|

|

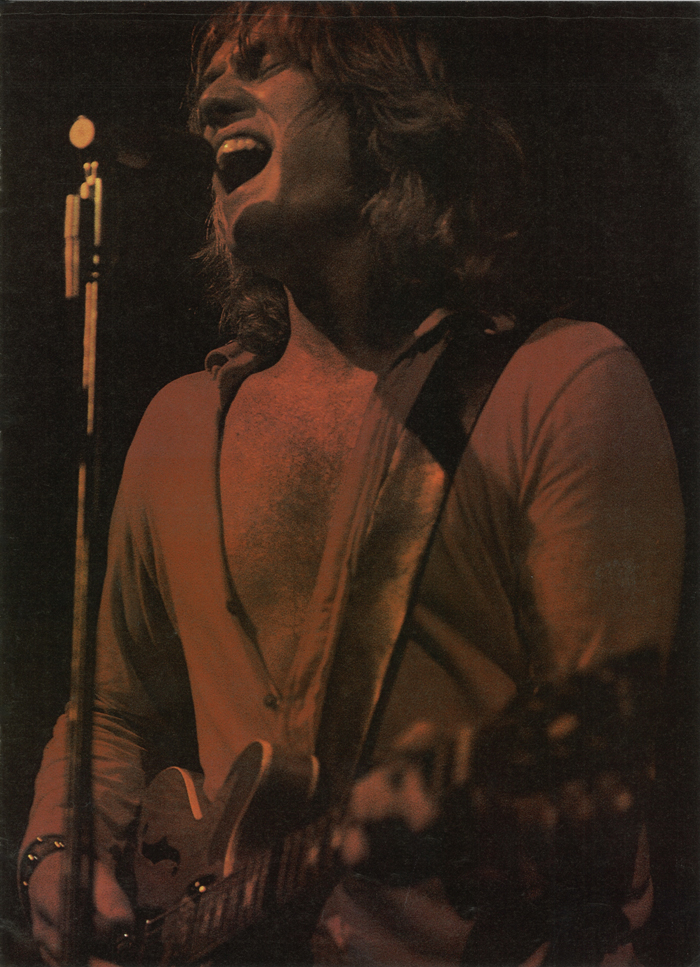

Photographer:

Ed Caraeff

|

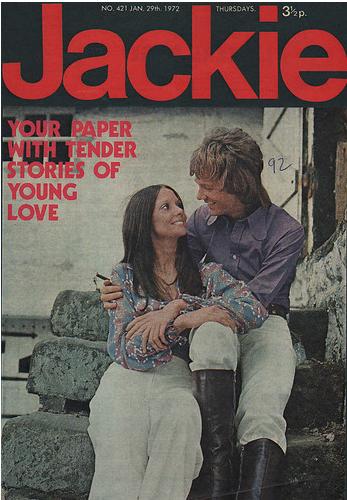

Record

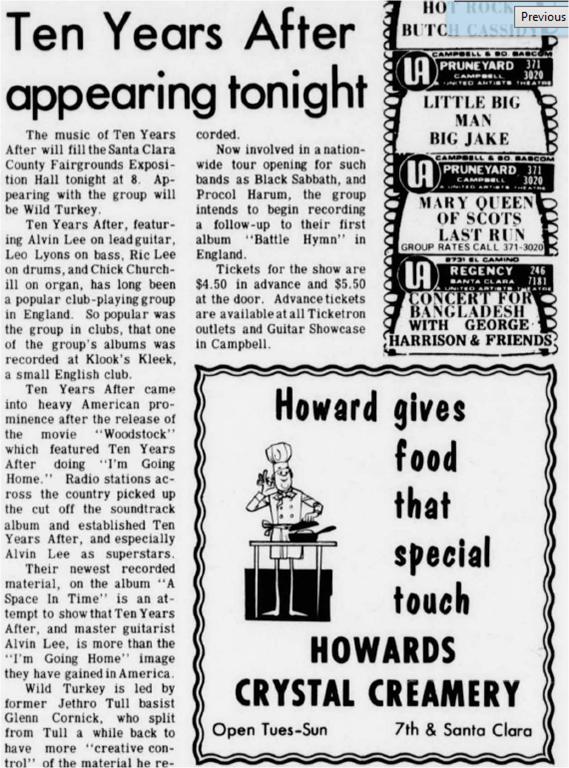

Mirror – January 1, 1972

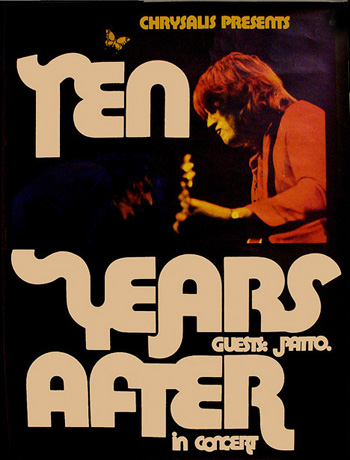

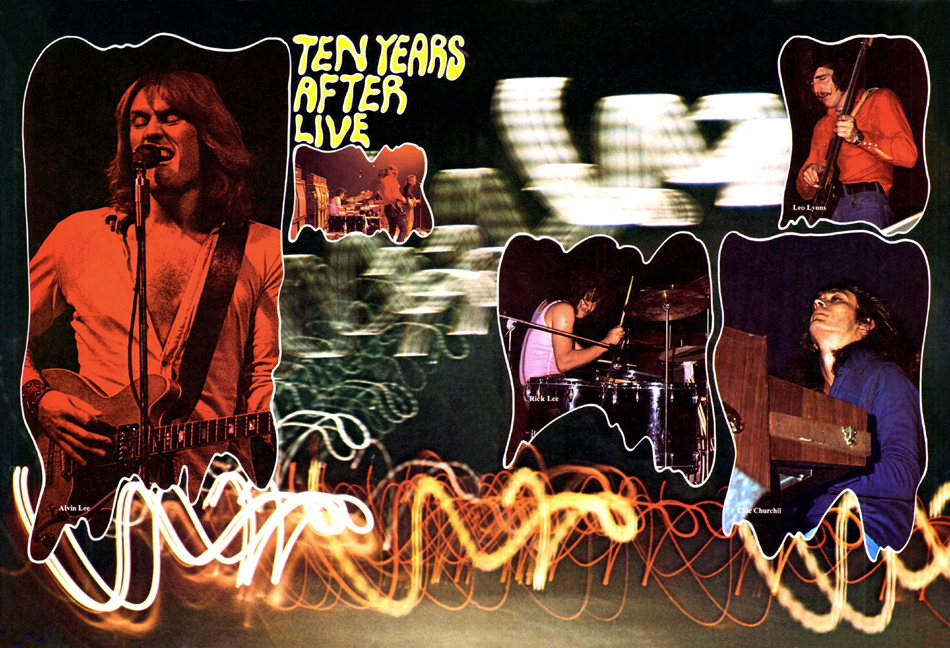

Ten Years

After have been awarded

their first gold disc, for

sales worth in excess of

$1,000,000 for their album,

“A Space In Time”. The group

will make its first tour of

the British University

Circuit since 1969 this

month. The dates are:

Reading January 8th,

Birmingham 13th,

Sheffield 14th,

Lancaster 15th,

Cardiff 19th,

Liverpool 21st,

Leeds 22nd,

Brighton 25th,

Nottingham 27th,

Salford 28th, and

Lancaster 29th.

TYA will be supported by

Jude, a new group formed by

ex-Procol Harum guitarist

Robin Trower and former

Jethro Tull drummer Chris

Bunker, on the dates at

Cardiff, Brighton and

Nottingham. At Sheffield,

Salford and Lancaster,

Supertramp will be the

supporting act.

