|

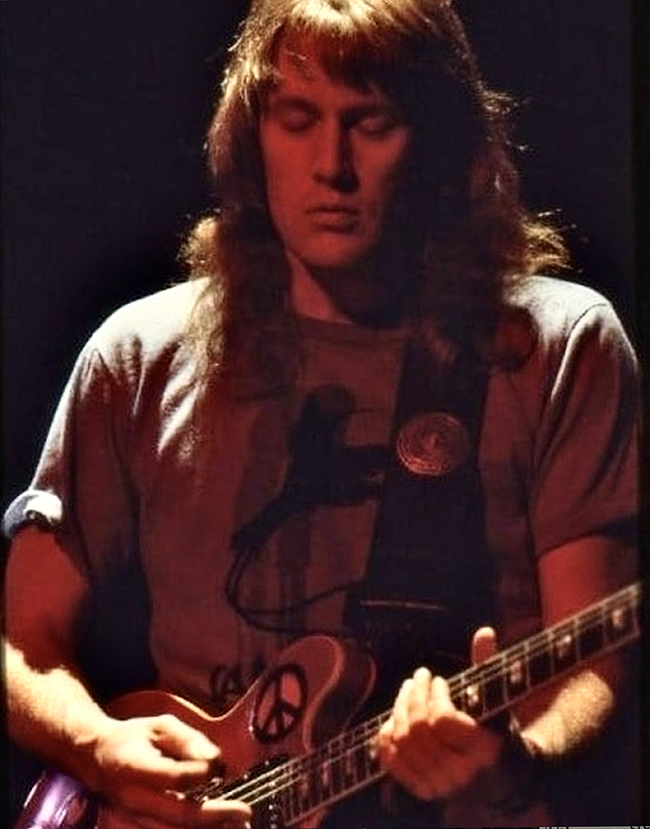

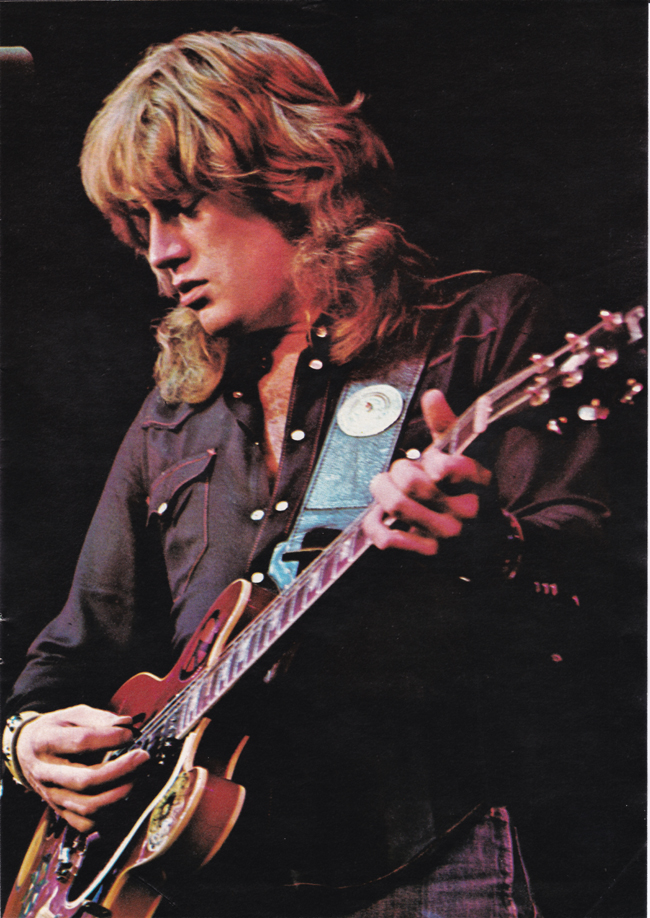

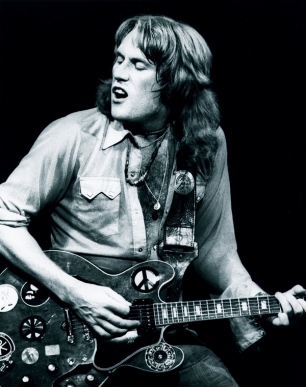

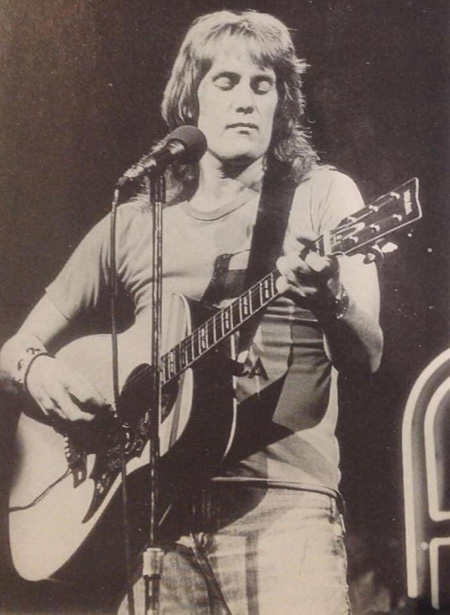

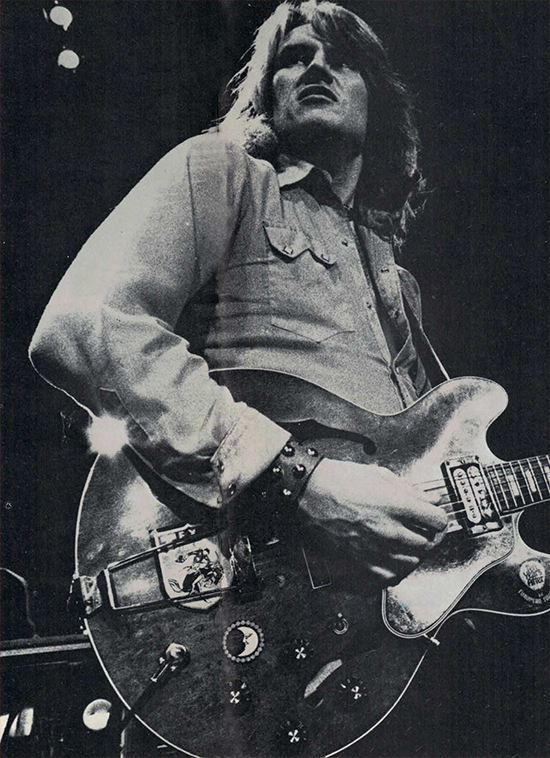

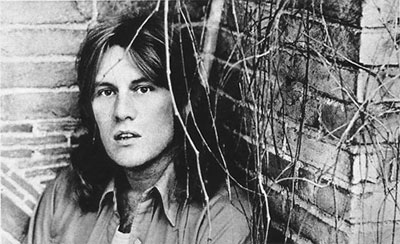

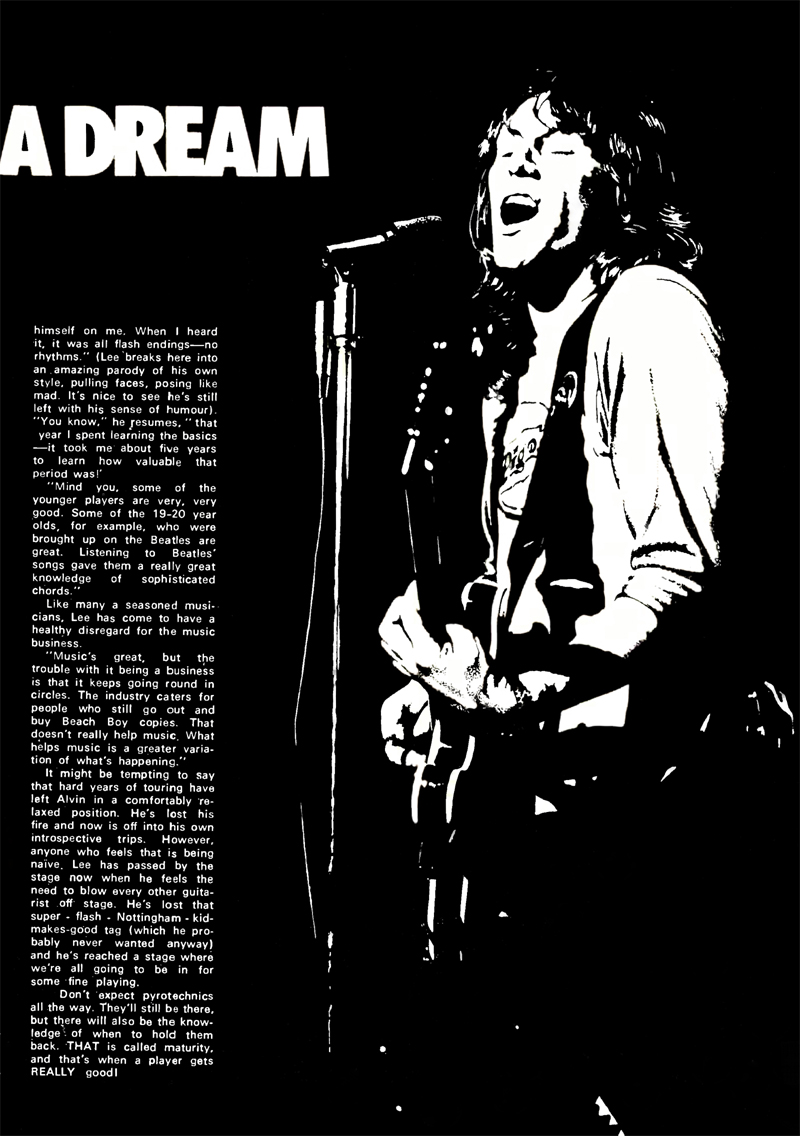

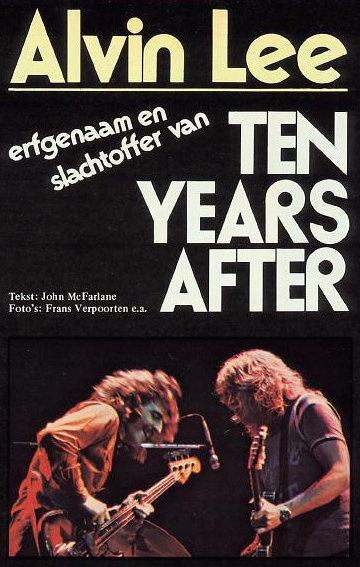

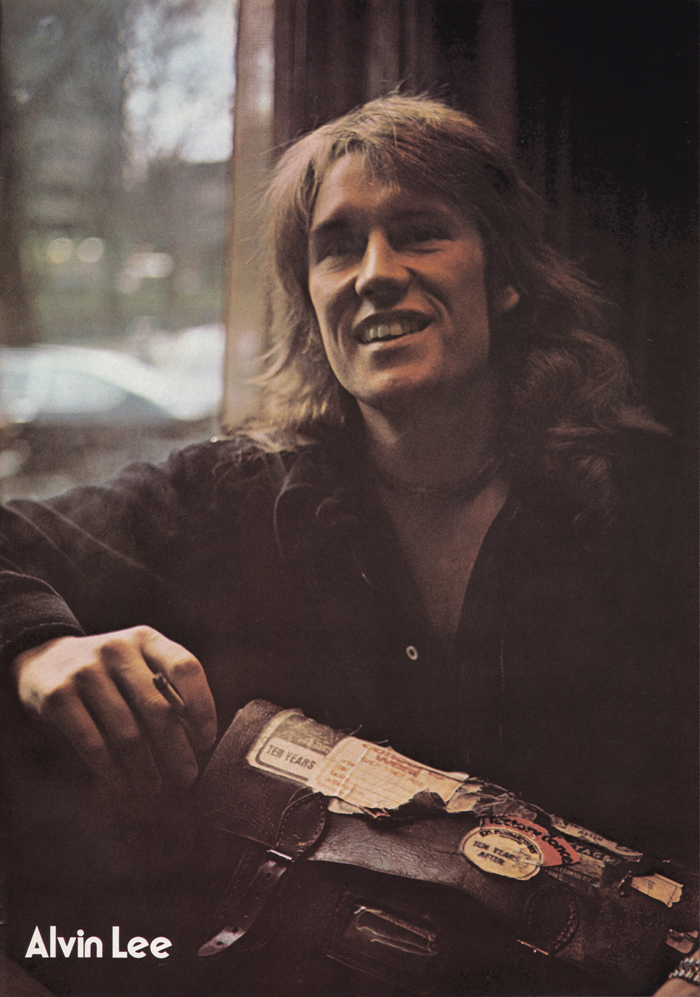

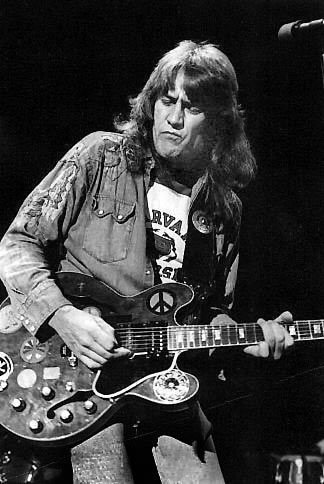

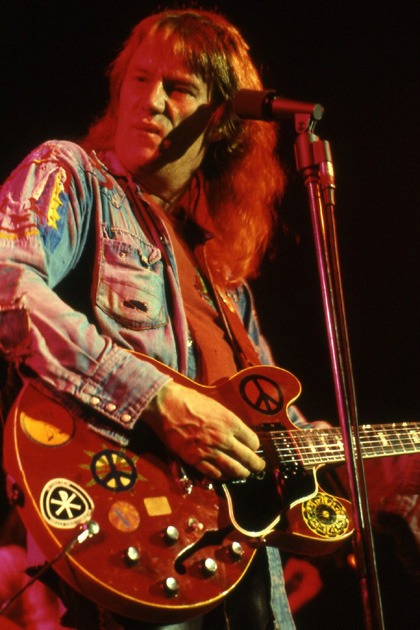

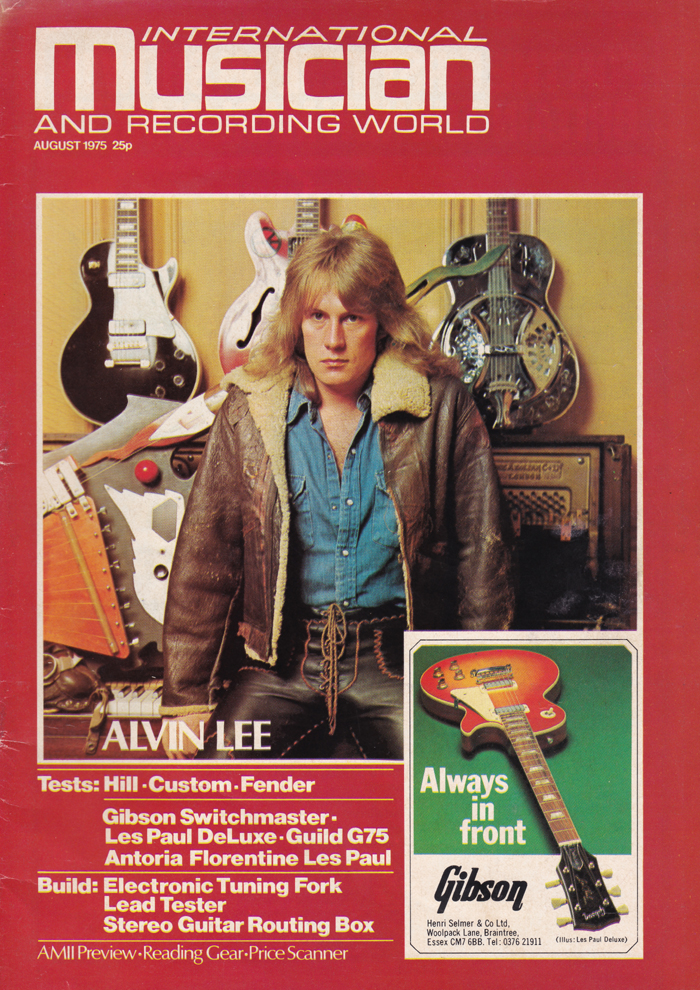

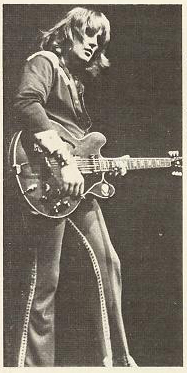

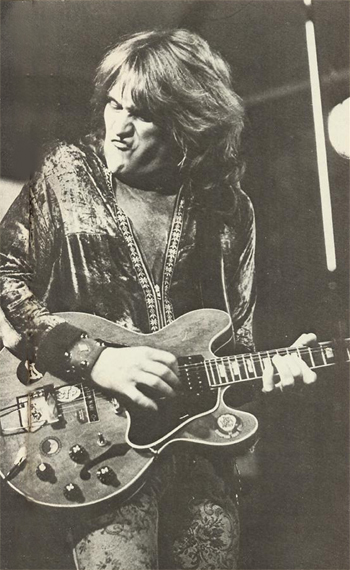

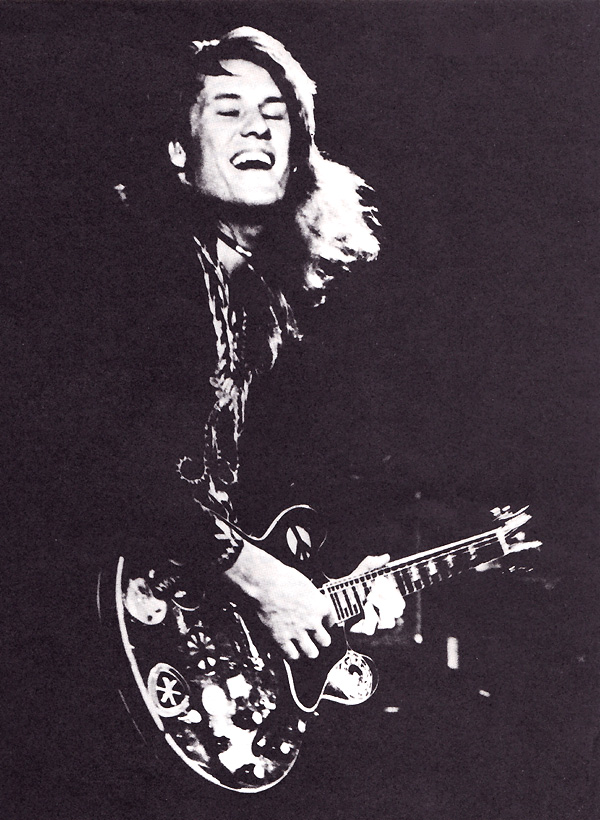

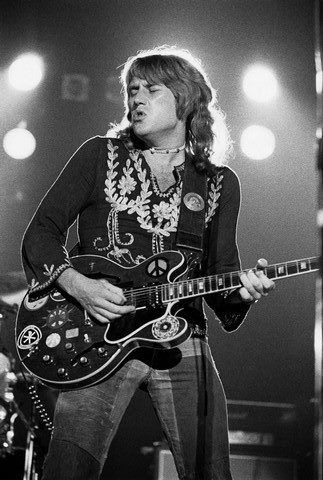

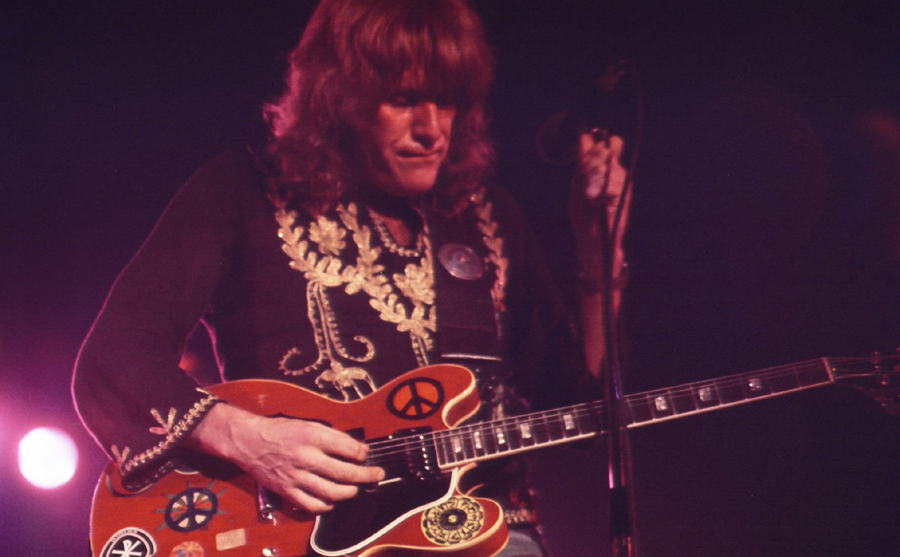

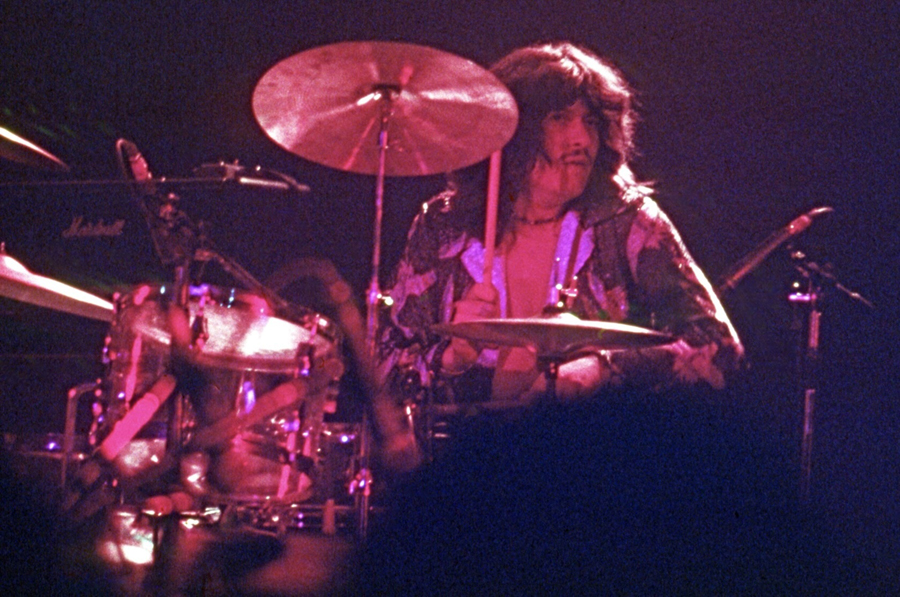

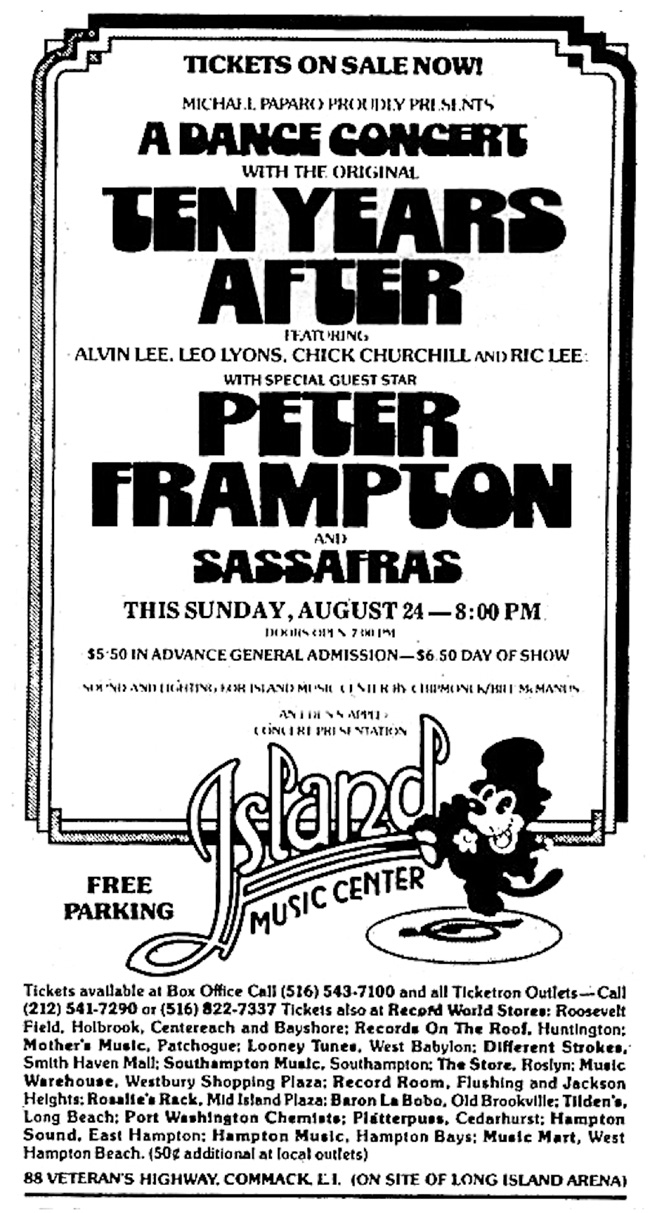

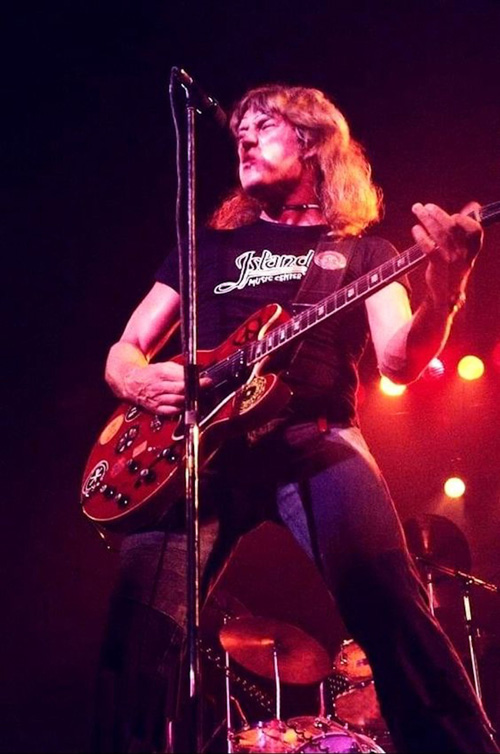

