of area bands throughout the three-day affair.

DiTullo and his assistant, Susan Leventoff, filled us in on these

blossoming poppies. "We have hired around 15 to 20 local

performers who will be playing throughout all three days. There is a

second stage so they'll be playing before the headliners and then in

between the headliners," DiTullo says. Ulster's own Perfect

Thyroid will open the show Sunday morning on the Main Stage. They'll

be followed by Dishwalla, Joan Osborne, Marcy Playground, Goo Goo

Dolls, and Third Eye Blind.

An almost-final list of the area bands booked

for Stage Two follows: Starting Friday at 9 a.m. they are Afroblue,

the Larry Hoppen Band, the Mountain Laurel Band, Pottersfield (who

wrote the festival song, "Day In The Garden"), Ellen Avakian,

Barclay Cameron, Micheal Kroll, and Whatch. Saturday brings Barbara

Paras, Gavin DeGraw, New Frontier, Greg Press, Dan Sherwin, the Rausch

Bros., the Don Lewis Band, and Blues 2000. Sunday wraps with Borilis,

The Works, The Flies, Wonderkind, Leslie Nuchow, Girlfriend, Jimsons

Lyric, and Trinket. And there were still discussions in process about

adding a few more Woodstock (the town) artists to the lineup, maybe

Justin Love's Big Red Rocket and the Dharma Bums. "That's quite a

lot of local talent we're featuring, and we're proud to do that,"

DiTullo says. "This is a great opportunity for these acts to be

playing with legendary performers."

The report from Bethel is that the

infrastructure is set and the site is ready to rock. Word is that it's

almost surreal there, and isn't that the way a garden is supposed to

be? Tickets are sort of surreal at this point, too. They are now

two-for-one, approximately $70 per day (for a pair) Friday and

Saturday and half that for Sunday. They can be purchased through

TicketMaster by phone or ordered directly using the www TicketMaster

or through the Day In The Garden website.

|

|

|