|

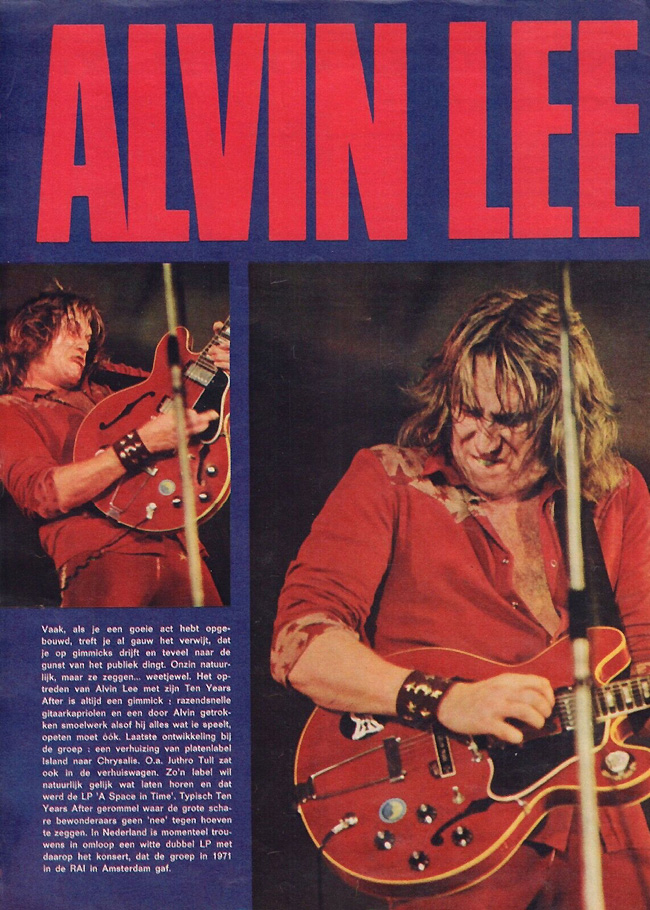

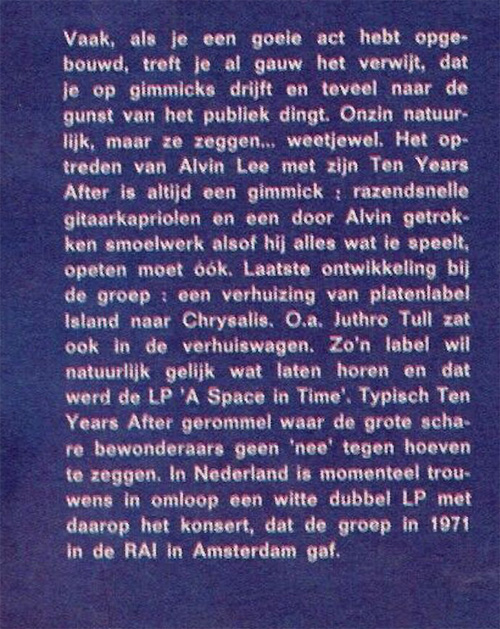

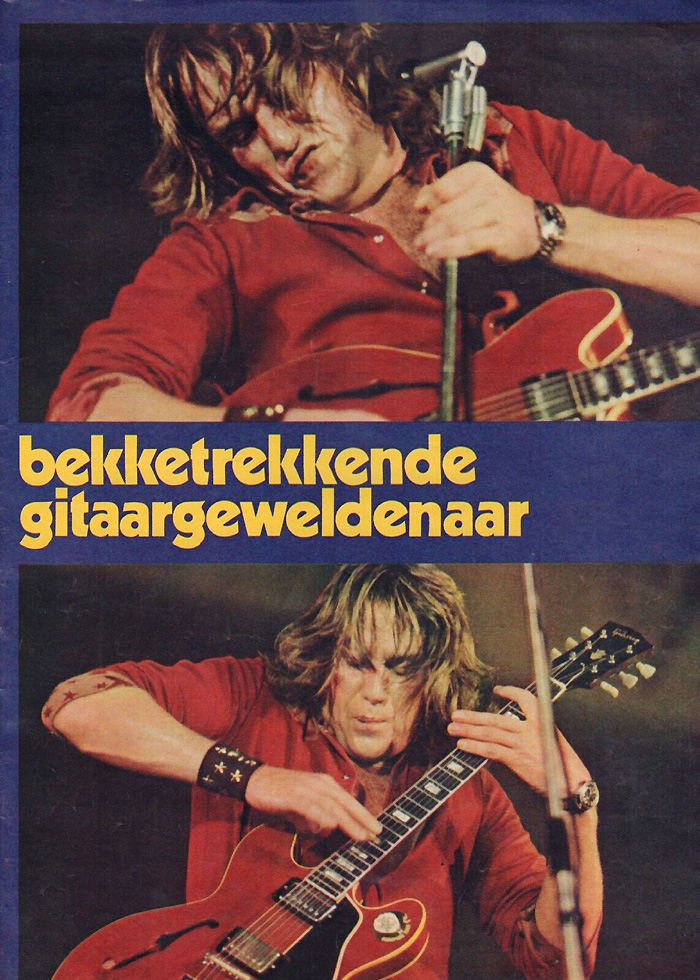

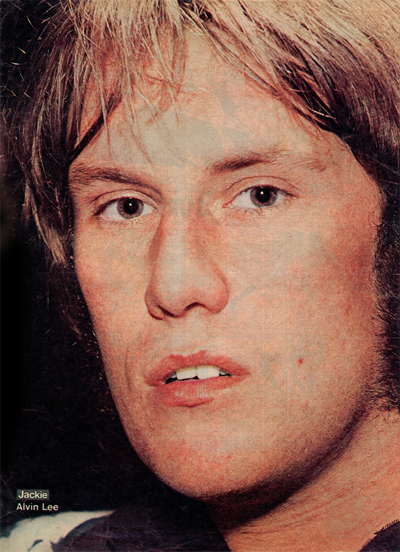

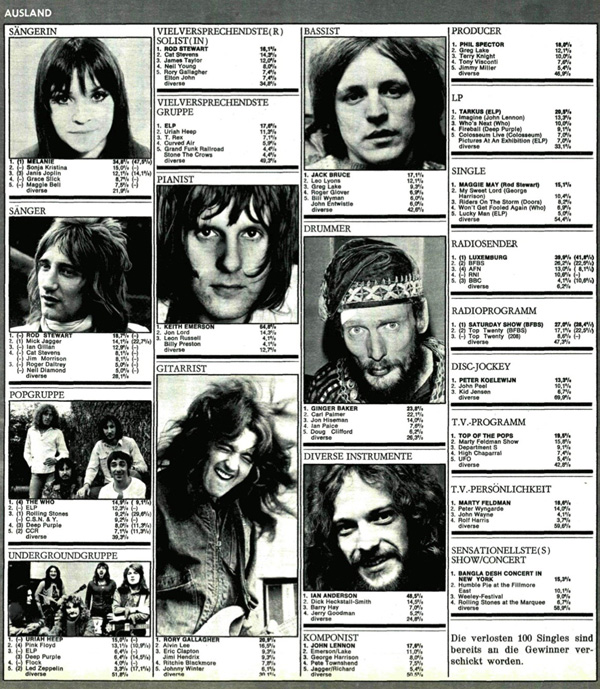

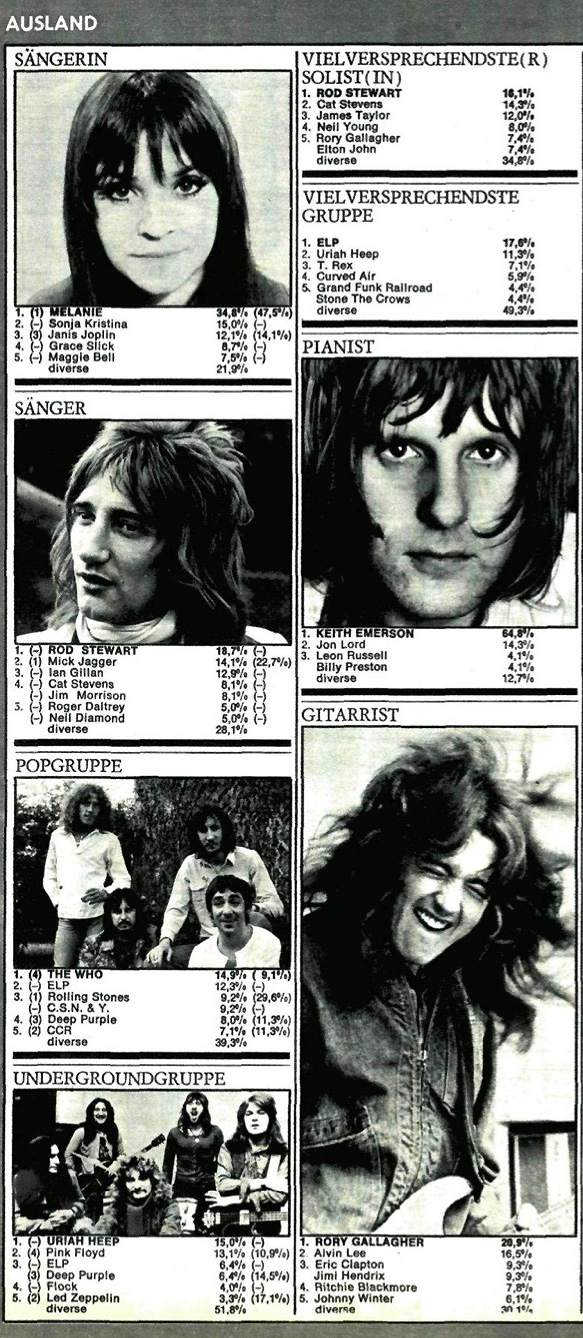

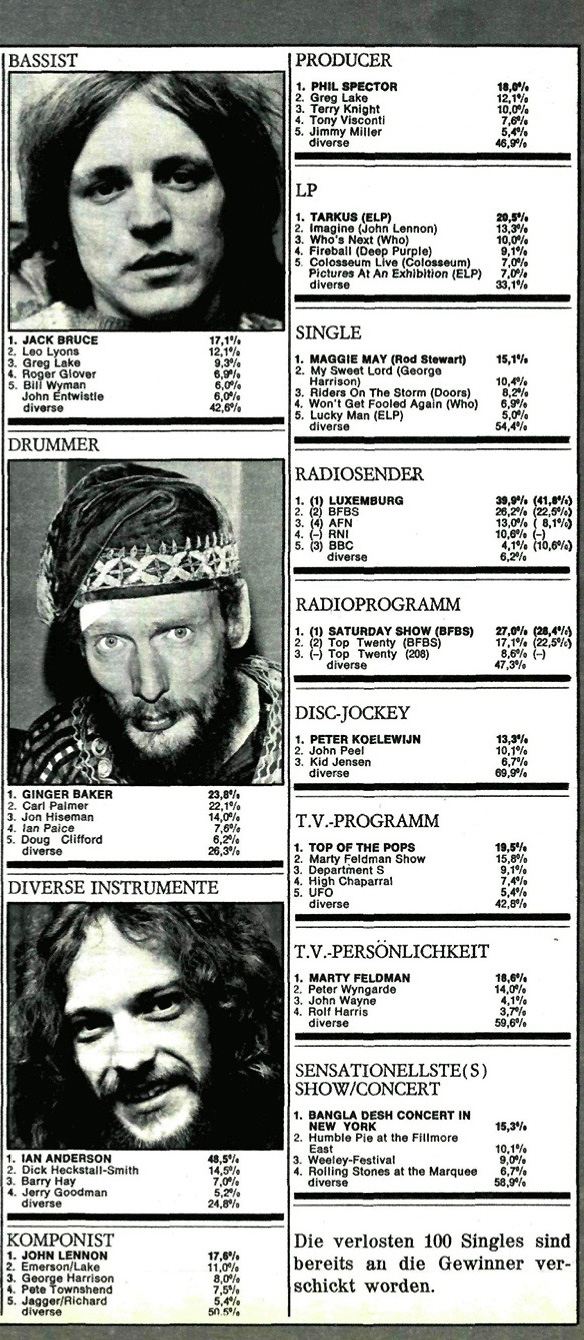

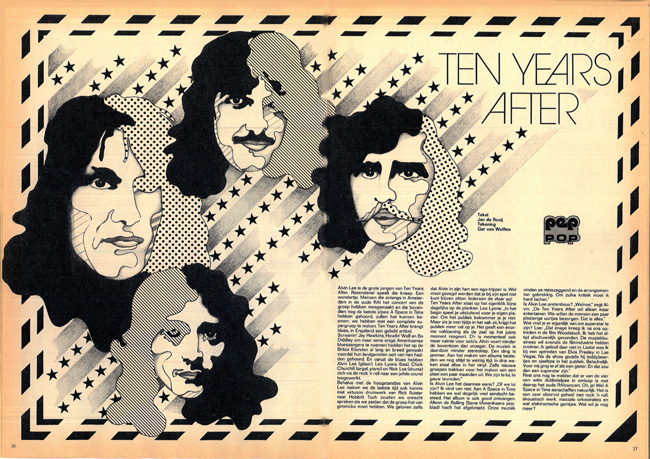

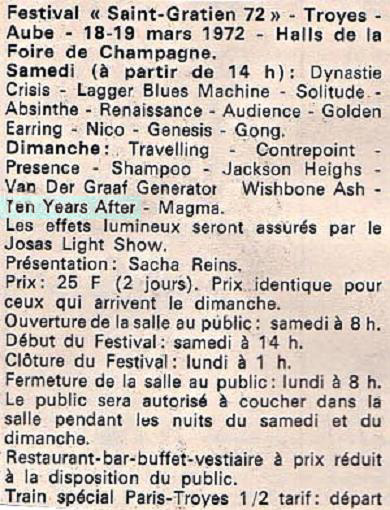

January 1972 - Muziek

Parade magazine

|

29

January 1972

|

|

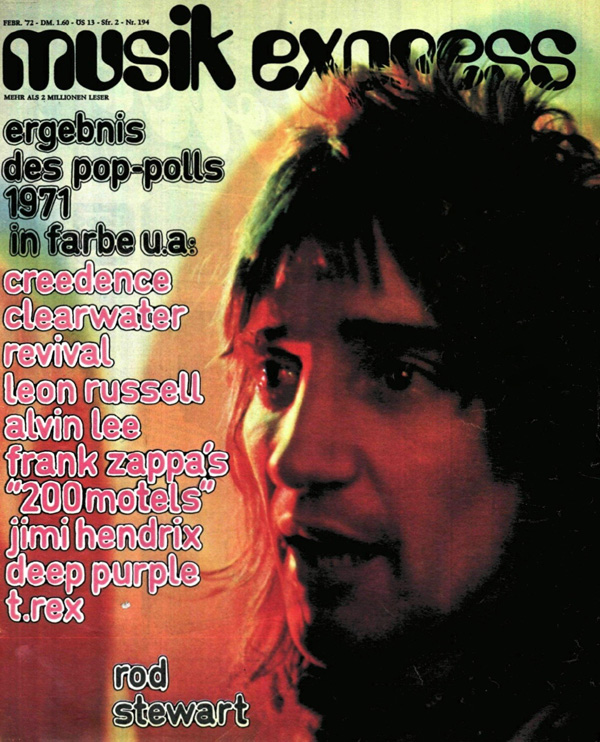

February 1972 -

Musik Express magazine

|

February 1972

“Alvin Lee

and Ten Years After did a tour

of Scandinavia with us

supporting (Patto). On the first

night we played an absolute

perfect set, and not one person

applauded. NOT ONE!

Then Ten

Years After come on, they hadn’t

played for six months. Ric Lee,

their drummer was so rusty, it

was unbelievable. It was like

Sweep playing the drums, with

Sooty on the magic organ! And

the audience went crazy. It made

me wonder, what it was all

about…certainly not about going

on and playing well. Anyway,

Alvin Lee couldn’t believe how

sensational and extraordinary

Ollie Halsall, our guitarist

was. He’d never heard him

before, and he absolutely

flipped. So he got a Revox tape

recorder, and recorded every

single Patto gig on the tour.

Alvin even used to travel from

gig to gig in our van. He just

wanted to be with Ollie”.

From John Halsey - Patto’s drummer

24 February 1972 - Stockholm,

Sweden

3 March 1972 - Berlin, Germany

|

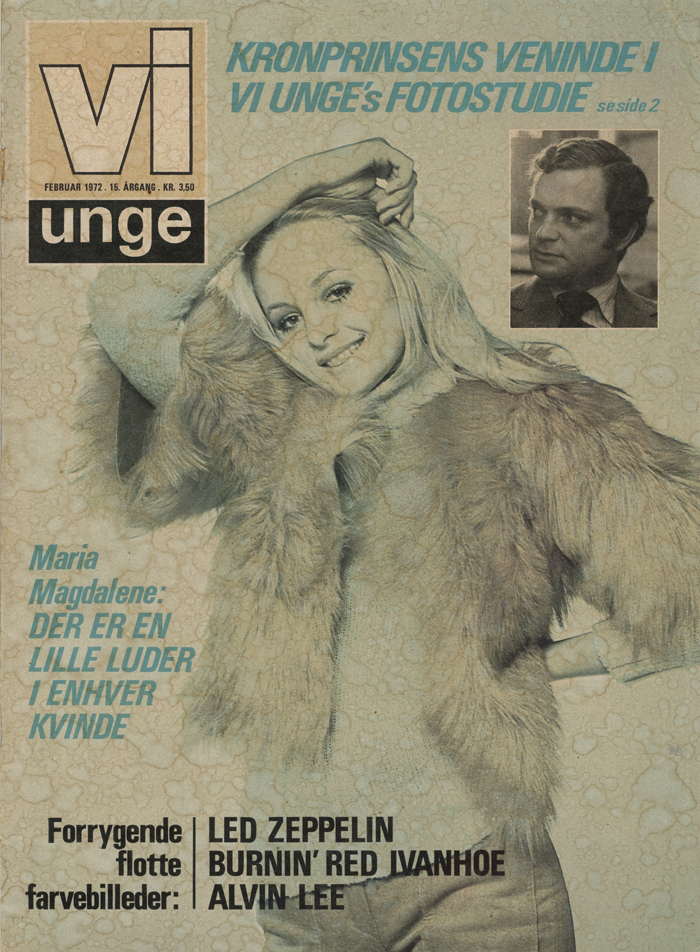

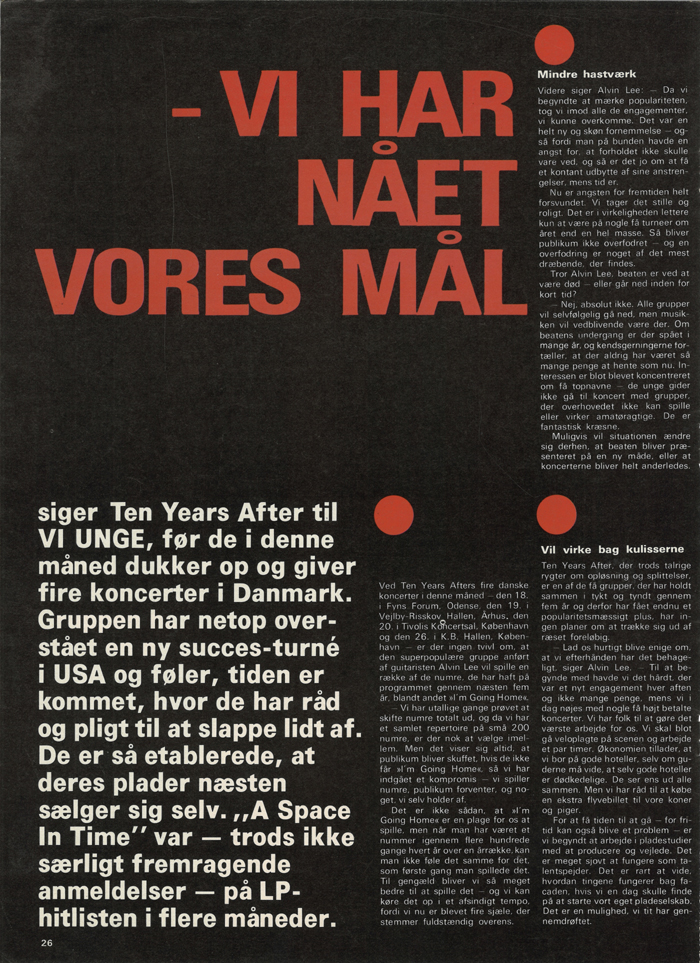

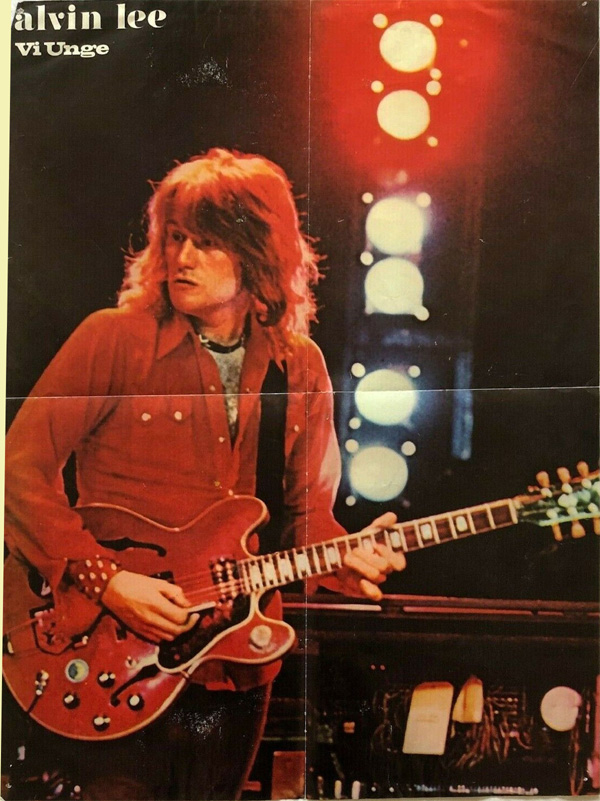

Danish

Magazine "vi unge" February

1972

Front

Page

Page 26

Page 27

Poster,

Danish Magazine "vi unge"

|

|

|

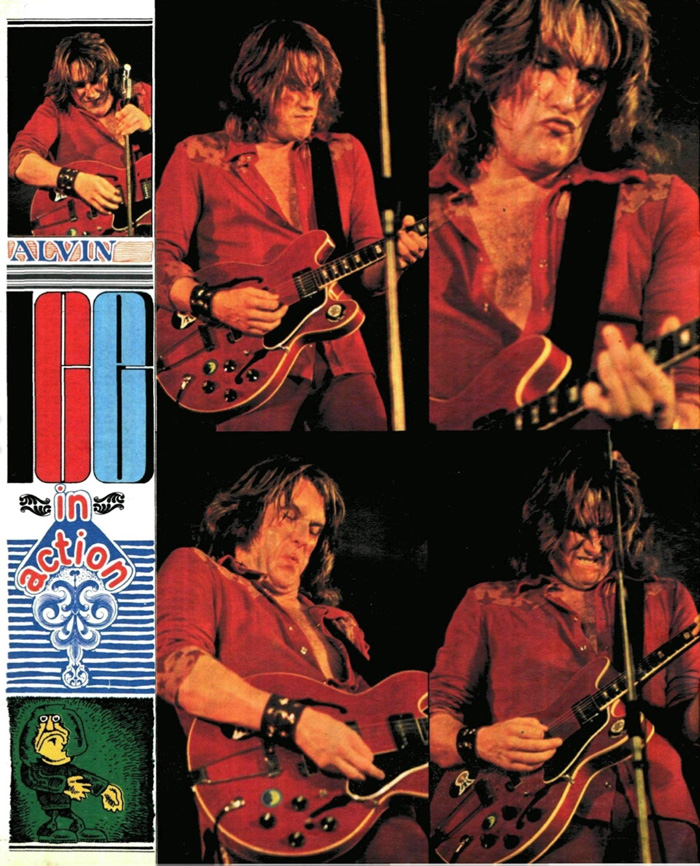

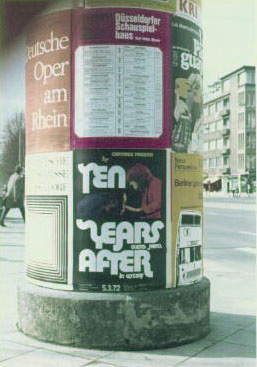

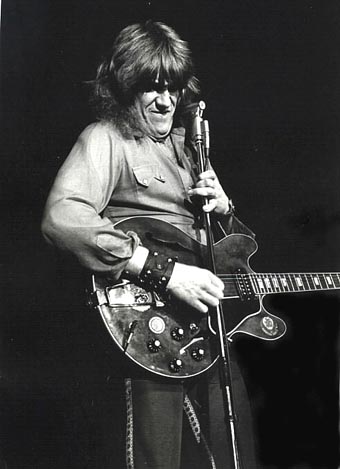

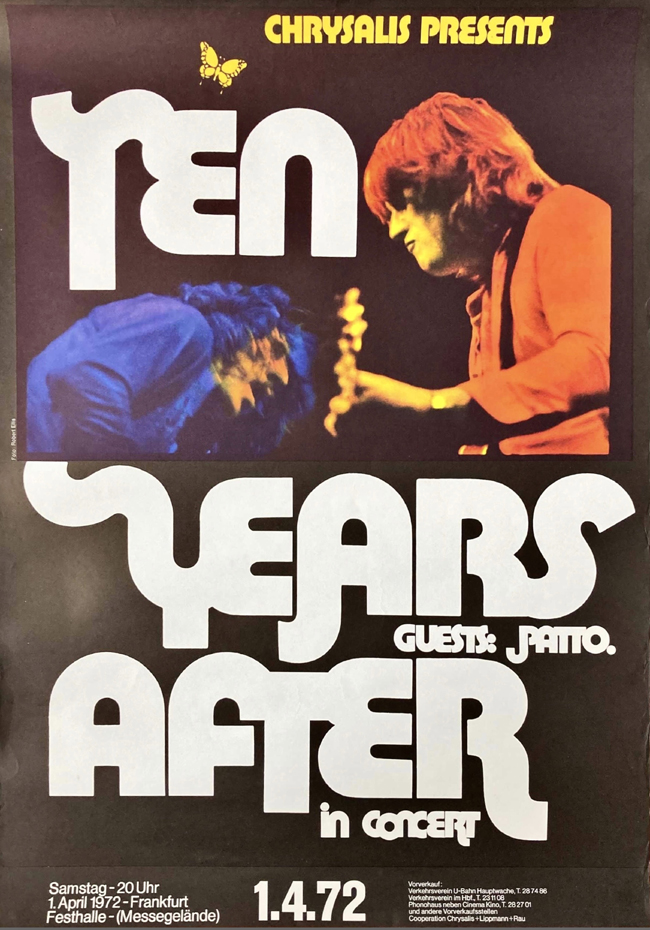

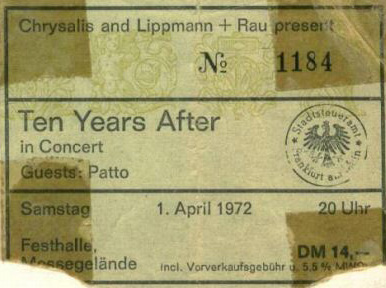

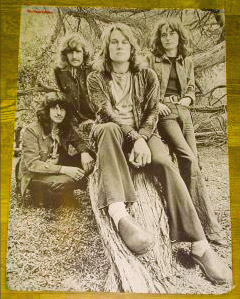

TEN YEARS AFTER

in Düsseldorf, Germany

5.3.1972

Photos

taken by

Hans

Hübner

Courtesy of

B & D

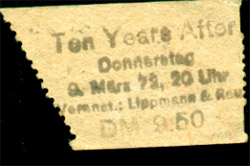

9.