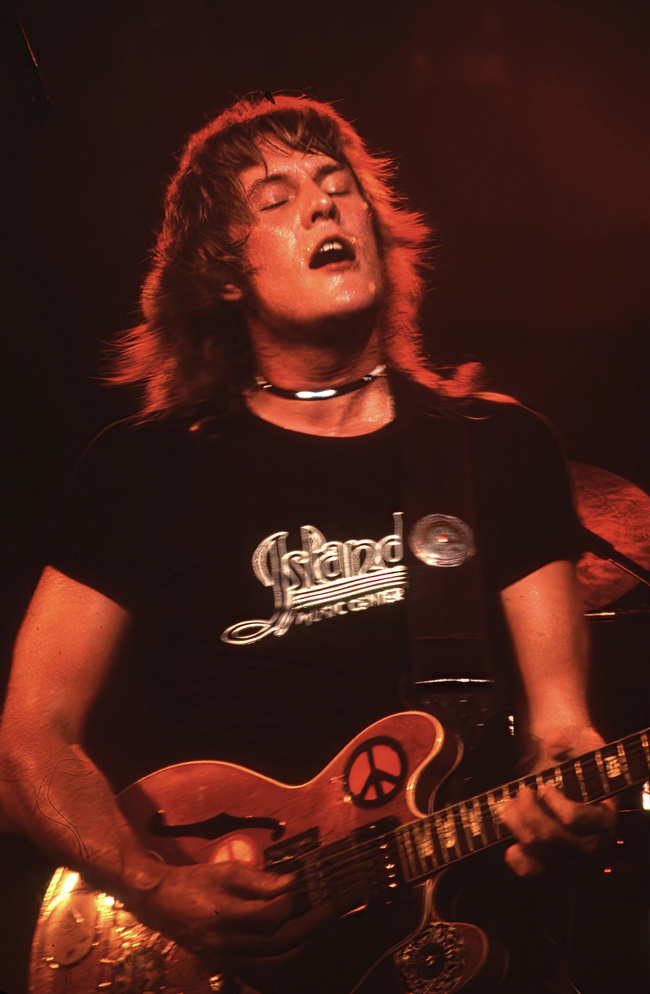

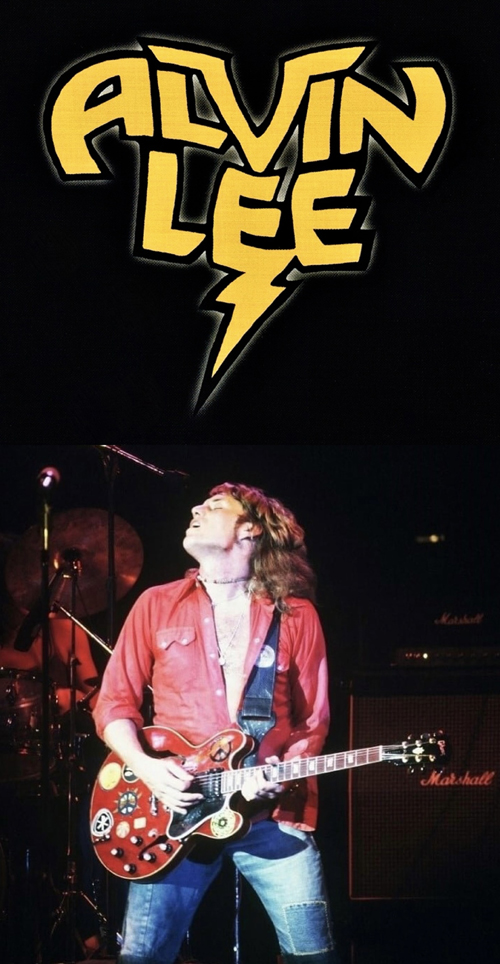

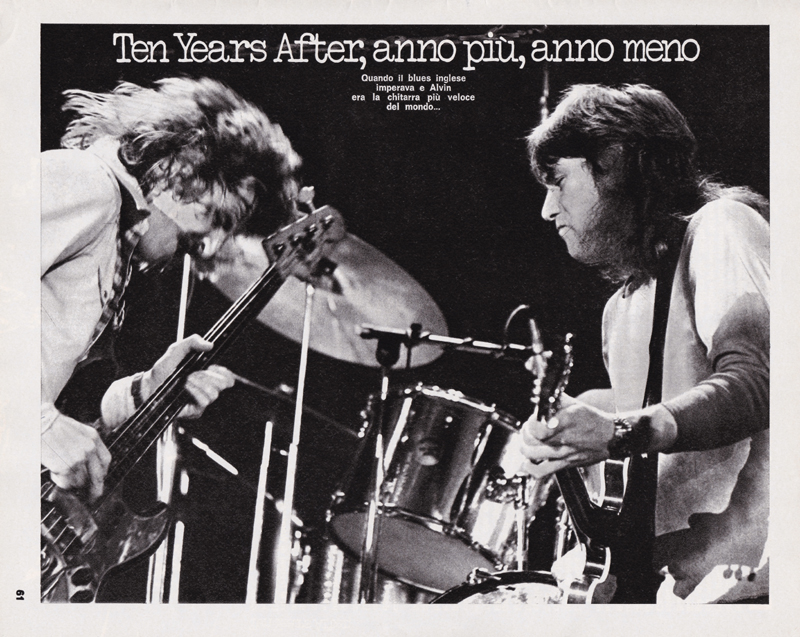

Alvin Lee and Ten Years After at the

Chicago Amphitheater 1975

Photographer: Jim Summaria -

www.jumsummariaphoto.com

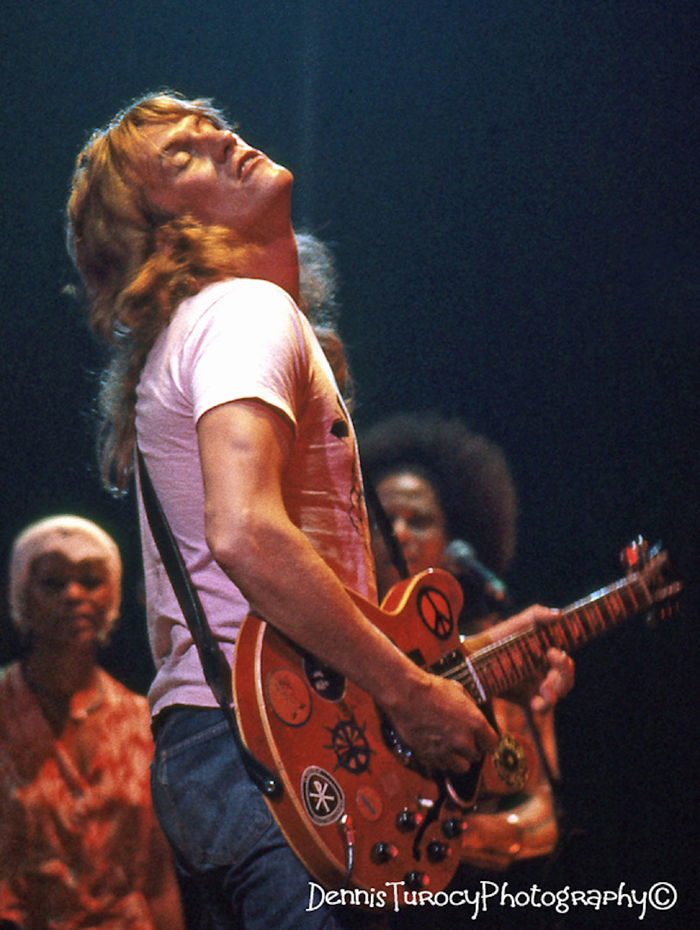

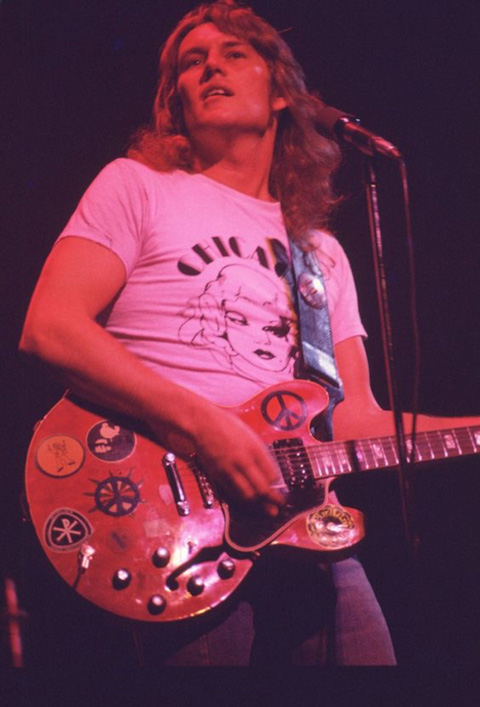

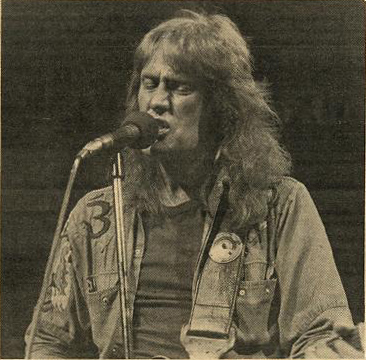

January 16, Alvin Lee & Co., Pittsburgh

Syria Mosque - Photo: Dennis Turocy

|

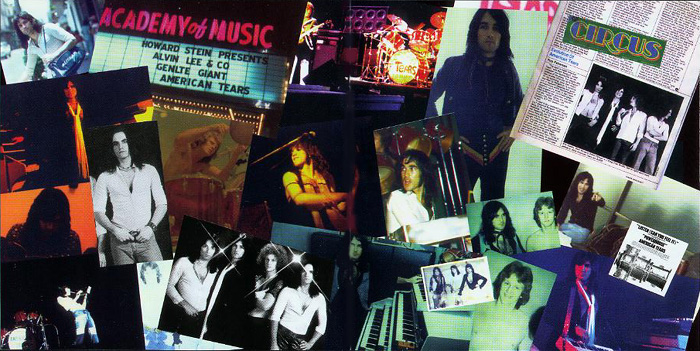

January 18,

1975 – At The Academy of Music – New York, NY

On Bill Are –

Alvin Lee & Co – Gentle Giant – American Tears

American Tears,

were a “Power Keyboard Trio” who recorded three albums

for Columbia Records during the mid 1970’s. Their music

ranged from progressive and symphonic rock, to keyboard

oriented “Pop” songs of the era, as the band emphasized