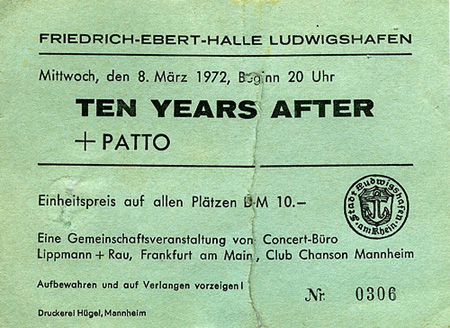

März 1972

Münster

Brigitte's

original ticket

DM 9,50

|

|

|

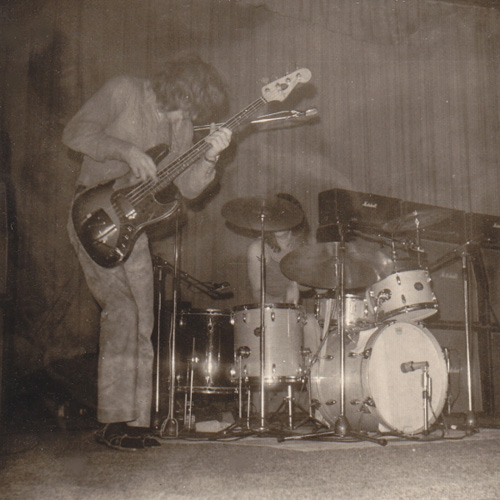

The following

photos were taken by Hans Hübner - 5 March 1972 at

Philipshalle Düsseldorf

Photographer:

Hans Hübner

|

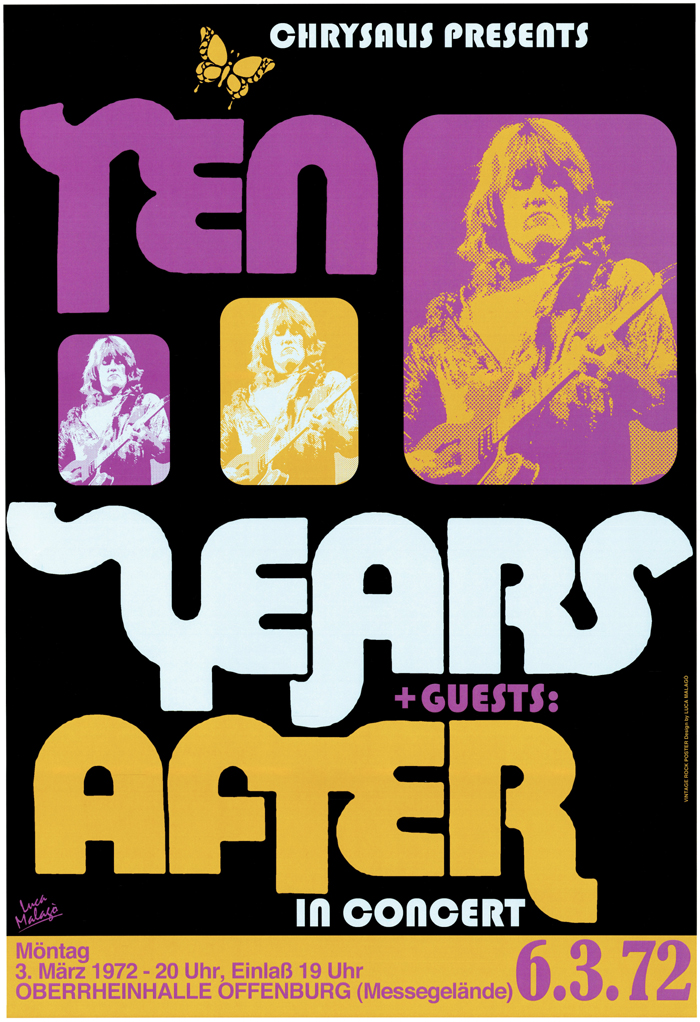

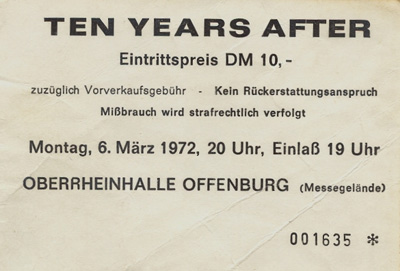

March 6, 1972 -

Offenburg, Oberrheinhalle,

Germany

Tribute

Concert Poster by Luca Malago

from Italy

6 March 1972 - Offenburg

|

|

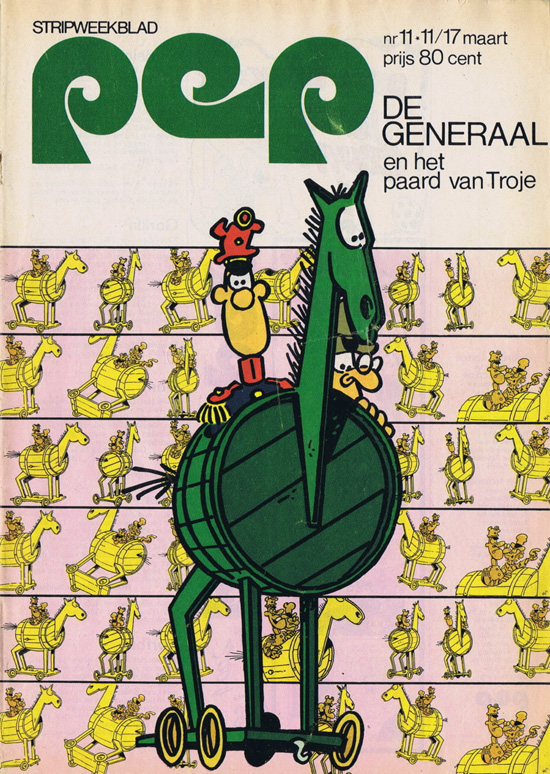

11 March, 1972 -

pep Magazine Cover, Holland

|

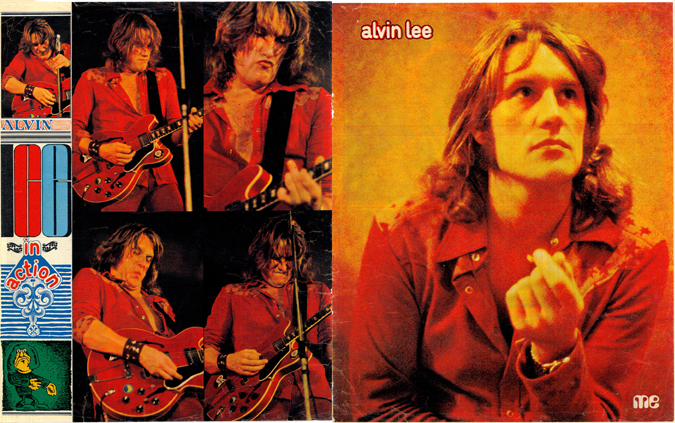

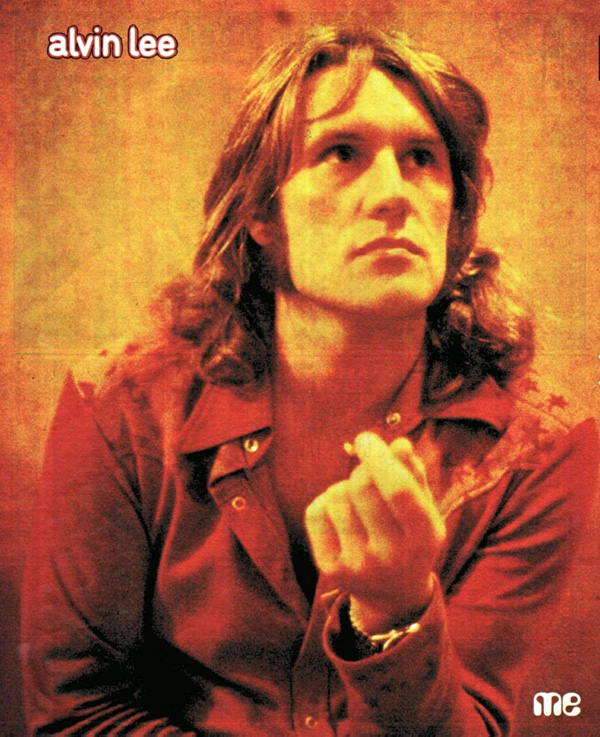

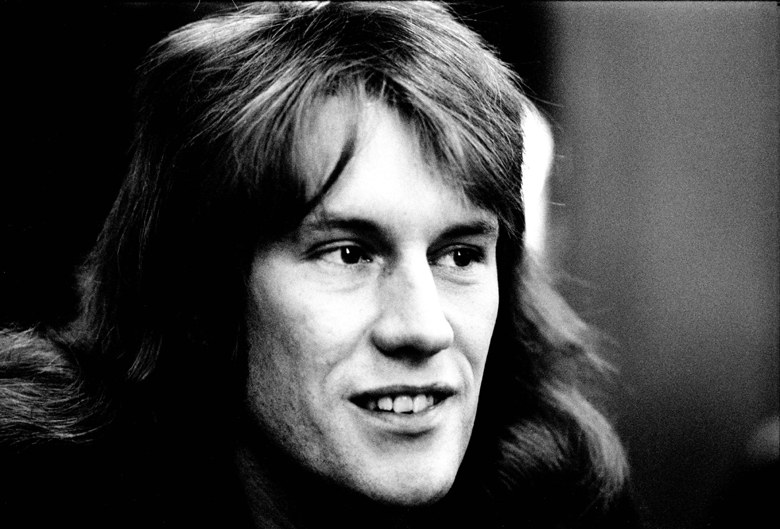

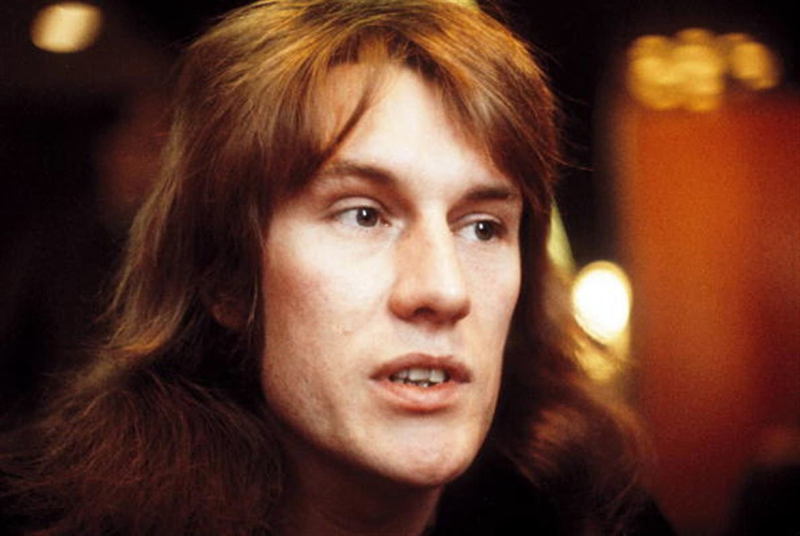

March 1972 - Alvin Lee

Portraits by Gijsbert Hanekroot - Netherlands

https://gijsberthanekroot.com/

- licensed from Alamy -

24 March 1972 - Ahoy

Hall, Rotterdam, The Netherlands

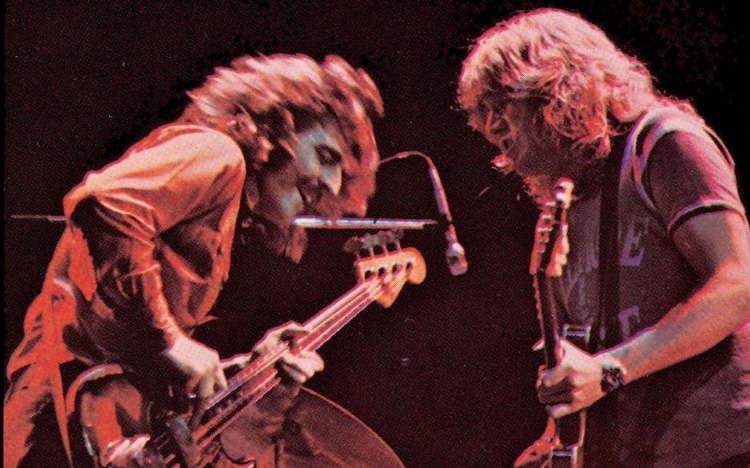

Leo Lyons & Alvin Lee

Photographer: Frans Verpoorten

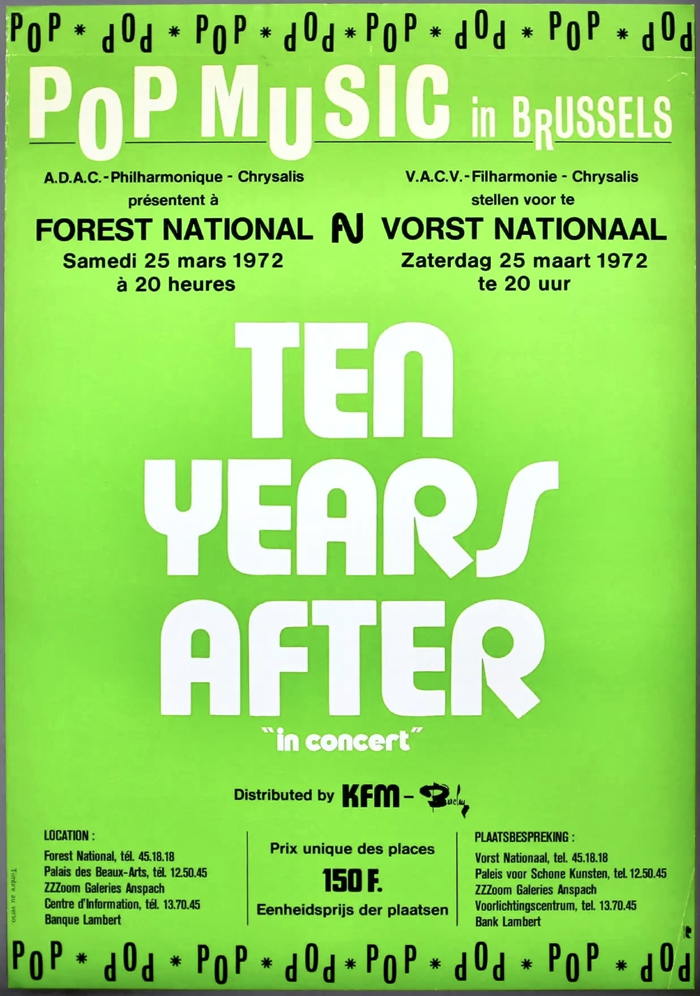

25 March 1972 -

Forest National, Brussels

Photographer: Jean-Yves Legras

Photographer: Claude Gassian

|

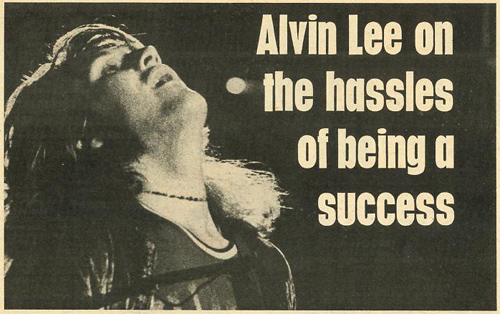

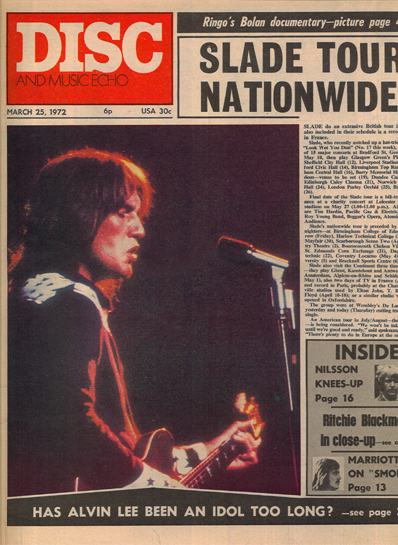

DISC

- March 25, 1972

“Alvin Lee on the Hassles of Being a Success”

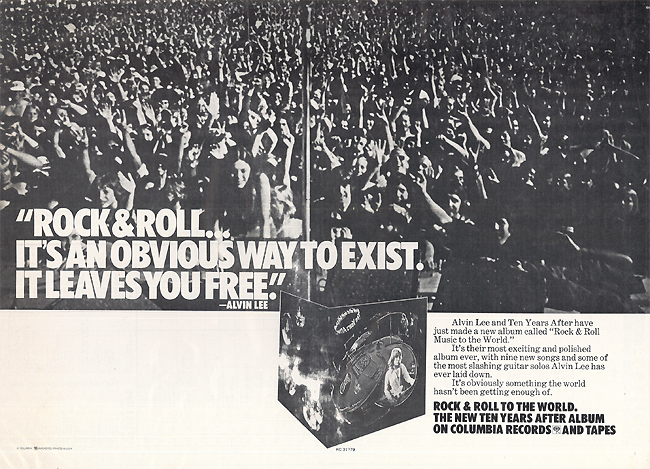

Alvin Lee is currently suffering from a surfeit of

everything. He’s had too much touring, too much hype,

too much idolatry. Nowadays the band can’t play without

being drowned by screaming or a constant barrage of blue

flash bulbs from photographers. They’re hounded at

airports and their records are bootlegged.

“As a band we were always thinking, perhaps we were

being successful and achieving something, but this is

the first year we’ve felt we’ve actually done it to some

degree. Before we were still kind of struggling to

control what we were doing, and now it’s settled down.

Tours come easily; the music changes, it’s almost boring

because nobody’s struggling any more. “I used to enjoy

the days when we’d get into the van together and sit in

it for five hours, our heads were much more together

then. Now there’s no hassle and you have a clockwork

schedule to follow, and a tour is run like a

campaign. It completely does away with that feeling of

companionship.”

Alvin is talking at his large Berkshire home. It is

homely and comfortable, with lots of bric-a-brac

gathered on tours. One room is devoted to his

photography and filming, a passionate hobby, which seems

to be fast overtaking the music, with a screen that

pulls down from the ceiling, and lots of big cushions

sprawled on the floor for happy viewing.

I Want To Make A Film

He runs through some excellent slides he’s taken in

America, France and here and there. He undoubtedly has

photographic talent, and is still very proud of the

article a photographic magazine did on him. We also

listen to some tapes of numbers for the next album,

which the band recorded in France recently, using the

“Rolling Stones” mobile unit. They have captured a raw,

driving bite not often heard offstage, with some

beautiful rock and blues numbers. They hired a chateau

to record in and used the vast marble hall so the drums

have a metallic bounce, and the organ echoes off into

the distance. Alvin was amazed at how much was due to

the unit, and how much to its psychological effect.

“Another drag about being successful,” says Alvin, “is

having to record out of the country to avoid tax. I wish

it would all be logical and straightforward, but instead

you get more and more into sympathy with Ray Davies

singing about the taxman taking all his dough. “It’s

unfair anyway because you’ve got ten years maximum in

this job, unless you want to go on and do cabaret work,

and there’s no way I’m going to be doing that. I want to

get into producing and recording; I want to make a film.

There’s so many things I want to do, it’s like standing

at a multi-crossroads.” Before we go any further, let it

be stressed, that this doesn’t in any way mean Ten Years

After will split. A group that has been together for as

long, and through as much as they have, doesn’t just

cave in overnight. Alvin is merely taking stock of his

thoughts; pausing before starting their thirteenth tour

of America. Since the hoo-hah following Woodstock, the

posters, the superstar treatment that Alvin got, which

he didn’t want, he’s obviously been doing a lot of

thinking, which has left him feeling rather wistful and

nostalgic for the pre-success days.

“We just wanted musical success really, the money is

great when you earn it, it allows you to put things back

into what you’re doing. Before we were just starving to

do well, we were so hell-bent on getting through, we

would work every night we could. When we did make it, we

had so much work coming in, we were on our knees, and

not daring to turn any of it down.”

“You see, we need to reach beyond our capabilities, and

now we come to the point where, are we best to reach a

bit further, or are we best to play the things we’re

doing well? We’re going to try and do some stock old

blues things, and see how that comes out, integrated

with other live things. The band isn’t the kind of band

that can just play in a studio. “The Beatles reached out

in the studio, and didn’t play live at all, and a lot of

bands are doing more studio than live things now, but

we’ve always been more of a live band, and you get a

feedback from an audience, which keeps you in touch, and

stops you going out on a limb. “But concerts, in some

places become more and more difficult. In Germany

recently, there were fifty photographers out in front

with flash bulbs going the whole time. It was terrible

for us, and terrible for the audience. I stopped playing

and got somebody to come onstage and tell them to stop

in German, but they all started up again three minutes

later. And once you begin to notice the hassles, it’s a

psychological thing, and it gets worse, like at Madison

Square Gardens, about two percent kept quiet.

English Tours Are Fantastic

“English tours are fantastic because they just sit and

listen, we want to do more in England, but the

commercial aspects mean you have to play the bigger

places, abroad as well, and of course the places where

the money is, there’s thousands of people pushing and

shoving and screaming, and you feel like a circus

freak.” Alvin now realises the need for him to get into

other things for relaxation, and diversification,

otherwise his music will suffer. “I need to diversify my

interest, I’m so wrapped up in music, I just get

technically involved and bogged down. The music I enjoy

playing now on my own is virtually Music. I need a fresh

outlook, something I can get into.”

Alvin has wanted to make a film for some time. He wanted

to take a camera and sound crew on the road with the

band some years back, and make a film about touring, but

then “200 Motels” came out, and said more or less

everything he wanted to. Alvin also wants to produce a

group, although he realises the irony of the situation,

as he himself is terribly anti-producers.

“I would never use one because I believe a true musician

is the only person to produce the music on record. Lots

of producers will say, “Oh, we’ll make that bass a bit

more like James Brown.” But my ideals about music seem

to be less and less important.

But to produce a group properly, I must be completely

into their music, and respect them.”

|

Alvin also despairs of the music that is selling in

these days. Ten Years After struggled for years unheard,

but playing the music they loved, and believed in. “But

now, you get bands playing so-called progressive things

because it’s the thing to play, and it’s gone very

shallow. I get sad when I hear all this middle of the

road stuff too, because it will mean that everything we

struggled for musically, over the past four years,

everything the under-ground brought over-ground, will

slip away and mean nothing, and more serious music won’t

have got a hold.”

Alvin also wants to do some more electronic music, which

he experiments with endlessly at home. He won’t use a

Moog, because he reckons that’s cheating, but fiddles

around with microphones on brass plates, and echo

effects. He’s got hours of tape, and is considering

giving it to somebody to put out if they’re interested.

!I mostly write things for the band, but what we put out

is an amalgamation of all of us, so for every one number

of mine we do, there’s eight the others haven’t liked,

that I’ve still got on tape. I’m not saying they’re

fantastic, but they’re a lot better than some things

I’ve heard that people have put out.”

Article written by Caroline Boucher

|

|

|

|

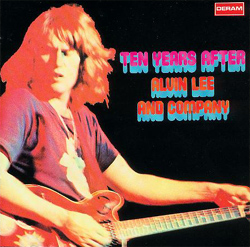

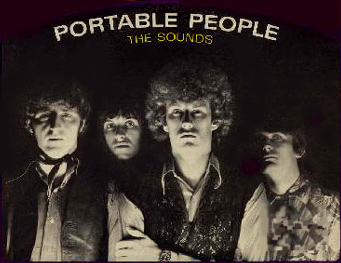

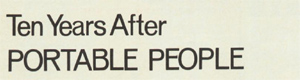

Ten Years After - Alvin Lee & Company (Deram

Records)

This LP, is a compilation of previously unreleased

material recorded prior to their label switch, (To

Chryalis Records) would

seem to be comprised of mainly throw-away cuts which is

definitely not the case. The material is easily as

exciting and diverse as that exhibited on their “Space

In Time” LP. (1971 – Columbia Records)

Alvin Lee again establishes that he is a consummate

guitarist, his licks irresistibly insistent. Check out –

“The Sounds” – “Boogie On” and “Portable People”.

|

New

Musical Express April 1, 1972 |

|

Ten Years After –

"Alvin Lee & Company" 1972

This is a

collection of songs that didn’t make it onto the

studio albums during the 1967-1969 period. The

original album features six tracks, the last one being

a mini-jam-session called, “Boogie On”, which uses up

as much running time as the other five combined. The

jam evolves around a simple riff, that’s played over

and over and from time to time being interrupted by

Chick Churchill’s organ, Ric Lee’s drums, Leo Lyon’s

bass and Alvin Lee’s guitar solos, that feature all of

the usual aural gimmicks. However, the first five

songs on the first side are a totally different

matter. Plain old boogie-woogie songs, represented by,

“Rock Your Mama” and “Hold Me Tight”. Then there’s

some old blues with the Robert Johnson classic,

“Standing At The Crossroads”, then a simple sounding

bluegrass shuffle called, “Portable People”. It’s only

“The Sounds” that comes across as an “experimental”

piece, complete with the obligatory synth effects with

a grim and desperate mood.

These

out-takes all fit into the criteria of “Good but not

Perfect” category, as each one of them shows distinct

flaws, which make it understandable exactly why they

never made it onto the official studio albums in the

first place. They come across as exactly what they

are, generic, underdeveloped and inferior to other

similar ones. The reason being, these tracks were

never intended to be released in the first place, the

Decca Record Company high jacked

Ten Years

After’s unfinished work, when the band decided

to change record companies, and that’s how this

release came about. To cash in on the bands current

success.

By Gene

Herbert CA.

|

|

Ten Years After – “Alvin Lee and Company” - 1972

This originally surfaced as a six-track retrospective

in 1972, after the band left Decca for Chrysalis. It

now includes three extra cuts, the seven-minute blues

B-side, “Spider In My Web”, and the mono-only single

edits of two of their most famous tracks, “Hear Me

Calling” and “I’m Going Home”.

The original album was dominated by the fifteen-minute

“Stonedhenge” out-take, “Boogie On”, which is exactly

the way it sounds. The 1968 export single “Rock Your

Mama” and “Hold Me Tight” are in a similar vein, while

the live “Crossroads” isn’t very exciting.

More worthwhile are the brooding “The Sounds”, which

opens the CD,

and the 1968 A-side “Portable People”, which belongs in

the same distinguished company as Canned Heat singles like

“On The Road Again”.

|

|

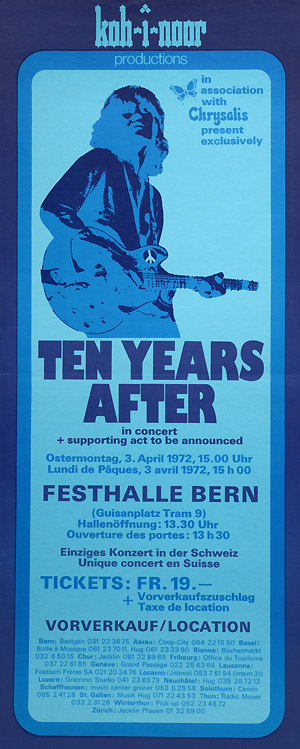

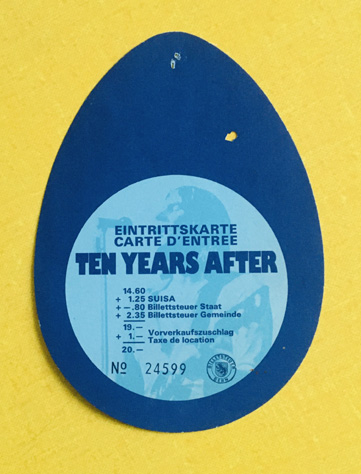

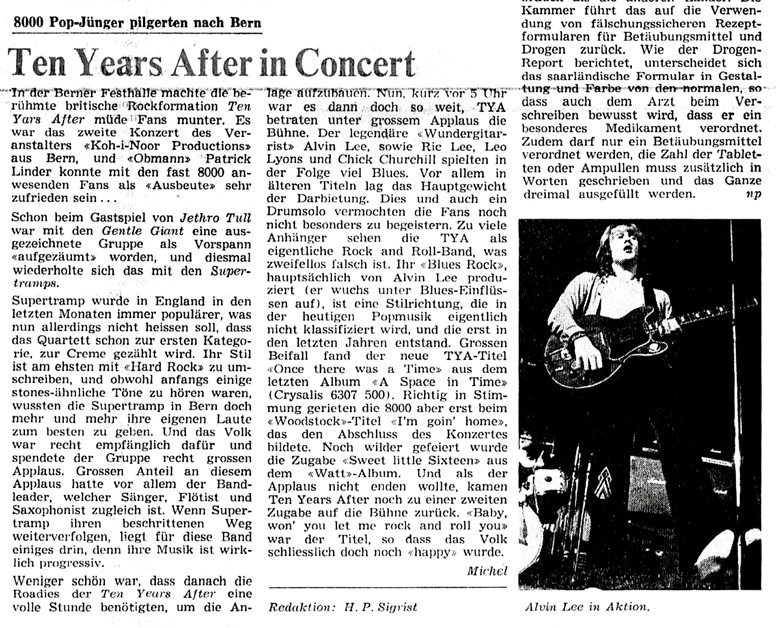

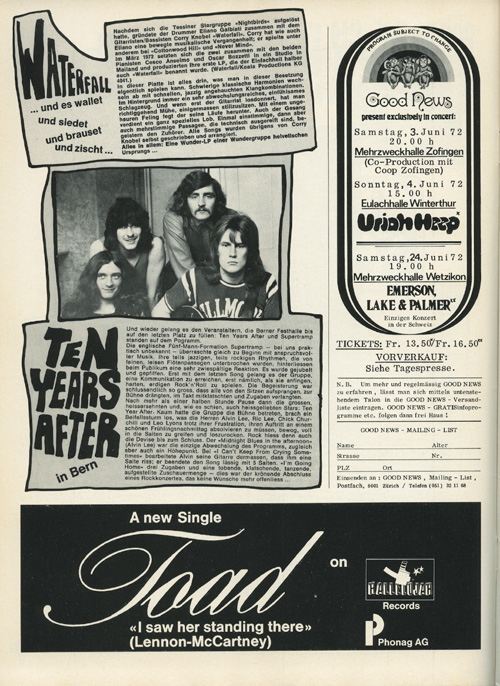

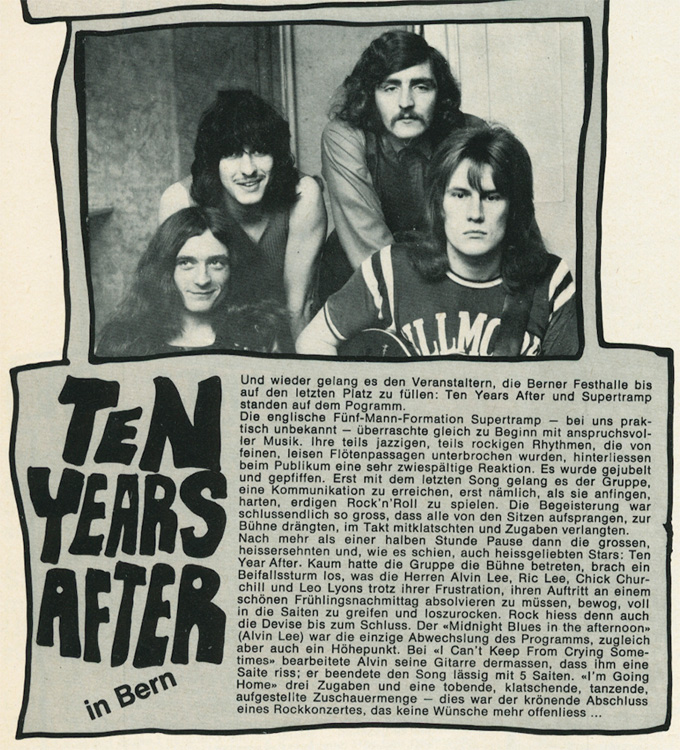

1972, April 3

Bern, Switzerland

Many thanks to Christoph

Müller for his contributions |

|

|

|

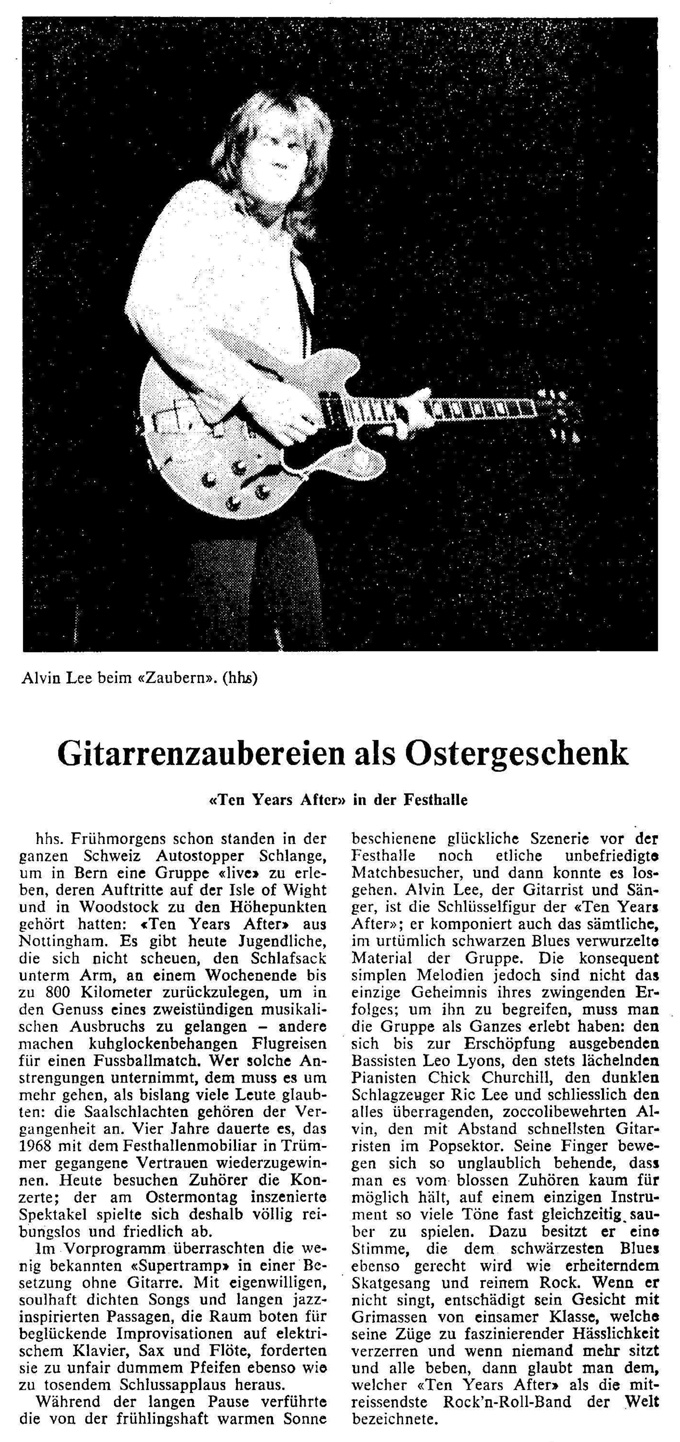

April 5, 1972 - Der Bund - Concert Review

Ten Years After in der

Festhalle Bern, Ostermontag 3. April

"Der Bund", 5. April

1972

April 6, 1972 -

Concert Review - "Thuner Tagblatt" newspaper

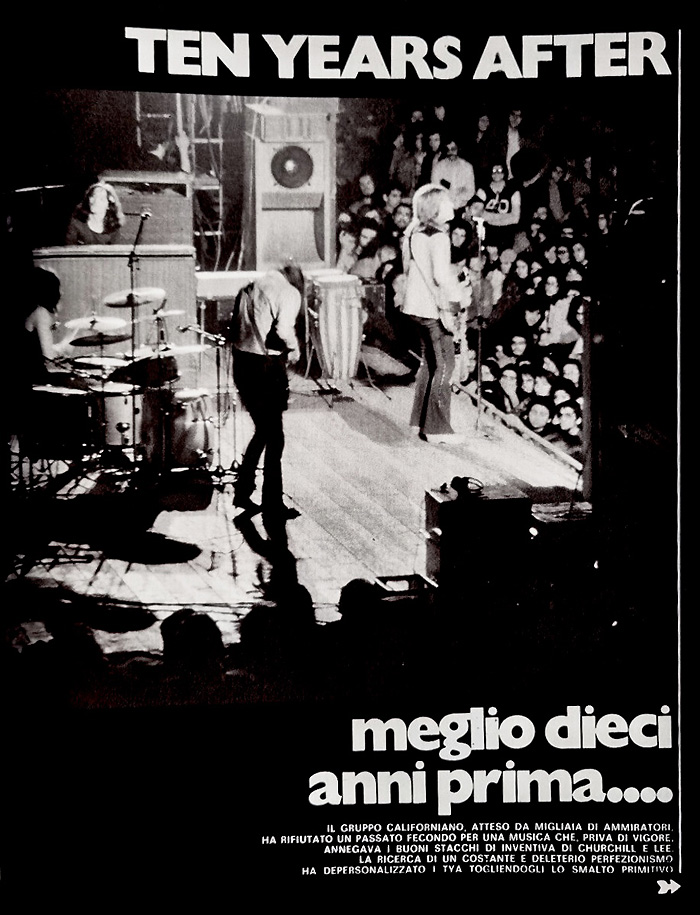

16 April 1972 -

ciao2001

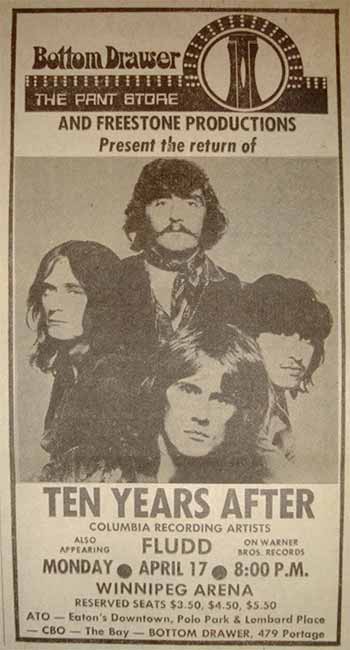

April 17 - Winnipeg Arena

|

|

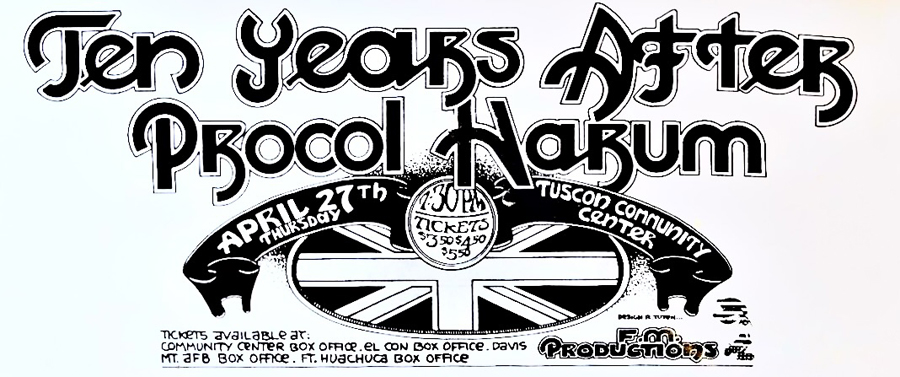

Ten Years After with Procol Harum

|

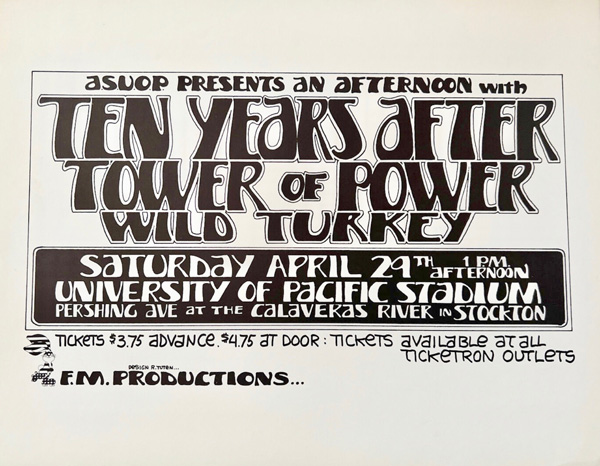

April 27 -

Tucson Community Center - Advertisement

April 28, 1972 (our thanks to Alessandro B.)