adventuresome arrangements and musicianship. On their

third album “Powerhouse” they added a guitarist, Craig

Brooks, which gave them access to large vocal harmonies

and ultimately evolved into the band “Touch”. Touch

recorded two albums for Atlantic Records – While all

three of the American Tears albums are now available on

CD format. “Powerhouse” Japan Import also includes the

band’s second “single” – “Born To Love”. Their three

albums are: Branded Bad – Tear Gas – Powerhouse 1977.

Out of American Tears came the band “Touch” in 1978

Mark Mangold –

Keyboards / Songwriter – Glen Kithcart – Drums and Craig

Brooks all guitars. The line-up was completed by adding

bassist Doug Howard. Mark Mangold, in collaboration with

Michael Bolton composed the song, “I Found Someone” was

recorded by Laura Branigan – but ultimately became a big

top ten hit for Cher.

From Dave: I recommend American Tears “Powerhouse”. I

bought the record brand new back in 1977, having never

heard of this band before. I was so impressed, that 34

years later I just bought the Japanese import on cd, and

it still sounds as fresh and new as ever. Sure it’s as

much pop, rock and ballad as much of the middle to late

1970’s was, except this album was something special –

for what it didn’t have on it – excess! It’s tasty, not

sappy and with enough rock hooks, licks and energy to

make it enjoyable and memorable. It’s like finding an

old friend once again – welcome back my friend! |

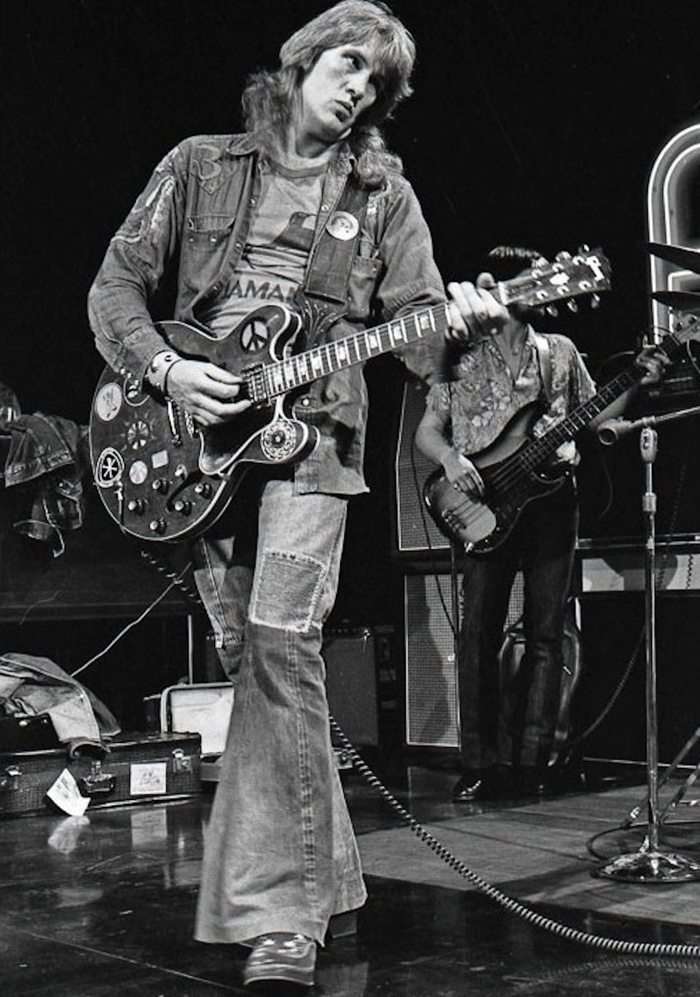

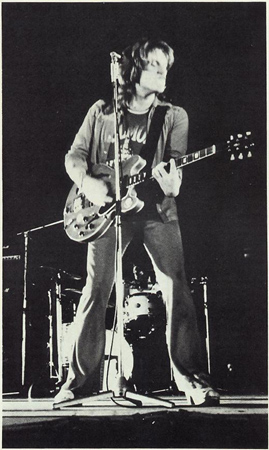

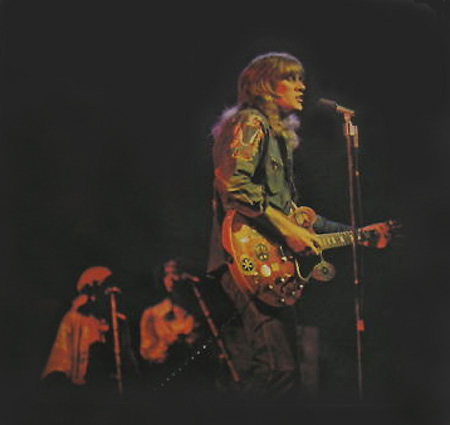

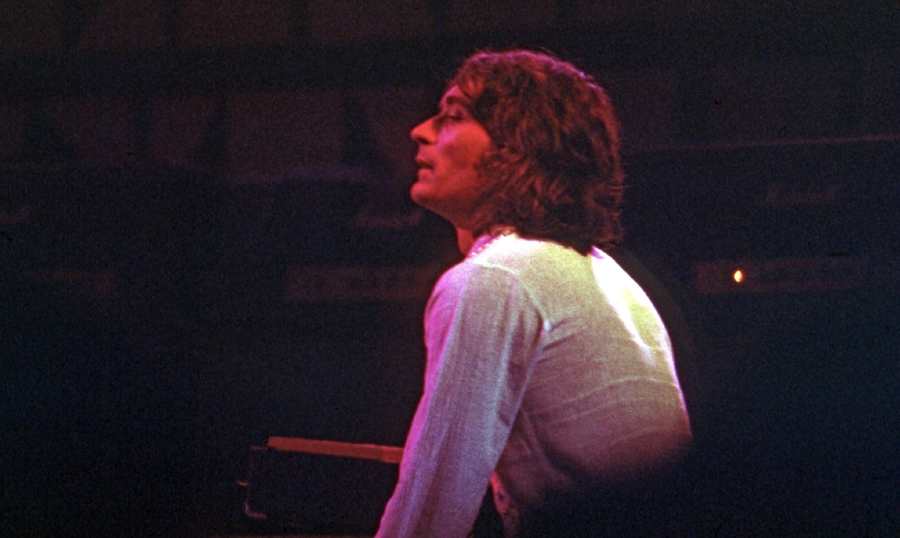

January 19, 1975 - Alvin Lee & Co.