April 29, 1972

- Concert Review - "Die Tat" newspaper

Ten Years After in

concert,

April 29, 1972

at the University of the Pacific -

Amos Alonzo Stagg Memorial Stadium, which is a

Stockton, California Landmark. It first opened in 1950 and

overnight it became the city’s entertainment centre. The

Stagg Stadium really was the centrepiece of the Stockton

Campus, because it hosted so many big sports and concert

events. A lot of our alumni have a lot of fond memories of

events that took place there. When the rock group Ten

Years After performed at the stadium, the opening bands

were, Wild Turkey and the Tower of Power. On May 5, 1972

the rock band Chicago also performed at the stadium. The

Ten Years After Set List, is as follows:

- One Of These

Days

- Once There Was

A Time

- Good Morning

Little School Girl

- Hobbit

- Slow Blues In C

- Classical Thing

- Scat Thing

- I Can’t Keep

From Crying Sometimes

- I’m Going Home

- Choo – Choo –

Moma

- Baby Won’t You

Let Me Rock and Roll You

- Sweet Little

Sixteen

13 Roll Over Beethoven |

|

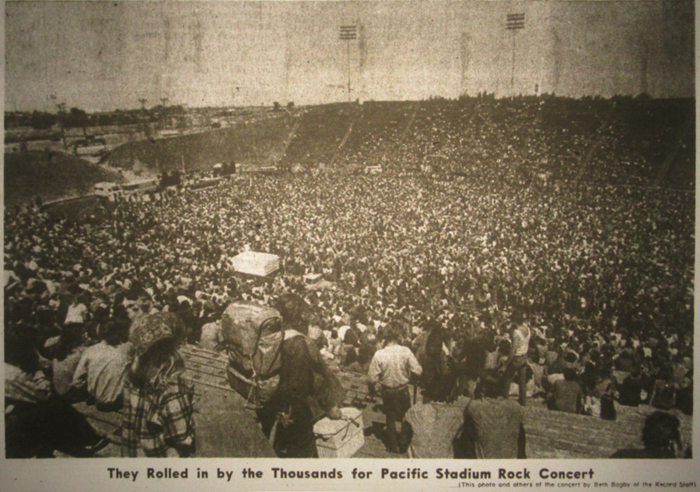

All was not

peaceful at this concert. Garry Lemmons, a nineteen year

old Madesto, California cannery worker, was killed and

another man wounded from a “wild gun shot” during an

altercation at the Pacific Memorial Stadium Concert that

featured England’s Ten Years After, the Bay Area’s own

Tower of Power and Ex-Jethro Tull members who formed Wild

Turkey.

This and the fact

that three men suffered strychnine poisoning at a Chicago

Transit Authority concert in 1972, which drew an estimated

20,000 people, brought an end to the concert run there.

Marc Corren recalled that on May 10, 1969 – the stadium

hosted the “Pacific Pop Festival” which featured: Santana,

Cold Blood, Elvin Bishop and Sons of Champin.

A very sad ending to something that started out so good

and positive.

The Audience Photo Above Was Taken By

Alvin Lee From The Band's Stage Perspective |

Record Mirror – April 29, 1972

Ten Years After –

Alvin Lee & Company (Deram)

This is an album,

that it must be pointed out, that Ten Years After are

totally against the release of, since moving on to another

record company (Columbia). Only six tracks are featured

here, including the mammoth “Boogie On” lasting over

fourteen minutes.

Heads around the

Lyceum might bob to a live performance like this, but on

record it’s pretty disastrous, with each member taking a

solo outing on their own instrument, then join in all

together for the big build up. The opening track “The

Sounds” has a fair vocal treatment and the most

interesting aspect of “Rock Your Mama” is the vocal

effect, that is alternating between each speaker in

stereo. But generally, it’s all pretty uninspiring.

Article by V.M |

POP

Magazine, May 1972

May 1972 - POP

Magazine, page 32 & 33

- Contribution by Marcel Aeby -

|

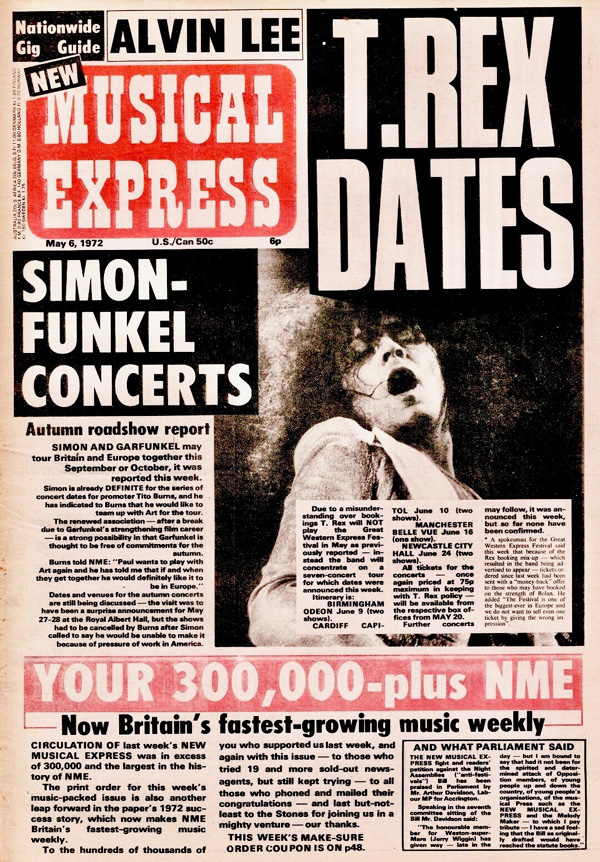

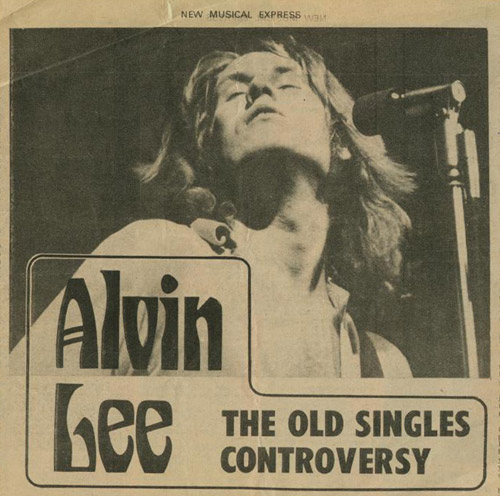

6 May, 1972

- New Musical Express

New Musical Express 6/5/1972

Question: To Get Into Another Completely Different Kettle

of Fish, As They Say.

What Do You Feel About Decca’s Release of Alvin Lee &

Company. I Know We Mentioned It Earlier, But We Didn’t

Completely Go Into It. Could You Tell Me About The

Material On That Particular Album?

Answer: It’s Left Over From Albums. It’s Left Over From

"Stoneheng". "B" Sides of Singles Which Were Put Out and

Were Nothing To Do With Us Anyway. You Can’t Tell Them

They Can’t, It’s Like Saying You Can’t Have Any Money –

"Well" – You Say, "If You Release A Single It’s The Record

Company Promotion For The Album. We Don’t Do "Top of the

Pops" and We Don’t Do Any Television. We Won’t Do Any

Promotion On It, So Please Yourself." This Album Is The

"B" Sides. One’s A Very Early Single We Did At The Same

Time We Recorded The First Album. It’s Not Too Bad:

Everybody’s Interested To See What Kind of Material We

Decided Not To Put On Our Albums For Them To Buy. But

Apart From That, They Didn’t Consult Us On What They Call

The Packaging of It. They Didn’t Say They Were Going To

Use A Photograph of Me and Call It "Alvin Lee and Company"

If They Had I Would Have Said No. What In Fact I Said Was,

"If They’re Going To Release An Album of Rubbish, Why

Don’t We Look Around Ourselves For Better Material To Use?

Question: Would You Object To Decca Releasing "The Best

Of…"?

Answer: You Can’t Object. We Have A Recording Contract

Which Everybody Has To Sign,

They Own The Songs. We Can’t Re-Record With Decca. They’ve

Got Thirty-Five Original Songs, Some of Which We Play

Completely Differently Now Because of Those Deals.

We

Signed When We Were A Bit Green. We Don’t Even Own The

Rights To Play The Stuff, Which Is Sad. But It’s

Irrelevent Really, Because We’re More Concerned In Doing

New Stuff. I Don’t Mind Albums Being Released, As Long As

People Know They’re Leftovers.

If

They Did Do A "Best Of" It Could Be Good and It Could Be

Bad. There’s Nothing We Could Do About It. The Thing Is,

We Could Do A Better One, But They Won’t Communicate With

Us About It.

Question: How Long Have You Been Together As A Band, and

How Long In The Present Form?

Answer: About Four and a Half Years. There’s No Reason For

The Band Not To Continue In Its Form For A Long, Long

Time. A Band As Old As We Are, Has A Problem In Keeping

Ourselves In Tune With The Music We Play. The More We

Play, The More Rehearsals We Do, Because The More Used We

Get To Hearing What We Do. When You’re Doing An Extensive

Tour – Playing Every Night – What You’re Doing Is

Performing Your Music To The Audience Every Night. After

Awhile, Although There Are Subtle Differences Which A

Musician Could Get Into, It Does Tend To Sound Much of a

Muchness. You Tend To Fall Into What You Did Last Night,

Because "That Sounded Good Enough". That’s The Kind of

Attitude That Comes In. It’s Really Hard Playing Every

Night and Travelling On A Plane.

You Don’t Have Much Time To Rehearse Or Think of New

Ideas. This Is Why We Work In Tours, Rather Than Just

Play. We Do A Tour For A Month, Play Every Night, Then

Throw New Ideas Around. If We Can Come Out With Three New

Numbers For The Next Tour, Well That’s Enough To Get Into.

We Record Every Night Ourselves. We Always Record

Ourselves Live, and We Listen Back To The New Numbers and

Make Changes.

Question: About Two Years Ago You Nearly Went To Russia,

But You Didn’t Go There,

Are You In The Future Planning To Do Iron Curtain

Concerts?

Answer: Well No. That’s One Thing That "Woodstock"

Stopped, Actually Because We Were Going To Play The Iron

Curtain Countries On A Basis of a Cultural Exchange.

"Woodstock"

Led Them To Believe It Would Be More A Rock ’n’ Roll

Concert Than A Cultural Exchange, Which In All Fairness,

It Probably Would. So I Don’t Think There’s Much

Possibility of That Happening Now. We Get Loads of Letters

Now From Iron Curtain Countries. They Can’t Buy Albums

There, They’re So Surpressed, Silly Things Like They Can’t

Buy A Ten Years After Album Or Anything. It Really Affects

These People and They Write and Say They’ll Exchange Their

Czechoslovakian Folk Records For Anything We Can Let Them

Have.

It’s Sad, Sad. Something Like Music, Man, You Should Be

Able To Go and Listen To Whatever You Want. Ideally, You

Should Be Able To Go Whereever You Want and Say Whatever

You Want. But It Does Seen Difficult In This Over

Populated World.

|

The Private Life of Alvin Lee

- by Simon Stable

New Musical Express May 6, 1972

Alvin Lee of Ten Years After seems to spend more time on tour

than on holiday, but recently before yet another American

tour, I managed to get to see him at his country home. After a

pleasant and enjoyable chat he played me a track he’d written

and recorded the night before, a number

he’s thinking of putting on the next album. It was

another of his fast foot-tapers with plenty of harmonica and

guitar panning from side to side. He told me he was planning

to call the song “Holy Shit”, though he did say he might be

forced to change the title and some of the words. I’ve known

Lee for about three years and, despite his success, I’ve

always found him to be an easy-to-get-on-with guy. He is, as

the following interview may show, an interesting and

intelligent person.

After your third album “Stonedhenge”, why did you change

producers? Why produce yourself?

Good question. Well, when we did our first album we were very

new to the whole recording situation, and our producer was

provided with the studio and we were told to appear at ten

o’clock in the morning and make an album. And it was out in

four days. We were very green. We just recorded all the

numbers we did on tape in the studio. I don’t think at the

time we even heard it until it came out. When it finally did

go out, we were quite disappointed, really, as the result

didn’t seem to have the dynamics of the record we had played

within the studio. And we realised this was down to the

recording techniques. The second album was live, so there was

nothing to do about that. Then we decided to produce

ourselves. Still, being rather green we used the same studios

that we’d been given. It’s a Decca album, so we used a Decca

studio. It only had a four-track machine. There were no

facilities for panning stereo, and what little bit of that we

did we had to have equipment specially made.

We had this little box made to pan across an

instrument, from one side to another. That’s the reason for

all the corny panning,

just one box with one knob on. It was just a matter of getting

into the format. Getting to know what it was all about. We

realised that rather than doing what somebody else suggested,

who wasn’t really interpreting our music the way we wanted it

interpreted, anyway, it would be best doing it ourselves. Even

if you make a mistake, I believe that your own mistakes are

better recorded than someone else’s. Ten Years After music is

quite personal to us as musicians, and I think it should be

recorded our way than the way a third party sees it. I believe

of all musicians , I find it hard to respect a musician who

uses a producer, because I think that if a musician knows what

he wants to put down, he should do it himself.

That’s where the art of recording comes in, to know how to

apply your music to the tape, to get the results in. We

haven’t, to my own personal satisfaction, done anything at all

incredible, but every album has had good bits, and we’ve

learned from them. So, hopefully, we are in control and will

make them better and better as we go along, which is the

logical progression anyway. I must be putting producers out of

business!

Do you feel your part in “Woodstock” helped your career as a

musician or not? I mean, it put you in the public eye, but did

you not find you were playing more and more request, and less

and less of the things you actually wanted to do?

Well, we never play request. We never play anything other than

what we want to do. However “Woodstock” did have considerable

effect. When we did “Woodstock” we didn’t realise it was going

to be such a big thing, just a festival which we had to arrive

at on time. It wasn’t until we got into a helicopter, and flew

in, that we realised what a big thing it was. Even then, we

weren’t to realise how much world attention it would get,

which it did. It was on national news in America and

everything, and that’s more than I expected, so the kind of

publicity we got from being in the “Woodstock” film initially,

like gave us a boost in popularity. A lot more

people had heard us, where as before “Woodstock” we were still

playing the concert halls and we were still selling enough

albums, we were doing really well. After “Woodstock”, well we

found that more people were coming to the concert halls, more

people were buying the album, but it was on the strength of

“Going Home”, which is a nasty situation. You can’t take

control of it. First, like, a lot of young kids were coming to

the concerts who weren’t particularly into what we were trying

to do, merely into us having been at “Woodstock”, and it was

more or less a kind a rock ‘n’ roll circus, which is what we’d

been trying to avoid up to then. And it got a bit out of hand,

and I did in fact regret having been in “Woodstock”…fearing it

was going too far out of hand, but we used the opportunity of

the press and that, doing Press articles to say that we wanted

people to get into the structures of the music, and listen to

what we were trying to do as well as rock ‘n’ roll.

EXHILARATED:

I explained, that we rock ‘n’ roll at the end, just to

have a good time. Roland Kirk does the same thing—plays all

his serious structures for two hours, then ends up laying on

the piano playing a twelve-bar. It’s a good way to finish off

a gig: gets

everything out of your system, and everyone can have a good

rave-up and go home feeling exhilarated, which is a good

thing. But I feel that if “Woodstock” had used “I Can’t Keep

From Crying”, it might have been a bit more helpful to us,

‘cos it would have spotlighted the more constructive stuff

we’re doing. But all in all, now that “Woodstock” has died

down, I don’t think it has made much difference. It might have

turned-on a younger audience, maybe they’re now into something

else. I find the straight pop, the entertainment side of

music, has a very select audience. It’s not something we get

involved in. Like singles, we don’t get involved in them,

because you have a hit single, then “Top Of The Pops”, it

doesn’t bring anything that progresses the band. Like a band

that’s nowhere can have a hit single, and suddenly start

getting a reasonable turn out for their concerts and probably

better contracts for their next single. But they’ve got to

keep on recording hit singles, and to do that there are people

that specialise in aiming hit singles at the mass market. It’s

a disgusting , soul-destroying kind of business to get into. I

believe the musician should record the sounds he likes and

wants to express, and a lot of it as far as we’re concerned is

left to chance.

When TYA took off it wasn’t because we aimed to write

music at the audience, it was just that people had

picked up on what we were doing, and the more we did it,

the more people got into it. That’s all it’s ever been

really.

When thinking of Ten Years After, one usually thinks of

Alvin Lee rather than the rest of the band. Do you ever

feel any resentment from the others? TYA is a co-op, we

all get paid the same; we all attempt to do the same

amount of work; we all tour the same, because I’m the

singer and the lead guitarist, it was quite on the cards

I should be singled out as the front man, because I

stand in the spotlight. It was intended originally, when

we started out, we hoped to make it four people on an

equal level. It was through nothing to do with ourselves

that this Alvin Lee business got picked out, we

didn’t encourage it.

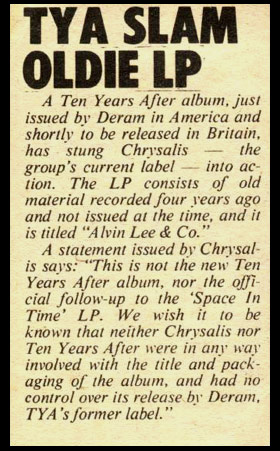

We had to disown this new Decca album they’re bringing

out of old tracks, because it’s got Alvin Lee and Co.,

and that’s the very thing we’ve been trying to avoid. We

talked about it when it happened and said, “look, this

looks like it’s going to happen, and there’s nothing

much we can do about it.” When people say Alvin Lee this

and that at concerts, I usually personify what they

either like or don’t like

about the band. It’s just how they refer to the band.

You yourself say that when one thinks of TYA, some

people do think of an Alvin Lee back-up band.

To our minds it isn’t. It’s not a thing to really get

concerned about ourselves, it’s irrelevant to what we’re

trying to do. It’s a kind a super-star role, which we’ve

never encouraged, it’s just a kind of misunderstanding. I

mean, I can explain myself completely to anyone who calls me

a super-star, but I know very well they don’t know me,

they’re just saying that without enough knowledge, so

there’s no answer to it. It’s a shame that everybody can’t

understand every musician that exists for the true fact of

what he’s trying to do. Eric Clapton is your number one

guitarist, and so many people adore Eric Clapton and hate

everyone else for no logical reason, it’s just the way

things go. You can’t control it, it’s just the way people

think.

Your last album “A Space In Time” didn’t do incredibly well in

England. Do you feel this had anything to do with the fact

that American copies were imported and on sale long before its

British release? Or was it that the album wasn’t up to

standard?

Well, I wouldn’t say up to standard, I think the standard as

far as we are concerned was better in some ways. The major

reason it didn’t do as well in your album charts was due to us

not releasing it at the right time in England. We were

pressured to get a release date with the new Columbia label in

the States, so we released it there first. It was three months

before it was released in Europe, and a lot of European sales

were lost because of the import shops buying it from the

States.

NO IMPORTS: That helped the sales in the USA, it was a

gold album in the States, the first one, so obviously it was

received there better than anything else we’d done. That’s the

reason I was given when I said “what’s happened to the last

album?” I think it’s true. Our next album is going to be

released on the same day world-wide, so every market that

sells it will be selling their own copies, not importing it

in.

What did you feel about your concert at the Colosseum. Was the

Sunday night better than the midnight, Saturday?

Oh yeah, The midnight show was a bit slow, the audience seemed

tired. Those things like having to wait an hour from the time

you got in, to when the first band played, always affect a

concert. That can be the difference between going down well

and having chairs thrown at you, whether the road managers and

equipment function well, and it all comes together in time or

not. If it doesn’t go well there’s nothing you can do except

get it together as quickly as possible. I wasn’t disappointed

with any of the concerts.To my mind there’s no good concert

hall in London. We didn’t play the Rainbow unfortunately, that

might have changed my mind. You see, we were

playing to four balconies at the Colosseum, an eighth of the

audience. With our spherical array of speakers and horns we

can hope to cover about a hundred degrees of sound, which is

about forty percent getting good sound. It’s just acoustic

problems and technical difficulties in projecting the sound

into the audience, which is always a problem where ever you

go.

UNFORTUNATE:

There will always be people getting bass boom, always

be people hearing too much guitar, too much vocal. I think

people who sit in the middle, about ten or fifteen rows back,

get a good sound and know what’s going on. It’s unfortunate

that someone standing at the back gets the sound blocked off

by people standing up in the front.

It’s Better At Festivals, in Fact?

Right, you’ve got no acoustic problems, and you’re in the open

air, which is always nice. There is a problem being in the

open air that is easy to overcome, you just have to use a lot

of power and a lot of speakers. It’s when you get sound

bouncing around halls, hitting the ceiling and bouncing back.

When you play loud, it’s a different case. You get good sound

drifting across an auditorium, reaching a listener up on an

acoustic level, but when you’ve got a lot of sound coming out

of the speakers, then suddenly the corners of the room, and

what the ceilings are made of, start affecting the sound.

These are the problems, more or less.

You’ve just been on an extensive European tour and you

frequently tour America and Japan. Which countries do you

prefer to play most and why?

Well, it changes, at the moment I really enjoy playing in

England. The last concert we did, you could hear a pin drop

all night long, and people really sat listening, getting into

what we were doing. When it came to like rock ‘n’ roll at the

end, they got into that and had a jive around, which is—as far

as the format of our concerts go—perfect . More recently than

that we did the colleges, which was like getting back to the

roots-razzle-bit after playing Madison Square Gardens and the

Philadelphia Spectrum. Twenty thousand people. Really it was

almost a shock. The first college we did was at Reading

University: it’s just a little wooden hall with about 1,300

people in it.

You go on stage and there’s none of this Ten Years After bit,

awoah! You just walked out and said hullo, and people were

sitting there and it was like getting back to the old club

bit, I really enjoyed it. I felt you had to really kind’ve

work; get things to work on stage. At a really big concert it

becomes a bit like a circus, often comparable to feeding lions

to the Christians at the Colosseum in Rome. You stir up so

much excitement: by the time the band goes on you sometimes

feel that what you play isn’t that important. That’s a wrong

feeling to take, but sometimes it occurs to you when you do a

lot of concerts. When you walk on stage and people cheer for

two minutes you feel flattered but are they going to listen to

what we are going to do? And half the while, they’re cheering

through the first three numbers as well. They’re just having a

good time, which is great, but I like people to listen to the

music. If you go down well I like to feel it’s been

earned—rather than just happened.

Are you going to do any festivals here?

I hope so. I want to see festivals continue myself, for more

reasons than one. I don’t know of any plans to do a festival,

but we’ll spend time in England after we’ve recorded the next

album. We’ve got possible dates for festivals, but nothing’s

been confirmed.

On your last album you added strings to your last track—are

you in fact thinking of adding horns on the next one?

Yeah, thinking of it. On an album we try and show where our

music is at, but for variety, we try and have a couple of

tracks to play around with, and we always find it nice to do a

track which is out of character so everybody says ‘Why Good

Lord This is Nothing Like Ten Years After!!!! So therefore, if you put a nice soft mellow un-Ten Years

After between two Hard TYA tracks, it adds to the overall

variety of the album. You don’t get this grind, grind, grind,

grind of some rock albums, because they’re all the same tempo

throughout. So for that reason alone, we really enjoyed doing

the strings on the last album.

It was just an experiment to see what we could do with

strings, and I’m really happy with it. It’s one of the best

string things there is. It had very little to do with TYA’s

music as people would think of it, but there again, music

doesn’t really mean that it’s just what people have picked up

through things like “Woodstock”, and variety is quite

important to us.

We’ve just been recording in the South of France. We hired a

big house there and the Rolling Stones’ mobile truck, and

whether we were influenced by being in the Rolling Stones’

truck, or whether it’s that the Rolling Stones truck has its

own sound, I’m not sure—but a lot of the tracks we did there

sounded very similar to the Stones. So rather than just forget

them, just for a joke we got a saxophonist from Supertramp to

overdub some sax parts on it and beef it up. If you listen to

the last Stones album without the overdubs it’s quite

surprising, and if you listen to some Beatles tracks without

the overdubs there’s nothing there. Some people specialise in

overdubs, but we don’t. We specialise in the basic four

instruments. But I don’t see any reason why, for one or two

tracks, we don’t have a nine-hundred-piece orchestra just for

the variety of it all. It’s a groove to do, so we’ll probably

get into something like that.

INFLUENCE:

Your best album to my mind was “Cricklewood Green”, and the

best track on that was “Circles”. I liked it because it was

acoustic. Are you planning more things in this vein?

This was a side trip again. It was a direct influence from

“Astral Weeks” by Van

Morrison, 1968

which moved me considerably at the time, and I used that

kind of format; the folk acoustic format, to say something I

wanted to say. Which was life going round in circles, which is

a pretty…..well, it was just a phase I was going through. I

mean. I still think that way sometimes. It was more of a folk

outlet to me….more like a truthful thought….a thoughtful

thought being sung instead

of spoken. I haven’t had any other ideas along the same

vein. We could always do something like that. We did acoustic

stuff on the first album and third album. It’s not planned. It

was where we were at, really. I mean, the last album showed we

could play some nice tunes, so I’m happy with that, that’s

past. I think we have to show now, more of our expression of

our own selves and our instruments.

|

|

New

Musical Express

May

13, 1972

This is the concluding interview by Simon Stable with

Ten Years After guitarist Alvin Lee. Here Lee talks

about his film ambitions, and discusses Ringo Starr’s

venture in the same field.

Simon: Alvin, I know

you’ve been into photography and making your own private

films for some time. Are you planning in the future to

make a full length feature film. With perhaps your own

electronic sound track?

Alvin:

I’d very much like to. At the moment I’m finding out how

much practical experience I lack to do that. However

perseverance could bring something out like that along

those lines.

Looking at the world of commercial films, it’s rather

disenchanting ---a bit like looking at pop singles. I’d

much rather be involved in something artistic, in making

a documentary of what a camera sees rather than making a

story about whatever---combining visuals and sound to

create an environment for the watcher.

All of this very much in the air at the moment.

It’s all gossip, depending on what type of filming or

video system is going to come out.

If you can get your hands on a video studio that will

convert your tape into film, you’ve got a lot more

technical control with what you can do with the visuals.

I’m well ahead on sound, I’m quite confident I can do a

good soundtrack to any movie, and I’m quite confident I

can do a good movie, but I’m not quite sure what

direction I want it to be yet.

Simon: Ringo’s doing this documentary of a rock ‘n’ roll

star…(Note: I believe this movie to be “That’ll Be The

Day” released in 1973 which also

features Keith Moon).

Alvin:

I wouldn’t want to get involved in anything like that. I

mean it could be good actually. Anything can be good,

but more likely than not it will be more like light

entertainment than an artistic masterpiece. Ideally a

film I make will be more like an album, being kind of

what happens with the camera with the sound at the time

of making it, and whether it’s good or bad will depend

on whether the heads behind the film are together. To a

point, you have to pick something good to say in a film,

the way that you have to pick something good to say in a

song. It’s the way that you do it that makes it artistic

or a rip-off, isn’t it?

Simon: Would you like to direct a film yourself?

Alvin:

I’d like to be involved in it, but I’d like practical

experience, meet somebody whose done some work on films.

Obviously, it’d help me a lot. I think I’d have a few

original ideas to contribute.

Simon: To get into another completely different kettle

of fish, as they say. What do you feel about Decca’s

release of Alvin Lee & Company. I know we mentioned it

earlier, but we didn’t completely go into it. Could you

tell me about the material on that particular album?

Alvin:

It’s left over from albums. It’s left over from

“Stonehenge”. “B” sides of singles which were put out

and were nothing to do with us anyway. When you do an

album, the record company will take a single off. It’s

part of their bread and butter.

You can’t tell them they can’t. It’s like saying

you can’t have any money. “Well”, you say “if you

release a single it’s the record company promotion for

the album, and not a single. We don’t do “Top Of The

Pops” and we don’t do any television . We won’t do any

promotion on it---so please yourself.” So they release

them for promotion of the album, and this album is the

“B” sides.

One’s a very early single we did at the same time we

recorded the first album. It’s not too bad: there’s some

nice jammers and things on it. At the time we turned it

down for release, so obviously we wouldn’t have chosen

it now. Everybody’s interested to see what kind of

material we decided not to put on our albums, so it’s

probably a good album for them to buy, but apart from

that, they didn’t consult us on what they call the

packaging of it. They did say they were going to use a

photograph of me and call it “Alvin Lee and Co.” If they

had I would have said no. What in fact I said was “If

they’re going to release an album of rubbish and left

over tracks, why don’t we look around ourselves and get

some good stuff put on? But they didn’t want to have

anything to do with that.

Simon: Would you object to Decca releasing “The Best

Of…”?

Alvin:

You can’t object. We have a recording contract which

everybody has to sign---they own the songs. We can’t

re-record any songs which we recorded with Decca.

They’ve got thirty-five original songs, some of which we

play completely differently now because of those deals,

that we signed when we were a bit green. We don’t even

own the rights to play the stuff, which is sad. But it’s

irrelevant really, because we’re more concerned in doing

new stuff. I don’t mind albums being released, as long

as people know they’re leftovers. If they did do a “Best

Of” it could be good and it could be bad. There’s

nothing we could do about it. The thing is, we could do

a better one, but they won’t communicate with us about

it.

Simon: How long have you been together as a band, and

how long in the present form?

Alvin:

About four and a half years. There’s no reason for the

band not to continue in its form for a long, long time.

A band as old as we are has a problem in keeping

ourselves in tune with the music we play. The more we

play, the more rehearsals we do, because the more used

we get to hearing what we do.

When you’re doing an extensive tour---playing every

night---what you’re doing is performing your music to

the audience every night. After awhile, although there

are subtle differences which a musician could get into,

it does tend to sound much of a muchness. You tend to

fall into what you did last night because “that sounded

good enough”. That’s the kind of attitude that comes in.

It’s really hard playing every night and travelling on a

plane. You don’t have much time to rehearse or think of

new ideas. This is why we work in tours rather than just

play. We do a tour for a month, play every night, then

throw new ideas around. If we can come out with three

new numbers for the next tour, well that’s enough to get

into. We recorded every night ourselves. We always

record ourselves live, and we listen back to the new

numbers, make changes to them, and they just progress.

Perhaps the way to stay interested in your own music is

to keep it progressing, keep it moving. There’s no

limitation in my mind as to what four musicians can do,

as long as they want to keep progressing. As long as all

the members of Ten Years After want to play, and want to

play better, and want to play the music to people, then

there’s no limitations. The only limitations are in your

own head, as soon as you start saying you’re fed up and

you don’t want to do this or that---you’re on the

downward slope.

It does happen, we do get fed up, instead of breaking up

we rehearse, which is the right way of doing things, and

although we probably won’t be playing the same numbers

in five years time, I don’t see any reason why we

shouldn’t be still making music in five years time.

I don’t see why there shouldn’t be people that want to

hear Ten Years After in five years time.

There might not be as many people as now---we might

phase out of popularity, but we don’t stop playing just

because fifty thousand don’t want to hear us. We used to

play to a hundred people, and I’d imagine we still

would, if it got around to that again.

We’re all opportunists---that’s about the nearest to

being a business musician---but we’re still not

out-and-out entertainers. We don’t put on a show---tell

jokes and things like that, a lot of the business is

getting into that now. You can go and see Jethro Tull

and you get an actual theatrical presentation, which is

OK….but I find it rather limiting to the band, because

once you’ve got your presentation set---once you’ve done

it five times---it all starts seeming like a cliché to

me. If we ever do a tour with a bad band, and they use

the same jokes every night, it all seems a bit

un-artistic to me.

Simon: Last year, it might have been two years ago now,

you nearly went to Russia, but you didn’t go there---are

you in the future planning to do Iron Curtain countries?

Alvin:

Well no, That’s one thing that “Woodstock” stopped

actually, because we were going to

play

the Iron Curtain countries on a basis of a cultural

exchange. “Woodstock” led them to believe it would be

more a rock ‘n’ roll concert than a cultural

exchange----which in all fairness, it probably would. So

I don’t think there’s much possibility of that happening

now. play

the Iron Curtain countries on a basis of a cultural

exchange. “Woodstock” led them to believe it would be

more a rock ‘n’ roll concert than a cultural

exchange----which in all fairness, it probably would. So

I don’t think there’s much possibility of that happening

now.

We get loads of letters now from Iron Curtain countries,

saying they can’t buy our albums there. They’re so

suppressed, silly things like they can’t buy a Ten Years

After album or anything. It really affects these people

and they write and say they’ll exchange their

Czechoslovakian folk records for anything we can let

them have. It’s sad, sad.

Something like music, man you should be able to go and

listen to, whatever you want. Ideally you should be able

to go wherever you want and say what ever you want, but

it does seem difficult in this over populated world.

Special Thanks to Simon's wife Judy Dyble for allowing

us to use her personal copy of this third article,

written by Simon Stable.