at Lisner Auditorium,

George

Washington University, Washington, DC

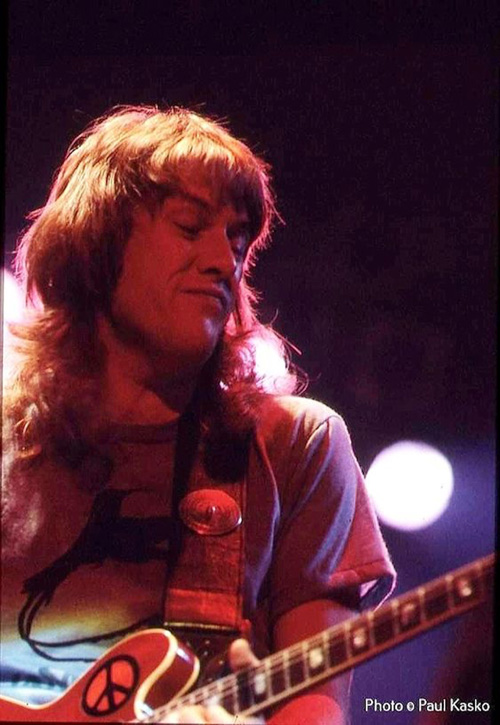

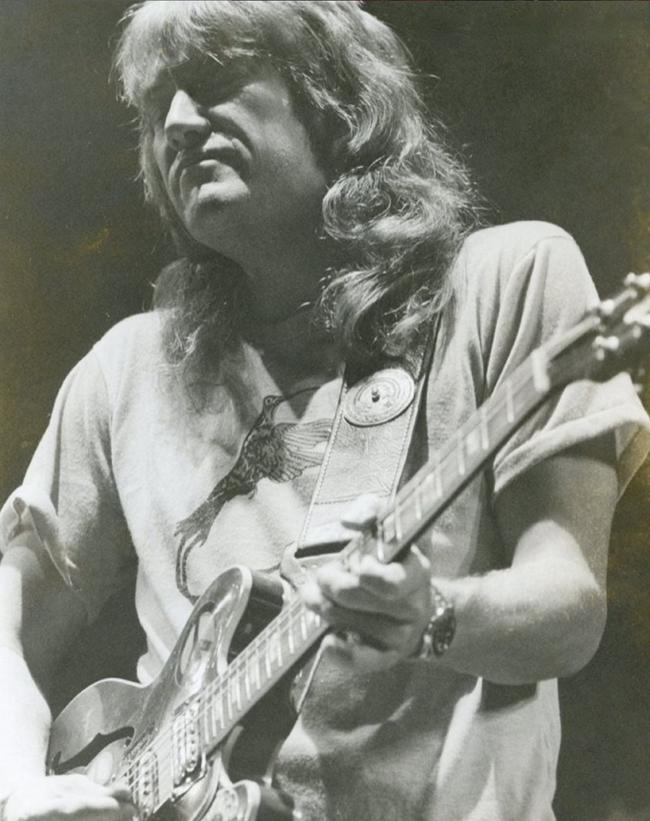

Photos: Paul Kasko

Photo: Paul Kasko

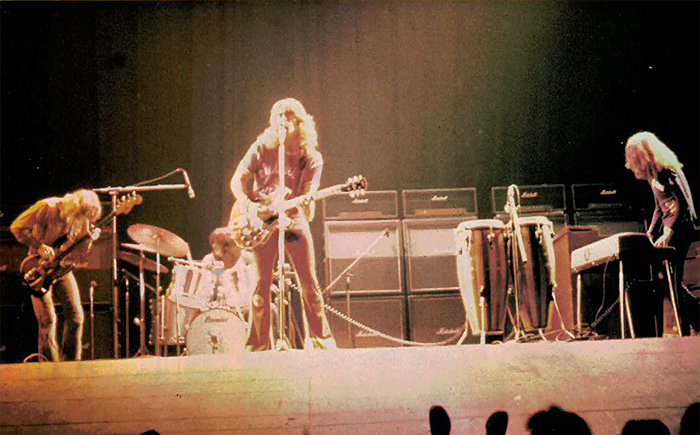

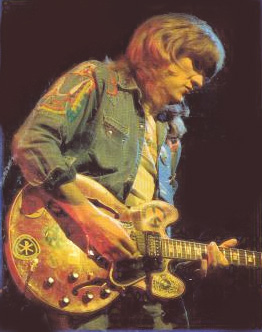

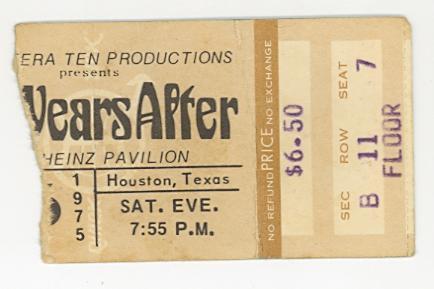

January 28, 1975 - Alvin Lee & Co. at

The Auditorium Theatre, Chicago

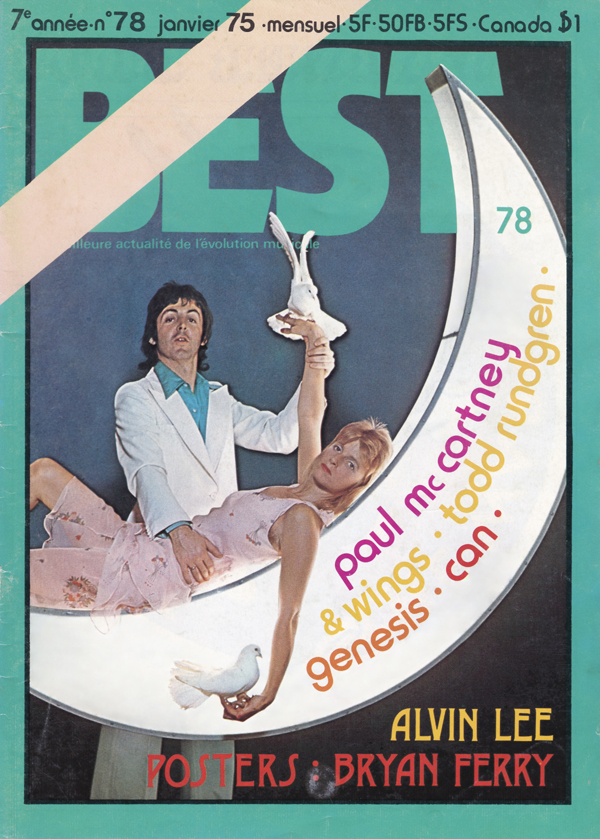

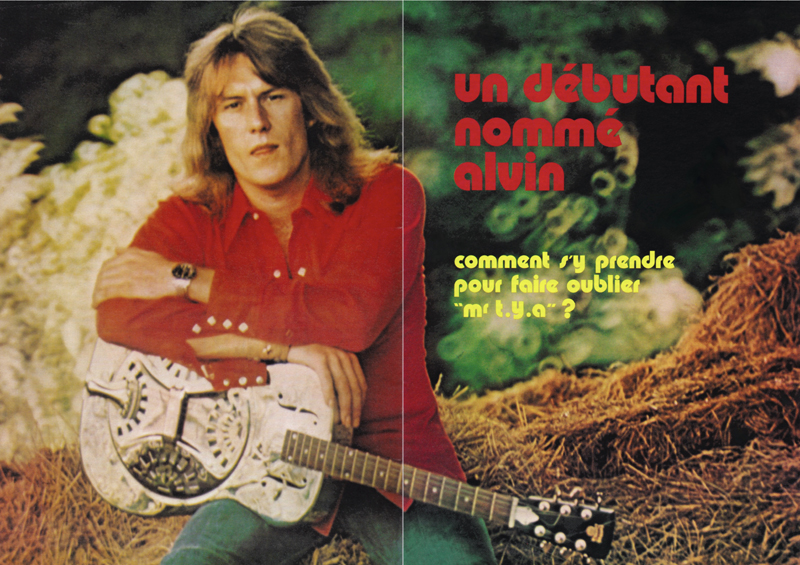

January 1975 -

BEST Magazine, France

Front Page

page 26 & 27

page 28

page 29

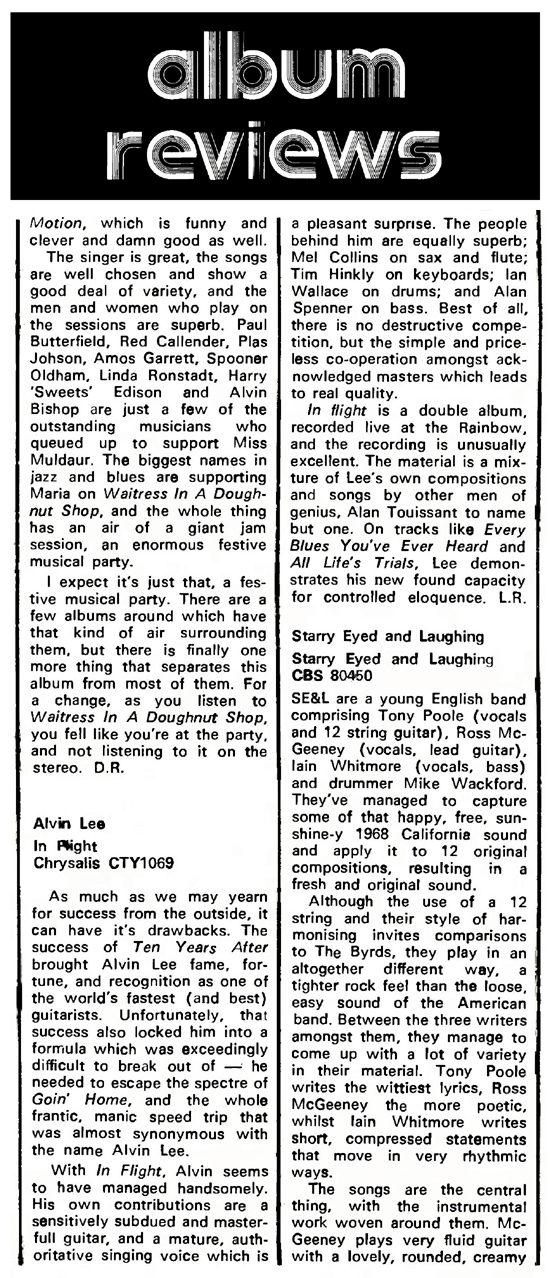

January 1975 -

BEAT INSTRUMENTAL Magazine, England

"In Flight"

Album Review

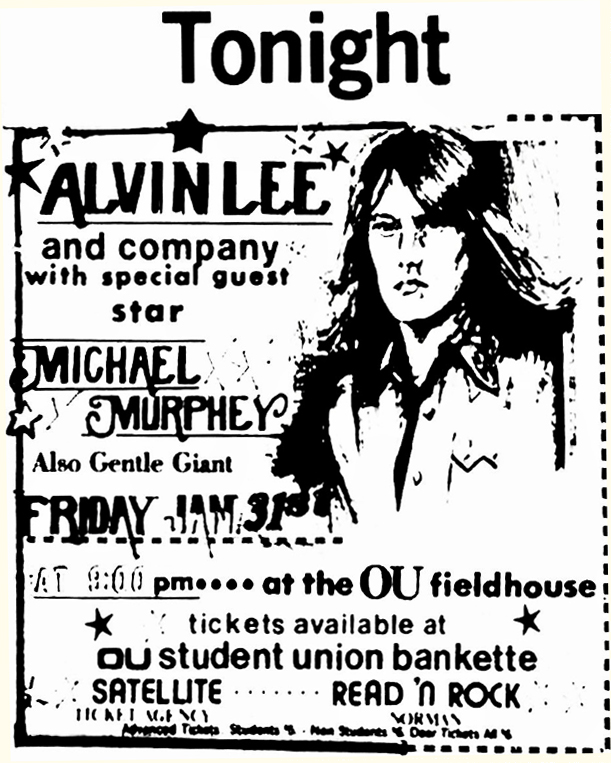

January 31, 1975 - Alvin Lee &

Co.,

Norman Oklahoma,

Field House At University Of Oklahoma

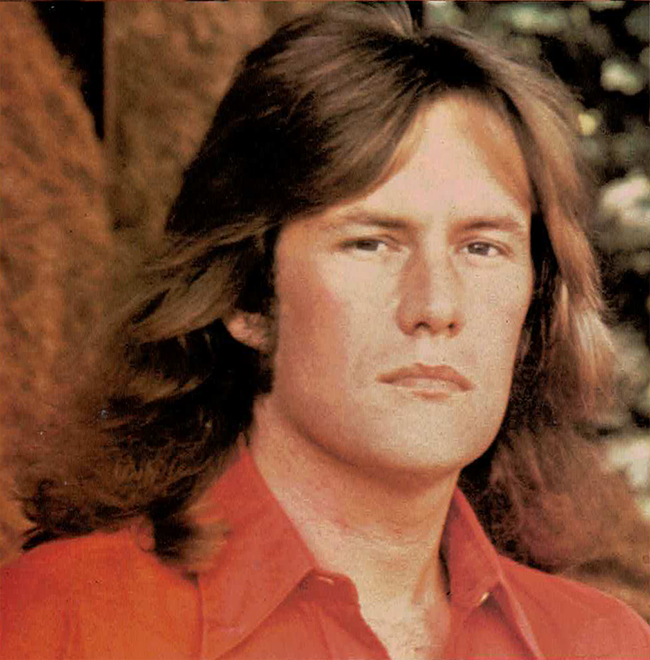

February 12, 1975 - Alvin

Lee, backstage at Paramount Theatre, Seattle

Photo: Brad Matisoff

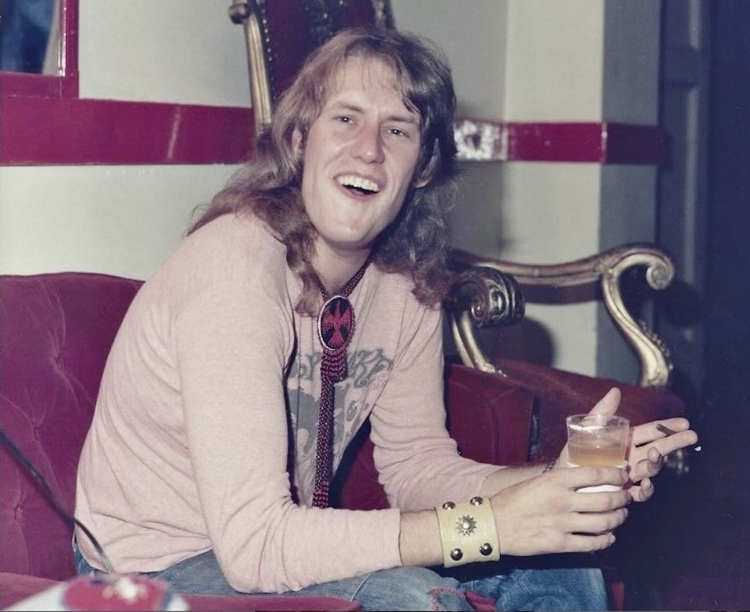

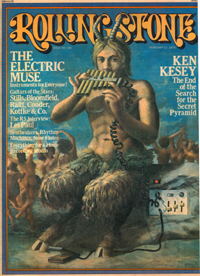

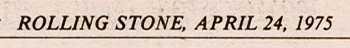

ROLLING STONE

February 13,

1975

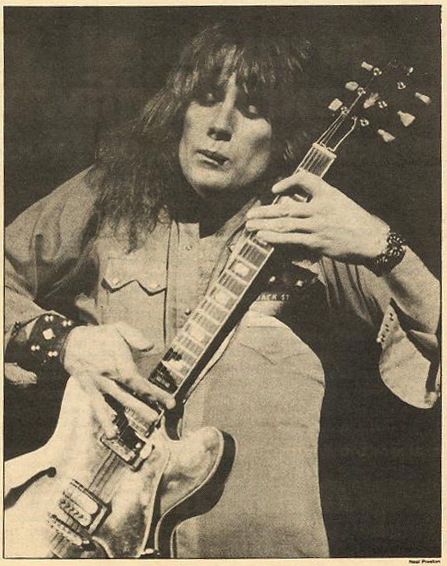

With Ten Years After behind him, Alvin Lee finds

his way with Alvin Lee Company

London---Alvin

Lee is on the road again, and this time he’s not going

home. Inspired by a special London concert

last

March without Ten Years After behind him, Lee bid an

indefinite good-bye to his colleagues of seven years.