|

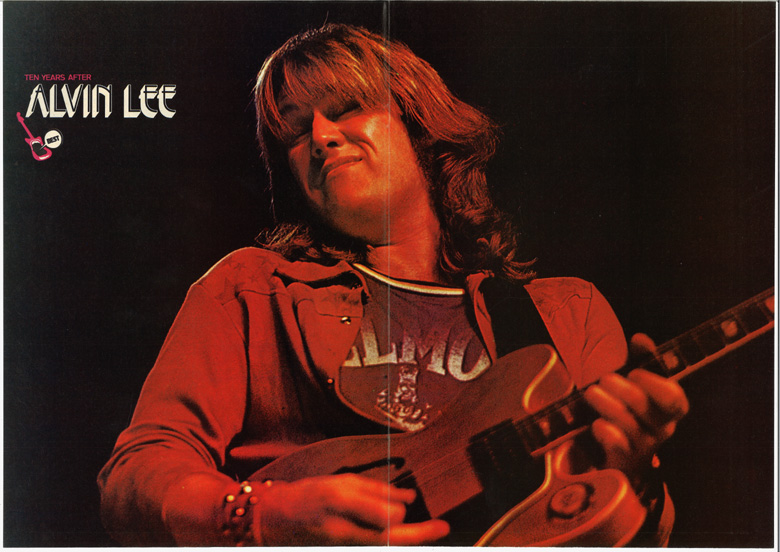

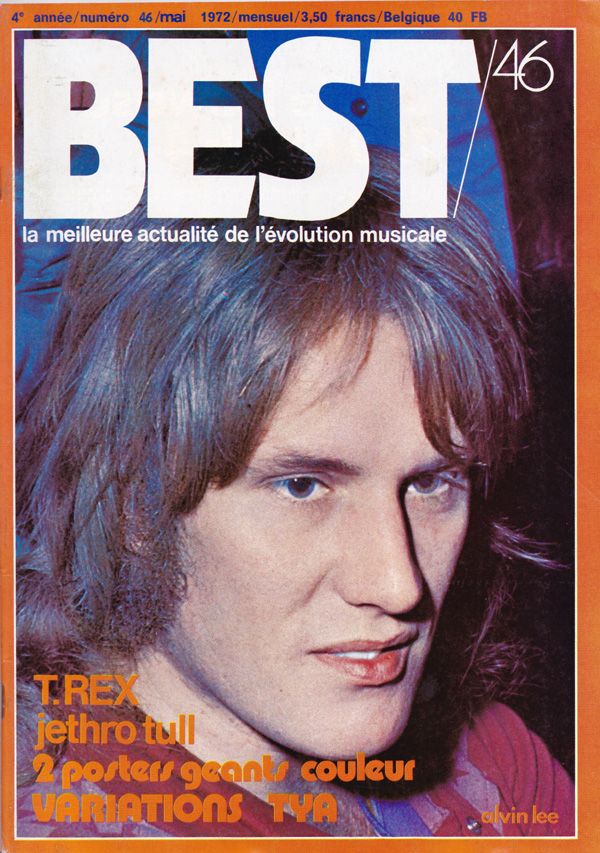

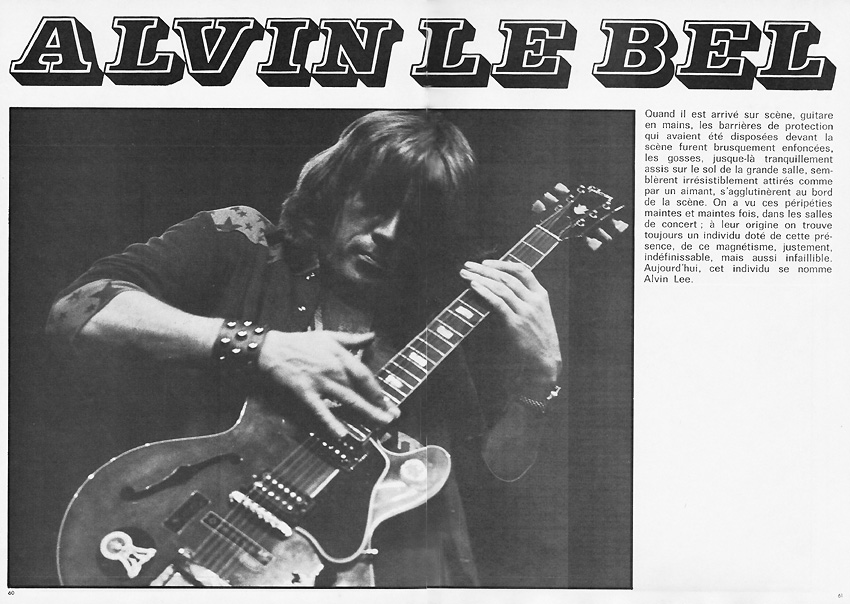

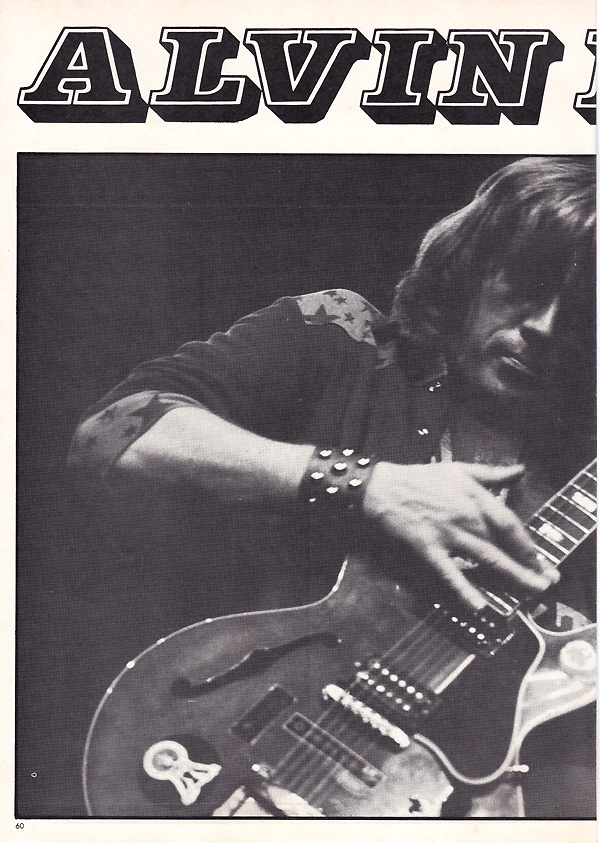

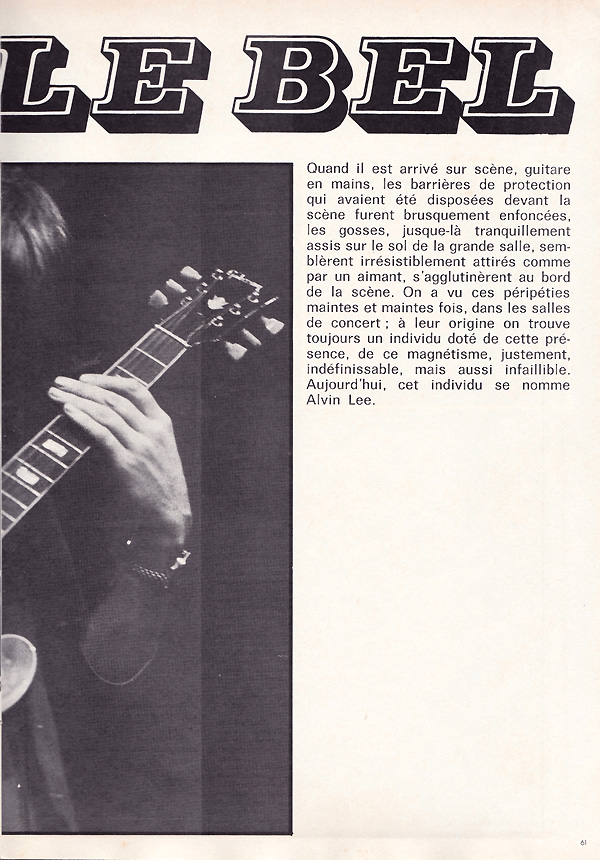

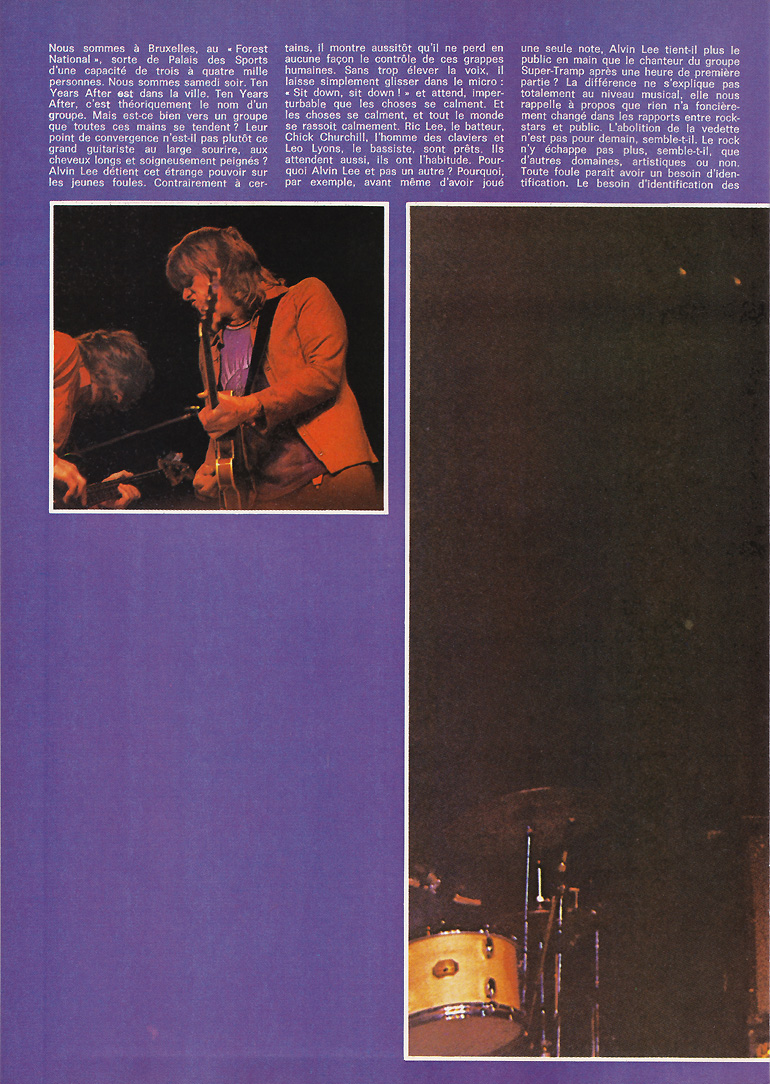

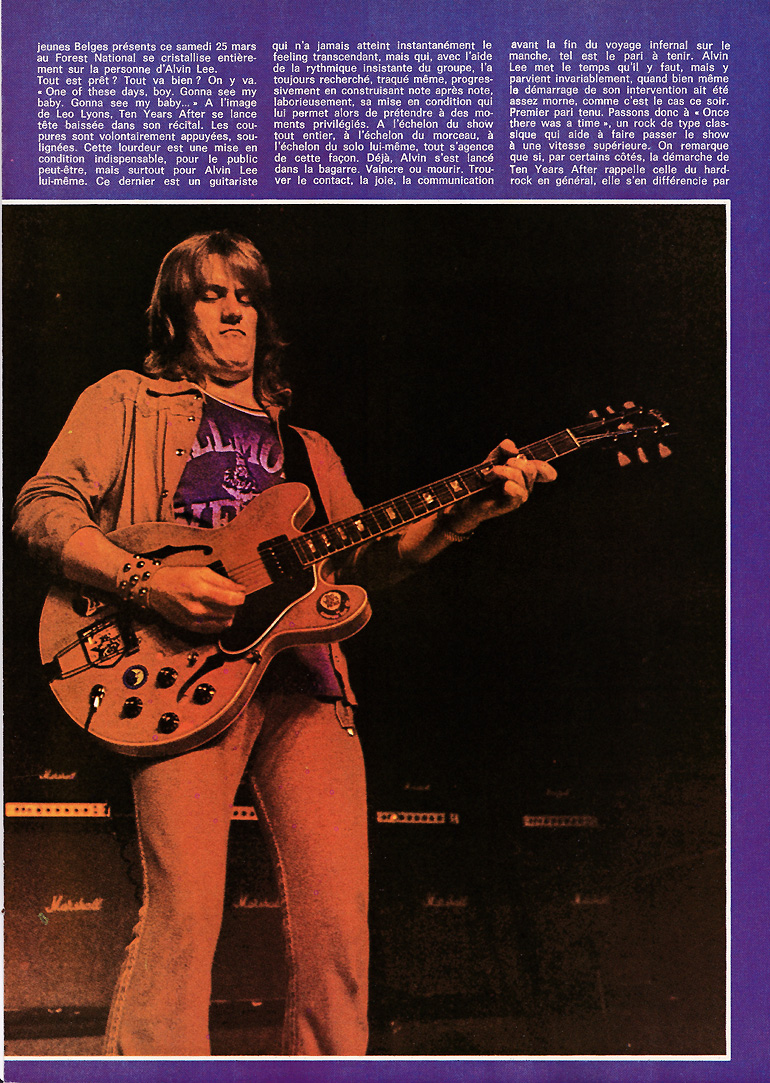

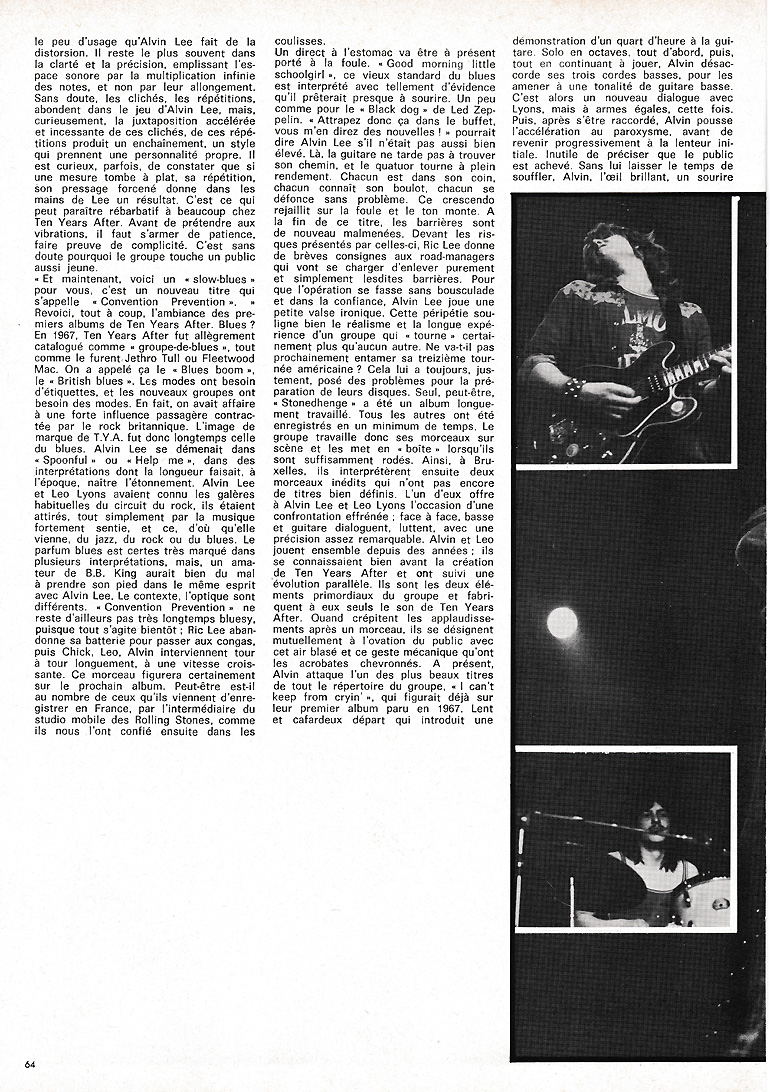

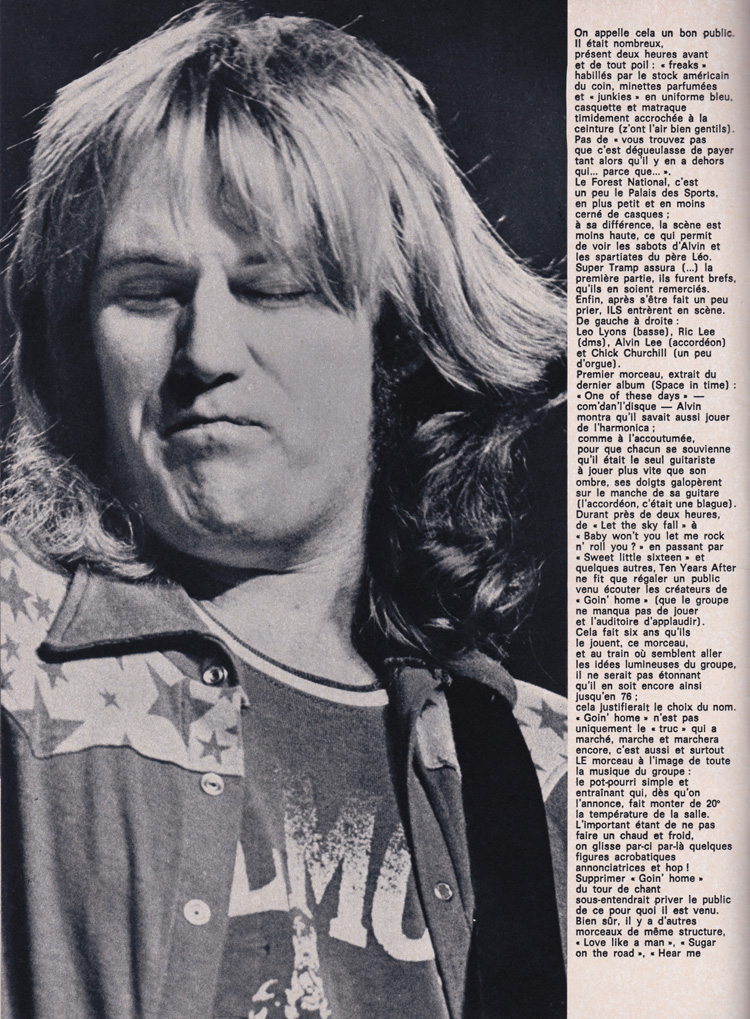

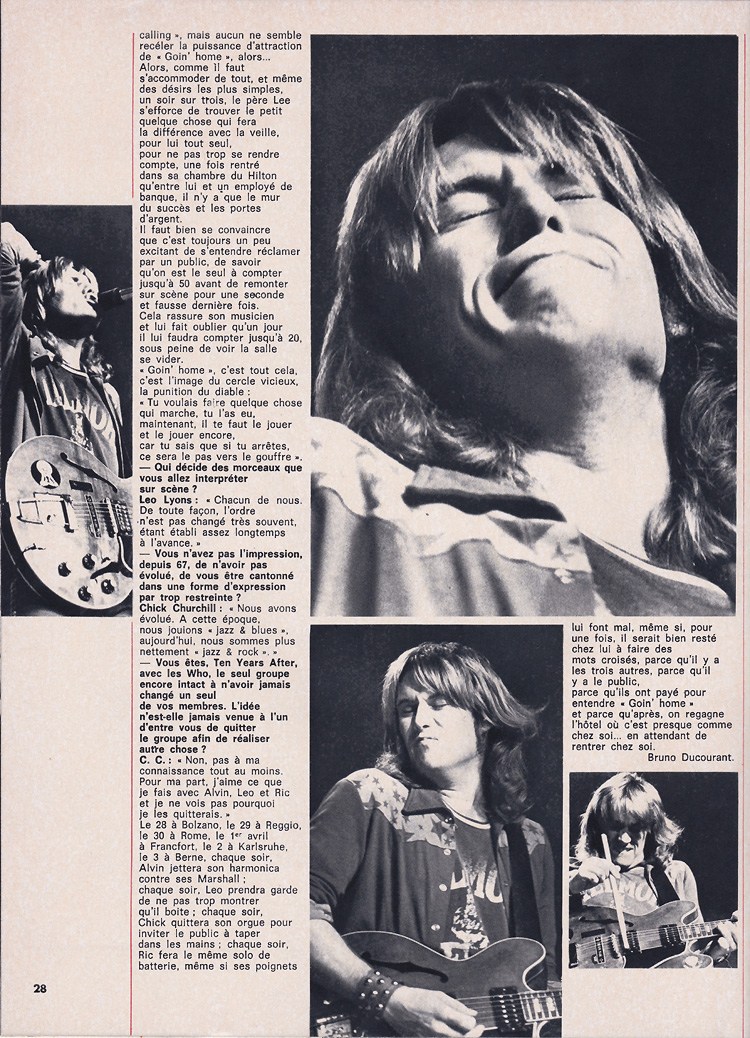

1972 May -

French Magazine BEST, vol. 46

"ALVIN LE BEL"

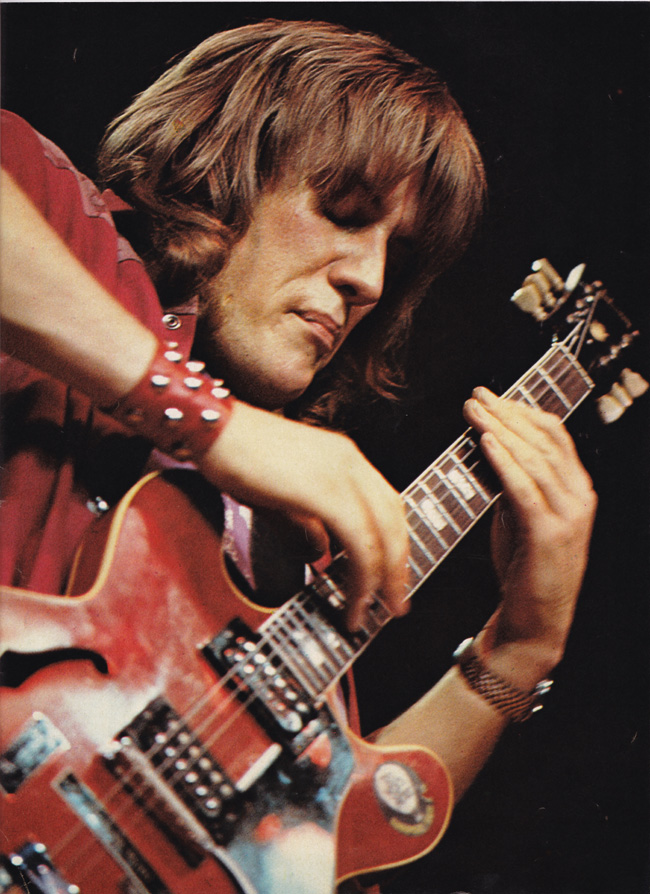

Photos by

Jean-Yves Legras

BEST -

page 60

BEST -

page 61

BEST -

page 62

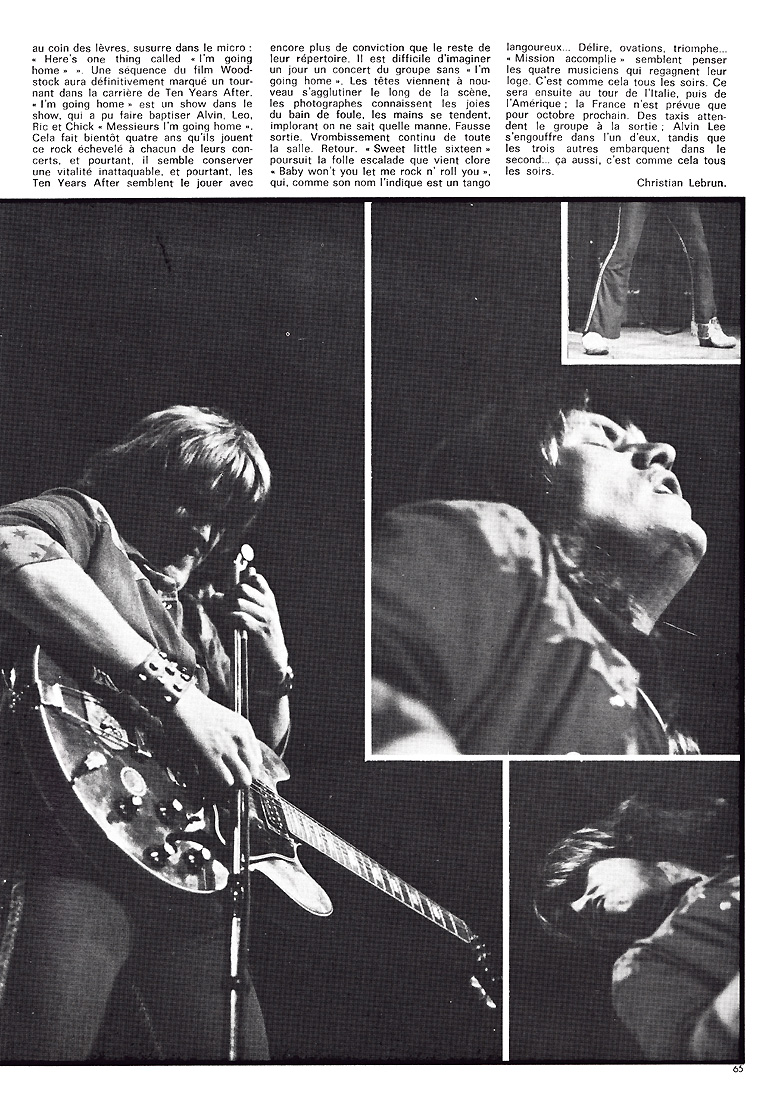

BEST -

page 63

BEST -

page 64

BEST -

page 65

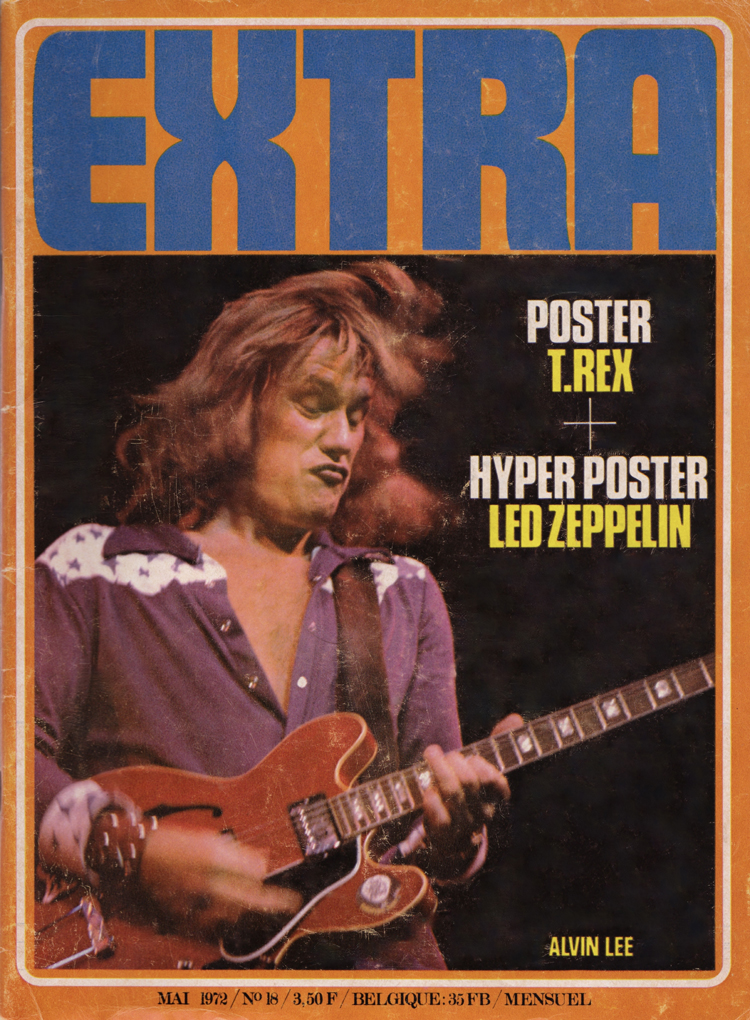

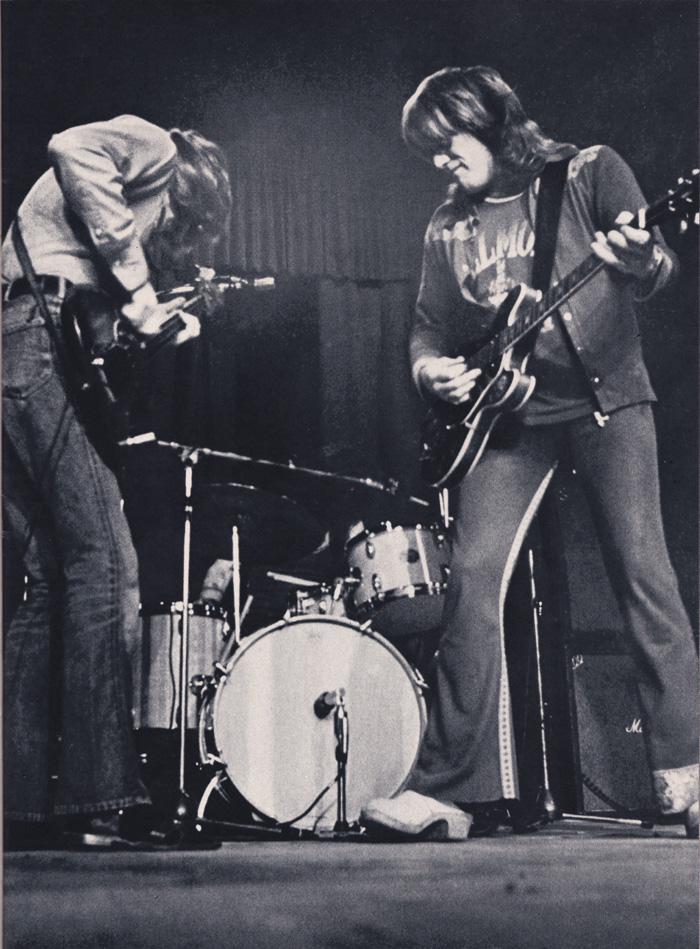

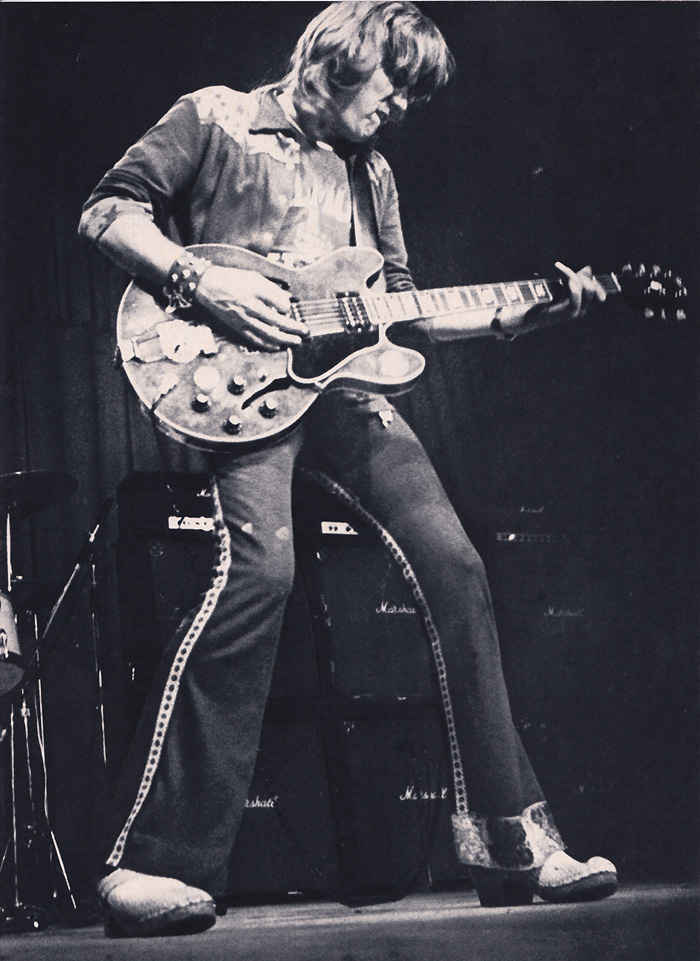

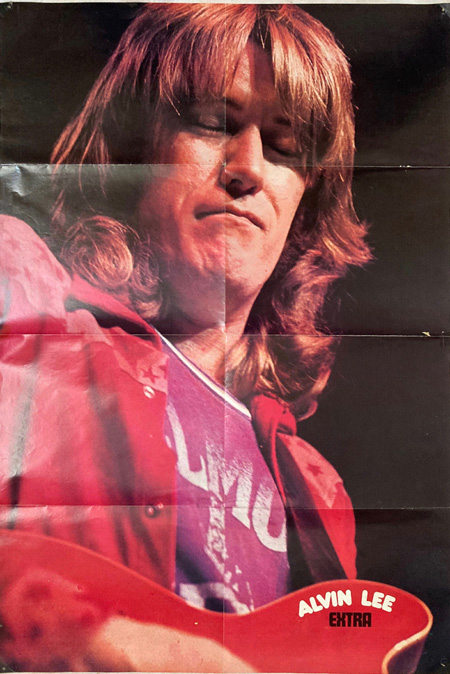

1972 May, French

Magazine EXTRA, No. 18

Photos: Claude

Gassian

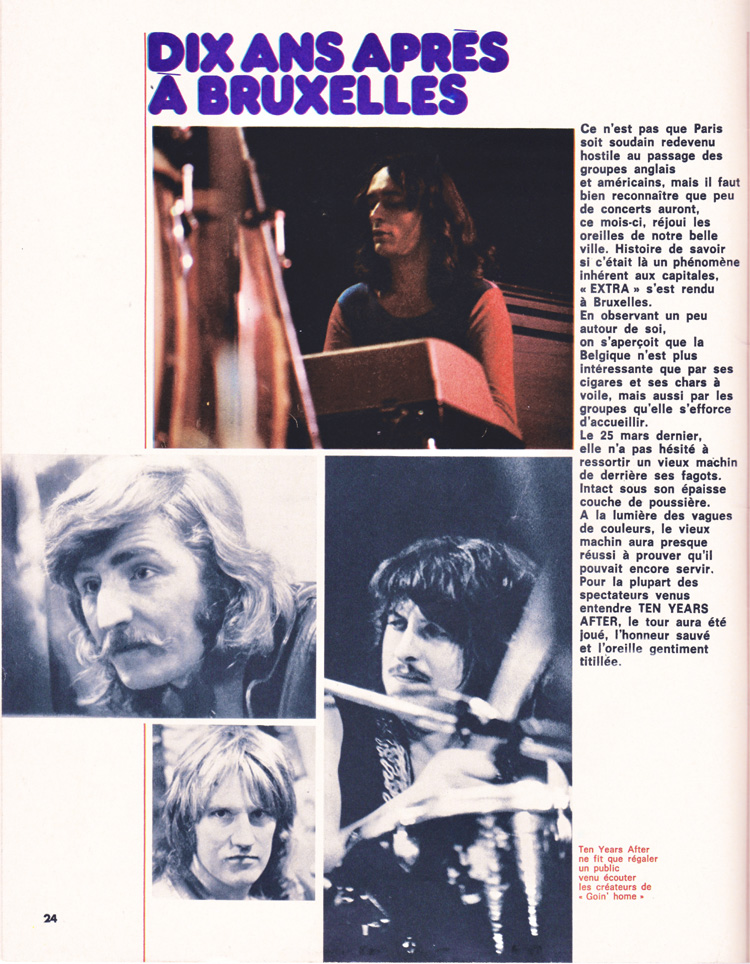

EXTRA -

page 24

EXTRA -

page 25

EXTRA -

page 26

EXTRA -

page 27

EXTRA -

page 28

EXTRA -

page 29

EXTRA -

Poster

|

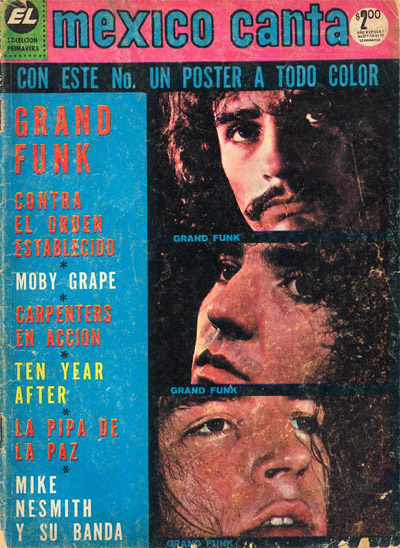

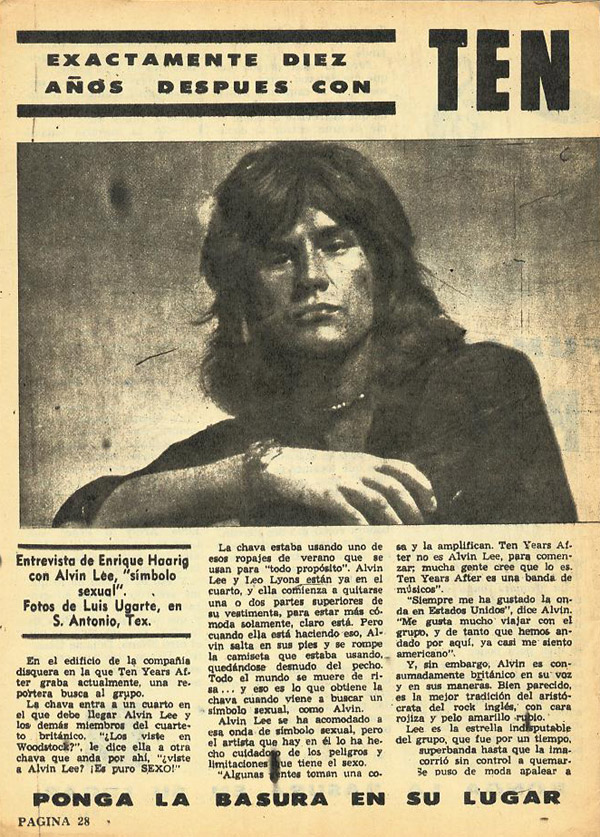

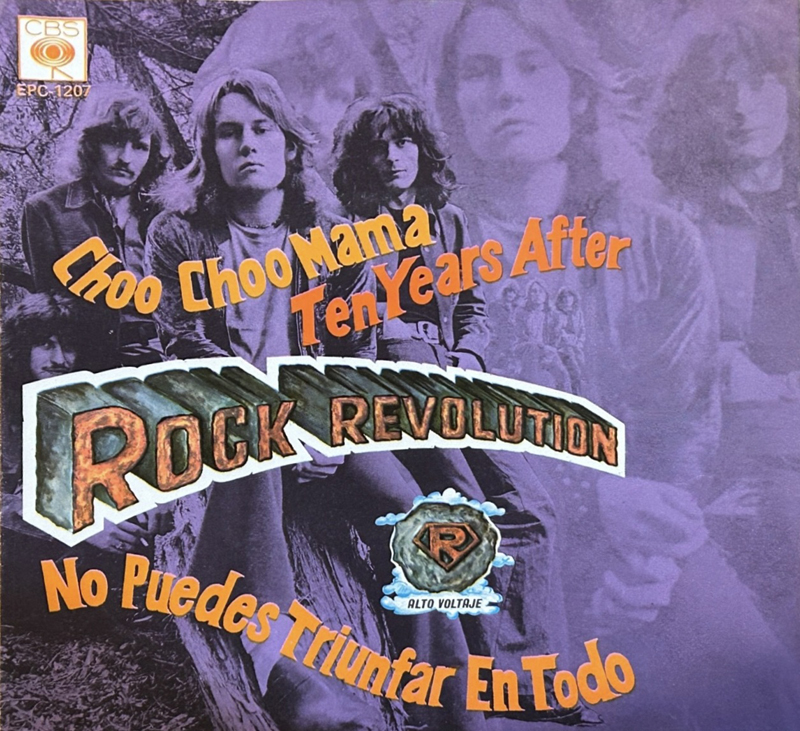

TEN

YEARS AFTER - MEXICO

Mexico Canta No. 377 - 16-VI-72

1972 - Single "Choo

Choo Mama" / "You Can't Win Them All" Edition

Mexico

|

|

|