Ten

Years After might someday work together again, he says,

but the immediate future belongs to a new band called

Alvin

Lee and Company. They are now on a six-week U.S. tour, and

Lee’s Rainbow Theatre concert has been

released

as an album, In Flight. “Well, Lee says, grinning in the

corridor of his countryside home, a gold record

for

the Woodstock album hanging overhead, “I’m certainly

not going to be playing “I’m Going Home.”

In

a sense Lee is home, playing the kind of music that earned

him that first initial recognition. The new band

creates

a sense of déjà vu, all of the players going back to

their roots. There’s bassist Steve Thompson and

keyboard

player Ronnie Leahy, former member of Stone the Crows,

Maggie Bell’s starting ground. Drummer

Ian

Wallace and reed player Mel Collins are former members of

King Crimson and have contributed to

numerous albums. A percussionist and several backup singers

complete the group.

The

rejuvenation of Alvin Lee as a musician started before the

London concert with an album with Mylon

LeFevre,

On the Road to Freedom, the first step out of the musical

prison TYA had become.

“It

got to feel like an old marriage. I started to get the

seven-year itch. I wanted a band,” he says, “I

didn’t want

it

to be Alvin Lee showing off his clever tricks, which is

what was beginning to happen with TYA. It all became too

mechanical.”

The

machinelike atmosphere became oppressive during the

band’s last American tour. “It got to the point where

American

tours were boring. It was too much like a job; the fun was

gone. Everything ran too smoothly. It was

just

an endless cycle of tours and albums. On that last

American tour it got so bad that each day I’d look

forward

to

a different airline, a different colour scheme, a higher

hotel than the night before.” TYA began to feel like a

treadmill,

just

what Alvin wanted to escape through music. Before

Woodstock, TYA was just another entertaining British blues

band dabbling in jazz. After the infamous three-day

festival the band—Alvin in particular—was elevated to

superstar status, confined to a set pattern.

“Yeah,”

Lee shrugs. “We were a different band before Woodstock.

We’d play the old Fillmore and be able to just play.

We

had a respectful audiences then who would appreciate a jam

or a swing. But after Woodstock,” he winces,

“the

audience got very noisy and only wanted to hear things

like “I’m Going Home.” “I’ve always been much

more of

a guitar picker but I began to feel forced into a position

of being the epitome of a rock & roll guitarist.

Originally

TYA wanted to make it without having to compromise to pop.

It worked for a while but

after

five or six years the fun went out of it for me, a lot of

the music went out of it. And, he smiles shyly,

“all

I wanted to be was a musician. With this new band I feel

relaxed. I have enough freedom that I don’t feel

pigeonholed anymore.

“Everyone

thinks of the group as my solo thing but I think of it as

a band. Everyone in the group is free,

everyone

is their own musician. It’s up to each individual what

they play. “This band is just good fun. The

excitement

of not knowing what will happen next is great; it’s a

welcome change. It really is like going back to

the roots; feeling enjoyment in the music again is how TYA used to feel.”

On

their recent European trek, audiences shouted for the band

to boogie, and to play TYA standards, but

were quickly pacified by the new music. Standing out front,

Alvin Lee taps his foot gently and takes time

finding

the right notes. Gone are the bullet like barrages of

lightning-fast solos, the archetypal superstar

Grimaces

, replaced by fluid playing and an anonymous grin. The

material is strictly non-TYA.

“Even

though the songs are mine, it’s the music of the band. I

guide a lot of it but it’s still down to the group.

“One

might get the impression that this time around the

guitarist does not dominate the proceedings. “If

anything, Mel gets his freedom he steers the band toward a

kind of nouveau jazz, bordering on the

realms

of John Coltrane, Chick Corea and Herbie Hancock- type

number and then something like Money Honey.

That’s

the kind of musical freedom I like: jazz, rock, blues,

anything. “You adopt different attitudes when you

Play

different music. This band is more reserved, more

disciplined, more tasteful. But the discipline is good. If

everyone

were to race off on their own solo it would be a mess. My

solos are more tastefully conceived now,”

he

nods his head in agreement. “But I still get going in

places. It’s just that I build up to it now. I don’t

race

off

on a solo. I take my time.”

While

TYA remains in a state of permanent limbo, this band

exists at the least through spring. On return

from

the American tour, they will record an album. But Lee is

quick to add that there might be changes:

possibly

another album with Mylon, perhaps a tour.

Alvin

Lee refuses to commit himself anymore.

By

Barbara Charone

|

|

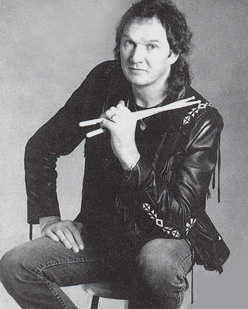

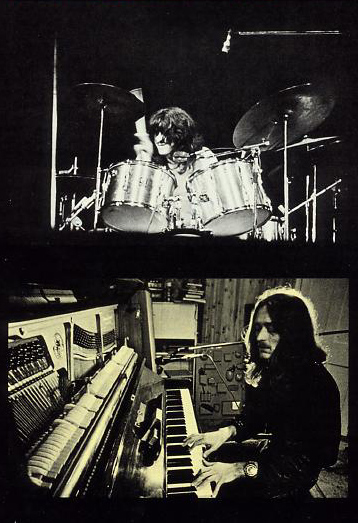

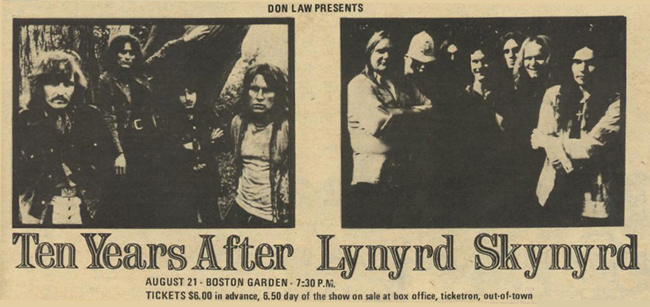

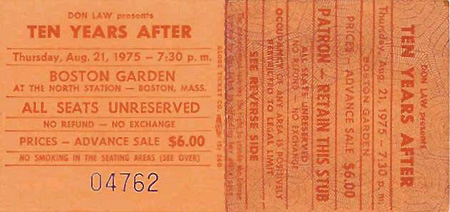

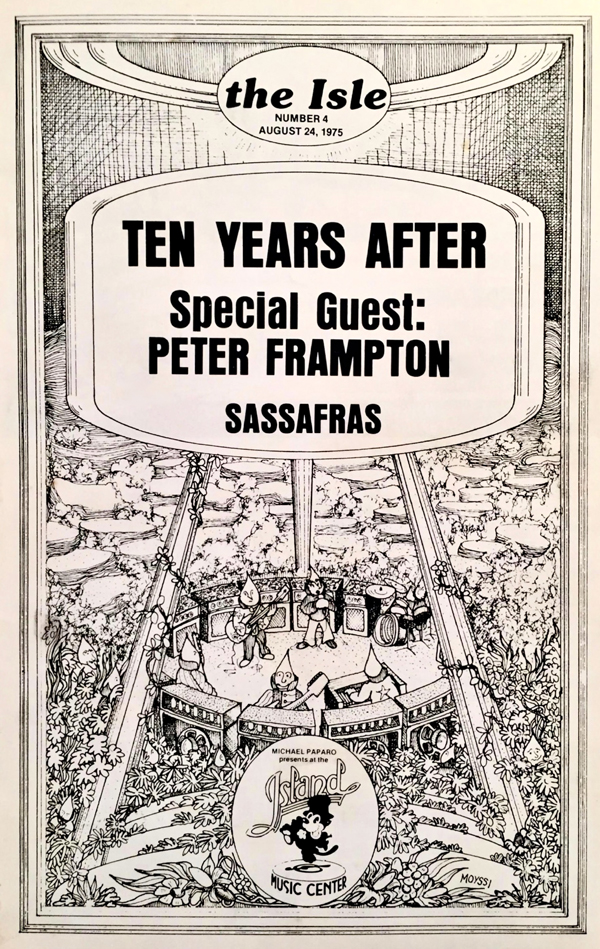

Ric of Ten Years After Returns: 1975 Newspaper Article

From the country that helped

produce Alvin Stardust and Paper Lace comes yet another

group now internationally renowned – Ten Years After. And

drummer Ric Lee, one of two members of the group born in

Mansfield, recently returned to his home town to give an

exhibition of his drumming ability at the Swan Hotel,

Mansfield. Ric aged 30, now lives in a large house

standing in a leafy 20 acres in Kent, and he made the trip

up to Mansfield to Promote Premier Drums in a

demonstration organised by the Carlsbro Sounds Centre Ltd.

Station Street Mansfield.

Ric performed a self penned drum solo and spent a short

time signing autographs and answering questions. Ten Years

After is comprised of Ric Lee, Alvin Lee, Chick Churchill

and Leo Lyons, who is also from Mansfield. Last week the

group gave a concert in Sheffield, after which they left

for a tour of America.

|

|

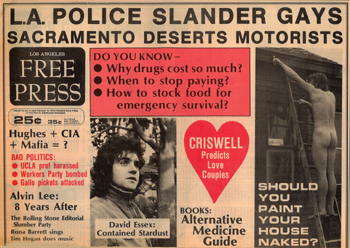

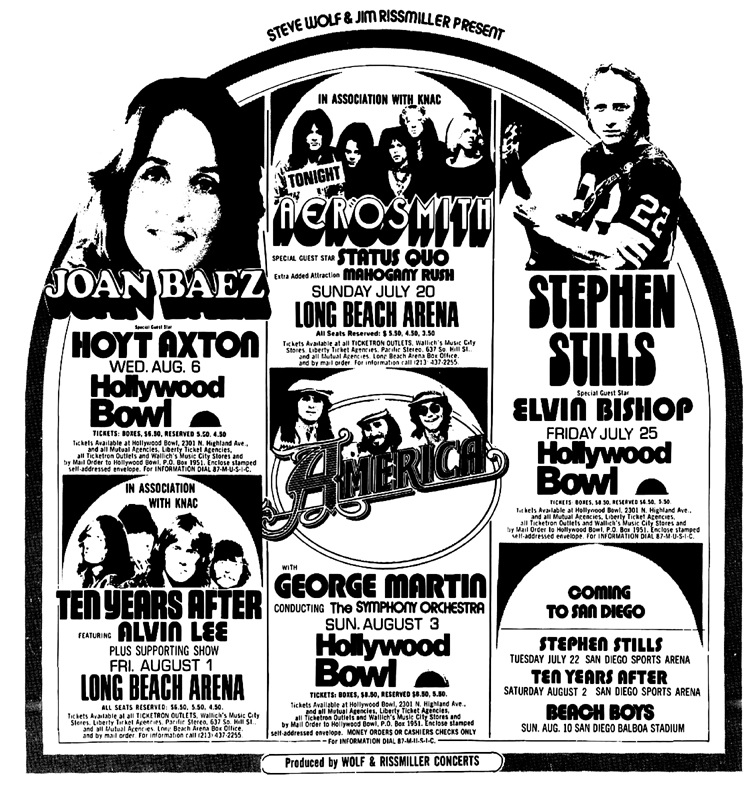

February 14, 1975

- Los Angeles FREE PRESS

By Tim Hogan

Ten Years After

never made it to the ten year mark! The results of Ten

Years After’s eight year tenure as the foremost British

boogie-band are in, and history may well record them as a

rock `n´ roll tragedy. “The kind of music we were playing

became a trap,” says Alvin Lee captured for a brief

interlude during his extended debut, U.S. tour as leader

of Alvin Lee and Company. “It got to be a trap right after

Woodstock. The movie made “I’m Going Home” too big for its

own good. It put too much weight on that aspect of the

band, until that became the only aspect of the band.

People expected “I’m Going Home” and boogie-boogie and

bash-bash”. The Woodstock movie, with it’s lengthy segment

of Lee sensually squeezing elongated chop – riffs from his

guitar catapulted Ten Years After into the ranks of

superstardom.

But Lee, the only

surviving member of the band musically, found that aspect

of music’s rewards to be frightening. It drove him into

being a recluse. “I could never play the part,” said Lee,

as he disappeared into the comforts of his baronial

mansion in England’s Berkshire countryside. It took the

renewal of Lee’s friendship with Mylon LeFevre, a

southern-fried gospel major, to lift him from his self

styled pit of depression. “Mylon sort of gave me the

gospel, in that he told me that I had a talent that I

should be using. The result of this rekindled fire was the

Lee – LeFevre album called, “On The Road To Freedom” 1973,

which did more for bringing Alvin back out into the world

than it did in the category of record sales.

The album,

featuring Lee in his first dose of acoustic country styled

music, was an instant sleeper; straight into the bargain

bins it went. “The thing was, I was trying to change with

the same influences around me. Working with Mylon, gave me

new influence and the ability to change a new environment.

I learned to enjoy the challenge of change”.

But business

before pleasure, and we soon find Alvin Lee trapped into

more Ten Years After records and touring, and last year’s

May Ten Years After tour drove the point home with

vengeance. “I remember one small incident that really

stuck in my mind. There was a black couple, about eight

rows back in the middle of the audience, really getting

off, I kind of play to them in a way. I was really

grooving on it. And then came “I’m Going Home” and the

whole crowd sort of rushed the stage, and this guy’s chick

was knocked on the floor and he had to fight for his

chick’s life. And I figured he probably wouldn’t ever come

to a gig like that again, as much as he likes the music,

because of all the hassle”.

Ten Years After

had it’s own identity to cope with. “I always thought of

Ten Years After as four people who almost fought together

to make music. It was really violent and driving, and a

lot of people do like that. In fact, I like it myself, but

not all the while. The worst thing about Ten Years After

was they didn’t have any enthusiasm about playing. It was

just a job”.

It took a dare

from George Harrison’s aide-de-camp, Terry Doran, to get

Lee back into the music world after that last Ten Years

After tour. Lee had again retired and was one day sitting

around the Harrison homestead, when Doran challenged Lee

to get off his ass and do something. “I can do whatever I

want, when I want,” said Lee. “No you can’t” teased Doran,

and Lee retorted, “Yes I Can” back and forth until Lee had

committed himself to doing something. The result was much

like the initial indications on a seismograph that

something big was coming. Four weeks later, Alvin had

drawn together some of the best available musicians under

the banner, Alvin Lee and Company. A date at London’s

Rainbow Theatre was booked and once again Alvin was out of

retirement. The concert was recorded and released as Lee’s

latest Columbia effort, “In Flight”.

The momentum from

that concert resulted in Lee agreeing to take the company

out on the road, and its been one hell-of-an experience

for Alvin who was a prisoner of his own imagination. With

slightly altered personnel from that on the LP, Lee hit

the road in January on a tour that’s been extended several

weeks because of the high level of enthusiasm that the

band has met with, and this new unit is no rehashed Ten

Years After.

“This band is a

funky band,” explains Lee. “What we’re after now is to do

some acoustic numbers, some jazz numbers, basically to add

some depth to our performance. I can nip in and nip out, I

don’t have to keep playing rhythm all the time. There’s a

lot more variety and I think it will appeal to a wider

variety of people. The music is changing and so am I”.

And Doran’s

challenge to Lee has resulted in Lee coming out more as a

musician. Early this year, he found himself in Nashville,

working with Earl Scruggs on his anniversary LP, along

with Charlie Daniels, Billy Joel, Tony Joe White, The

Scruggs Brothers, Reggie Young and Bonnie Bramlett.

Another LP with Mylon is tentatively set for some time in

1976, and he expects to return to England at the end of

this tour. And Doran’s

challenge to Lee has resulted in Lee coming out more as a

musician. Early this year, he found himself in Nashville,

working with Earl Scruggs on his anniversary LP, along

with Charlie Daniels, Billy Joel, Tony Joe White, The

Scruggs Brothers, Reggie Young and Bonnie Bramlett.

Another LP with Mylon is tentatively set for some time in

1976, and he expects to return to England at the end of

this tour.

The door is open and Alvin Lee is walking tall. “Win or

lose, I’m enjoying it”. |

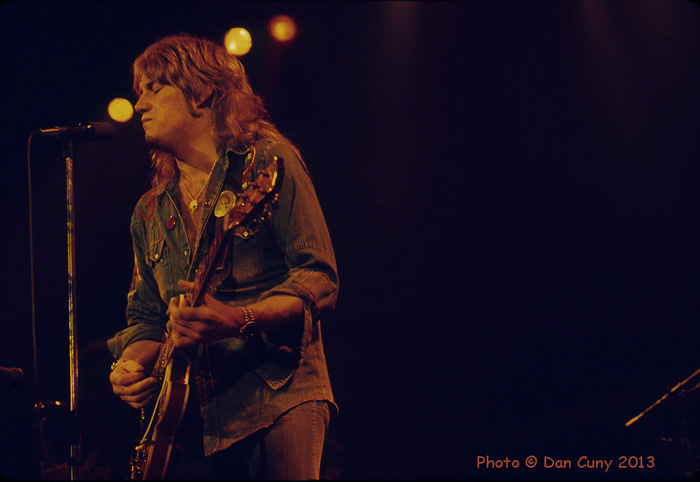

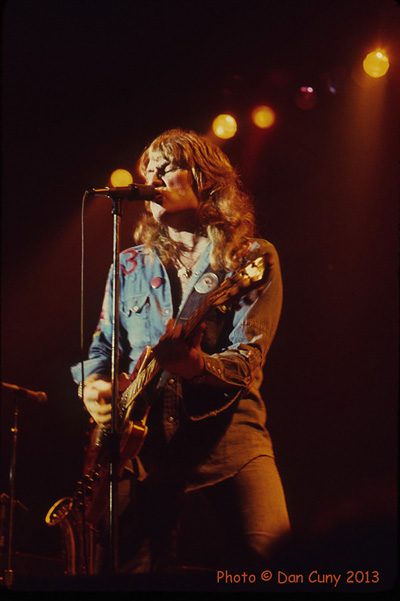

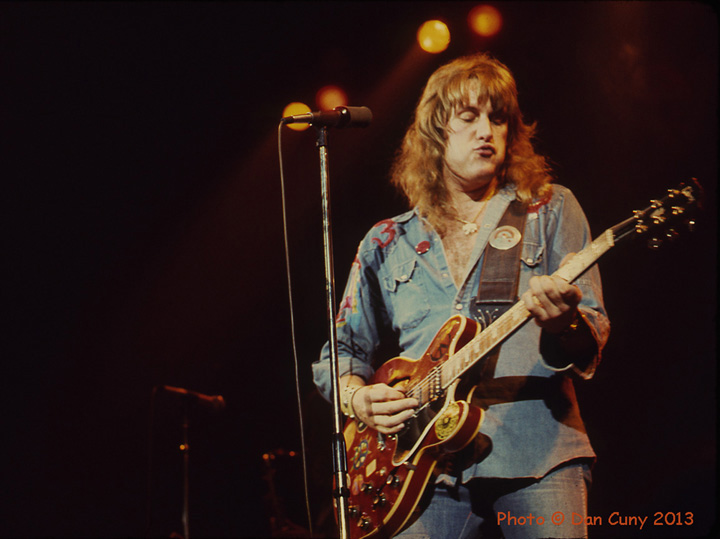

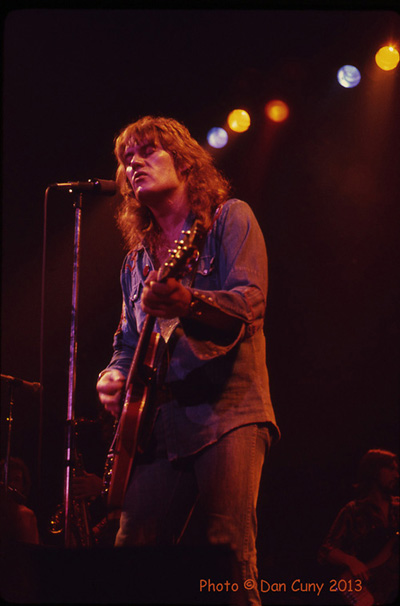

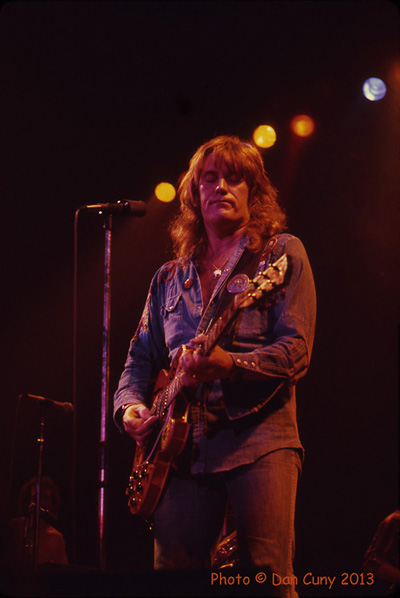

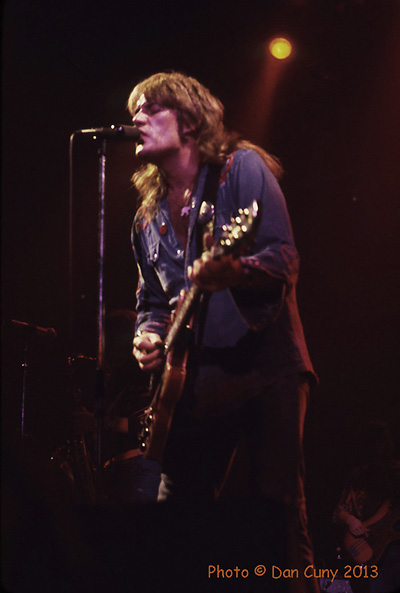

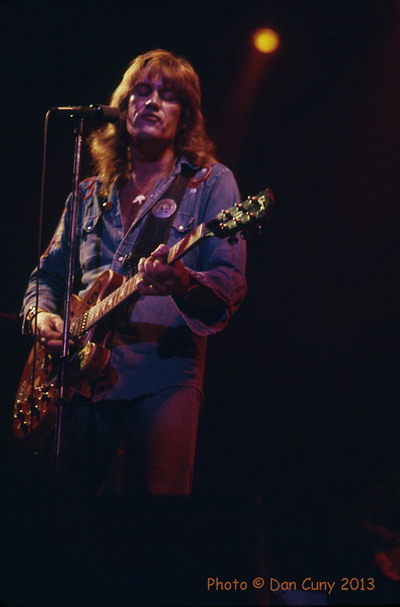

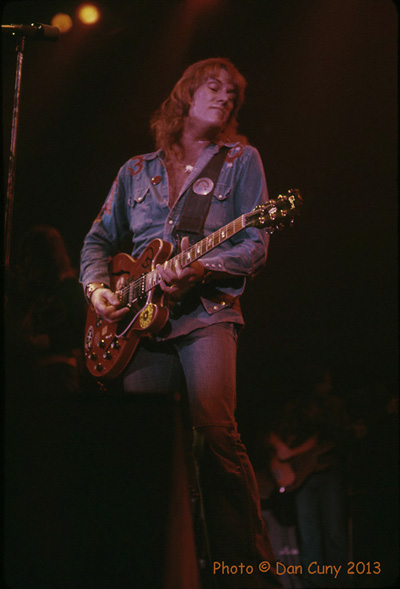

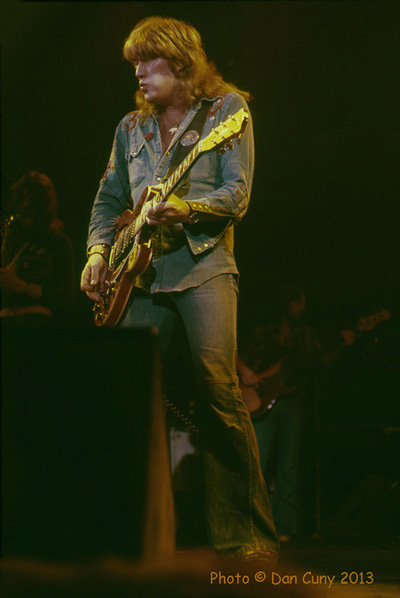

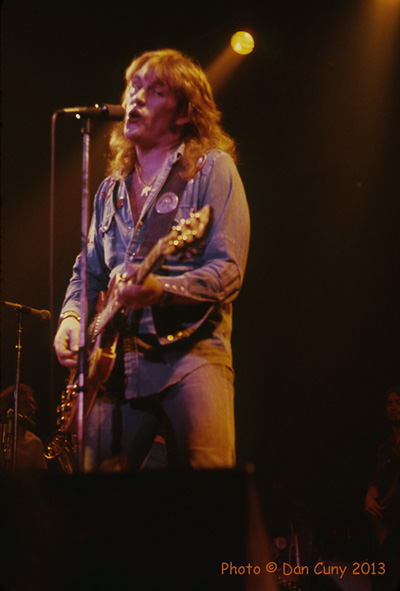

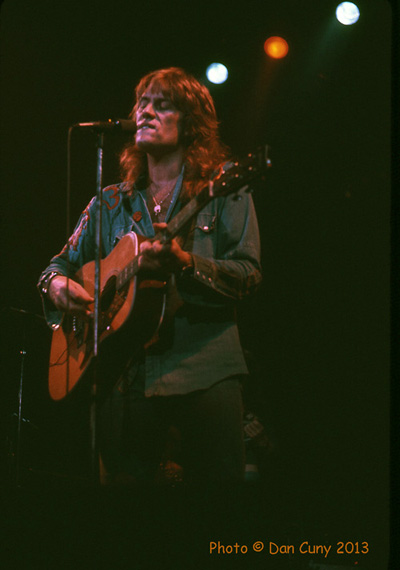

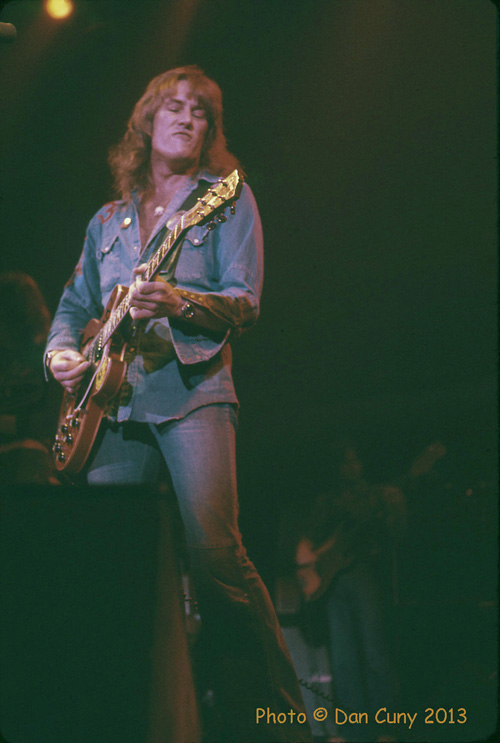

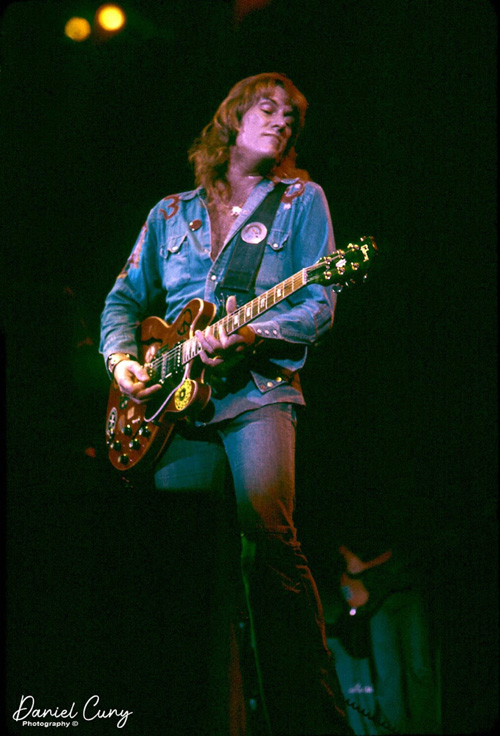

1975, February 14 -

Winterland, San Francisco

Alvin Lee & Co. - Photographer:

Dan Cuny

Photos by Daniel Cuny - Website:

https://www.dancuny.com

BRAVO Magazine - March 6, 1975

|

Many Thanks to

Claudia Staehr for the above article (Herb Staehr's

collection)

|

|

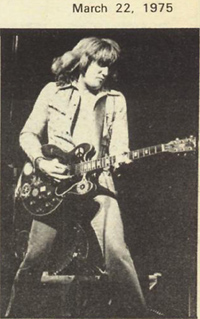

March 21, 1975 -

Alvin Lee & Co. at TV Show "Midnight Special"

NBC

Studios, Burbank, CA

Photo: Jon Levicke

21 March

1975 - Alvin Lee & Co. at "The Midnight

Special" TV Show

|

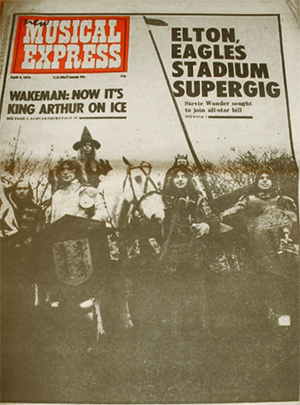

New

Musical Express

March 22, 1975

Alvin Lee is continuing to work as a soloist, while

Ten Years After remain active, and this week finds him

on the road undertaking his first ever British tour with

his own band. With a line up comprising former members

of Stone The Crows – King Crimson. Alvin Lee &

Company have dates during this gig period at Dagenham (Saturday)

and Hemel Hempstead (Sunday)

|

|

Melody Maker -

March 22, 1975

"Going Home No More" - by Chris

Welch

Alvin Lee is getting into self-sufficiency. Along with

many fellow Britons, alarmed at the daily news, he is determined to make full use of the land.

“Yes,” says Alvin peering through the windows of

his mansion at rain swept acres, “we’ve increased the size

of the vegetable garden, ready for the revolution.

We’ve got broccoli, parsnips, peas, potatoes …” It must

be wonderful to bathe hands in the soil and be one with

nature. “Oh the gardener does it. I just watch it happen.”

Disappointing, but to be fair, Alvin has most of his

time cut out in bringing rock and roll to the world, which

leaves little opportunity for raking soil, barrowing

muck or dividing rootstocks.

ABRUPT: and Alvin has been a busy man since the abrupt

change in his musical career just under a year ago.

Mention Alvin to fellow musicians, and you’ll get a

stock response; “Good Lord is Alvin STILL playing ‘I’m

Going Home?’ The answer is ‘no’ TYA is behind him,

and Alvin,

Guitarist and Pioneer has replaced Alvin,

Man In A Rut. It was not without opposition that Alvin

took the gamble that led to the end of Ten Years After. He

says, quite honestly , that in the final days, only

money held the old band together, and of course his Management were not to keen on him throwing away what

they may have regarded as a sound investment.

There was doubtless a certain amount of wailing and

gnashing of teeth in the corridors of power, when Alvin

flung in his lot with the likes of Mel Collins, Tim

Hinkley and Ian Wallace, leaving out in the cold Chick Churchill, Ric Lee and Leo Lyons. As the dust settles

still, it is possible to perceive that while TYA are no more, and Alvin has severed some of his ties with Chrysalis,

the guitarist is determined to broaden his horizons, and stay at the forefront of musical

events.

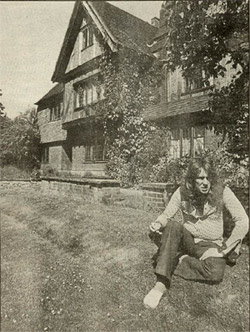

Alvin’s acres are situated in rolling countryside,

not far from George Harrison’s palatial home. The latter is

surrounded by lodge houses and high walls and looks not

unlike one of those mid-Victorian establishments designed to bring 19th century enlightenment

to the insane.

ABODE: But Alvin’s pad has a friendly air of a

gentleman farmers abode. And indeed it was such a place, when

over a thousand acres fell within its domain. So

important was its role in the community, that it served as an

air raid warning station and water rate collection centre, until most of its land and assets were stripped away

and finally a rock and roller from Nottingham took over

where once Squires held sway.

The slight air of decay is heightened by the area of

devastation that was a milking shed and indoor tennis court,

which recently collapsed during a storm. “That’s

what comes of living in big houses,” says Alvin

phlegmatically. But what will future tenants make of the vast recording

studio Lee has built in the Tudor barn, I wondered. Master

Lee may have little inclination towards agriculture,

but he is certainly not idle. He has just returned from the Americas, and a successful tour with his new band

(known

as Alvin Lee & Co), when we met in his lounge and discussed pertinent

matters.

“I got back a week ago and we finished off the tour

in Honolulu. We spent seven weeks on the road and it was very

interesting. First of all we played Europe and

Scandinavia. We played one gig in Paris and just before

Christmas, we played some dates in Germany. “Worried? No not

really. The reaction in Germany told me we were onto the

right thing, although the Scandinavian audiences were a

bit strange. But I think that’s peculiar to Scandinavia.

They’re not so in touch with world musical developments. I got the feeling they didn’t know what to

make of us. That was one place we suffered from not being like Ten

Years After. “In Germany if felt more like we were doing

a show. At first it tended to be just a list of

songs,

y’know? It really came together in Germany, where we played

at some American bases, and that made us feel

optimistic about playing in the States. “I was worried there

would be shouts for ‘I’m Going Home’

but there wasn’t a lot of that. In the first fifteen

minutes we established that this was going to be a different band and audiences seemed

rather stunned. We played mainly 5,000 seaters and a couple of big

ones. The people came to listen and

realised it wasn’t just a rock and roll extravaganza. The

atmosphere was more intimate and controlled, without

people rushing to the front of the stage.”

Did all the guys in the band enjoy the experience?

“Yep. There were eight of us stuck together for seven

weeks, and we’d not worked together before. There were a

couple of gigs that weren’t up to standard, but one thing

I’ve learnt after eight years on the road, is not to get

upset about good and bad gigs, because as long as the general

standard is high, audiences won’t worry.

BUSINESS: “In

fact the audiences were great, and only on the business side,

were some of the promoters worried.

Some people thought it wasn’t Alvin Lee without

TYA---they thought it might be somebody else using the same

name! “We did some places I’d not played before, like Knoxville Tennessee, and it was a good

experience, for the band got better and

better. And what had been

an experiment for me before Christmas, has now become my definite

direction. I wasn’t sure until the tour, but

I really got off on it.

|

I would have done ANYTHING to get out

of the rut. “The vibe I got back was that we were

playing to the people, rather than presenting a hypey,

superstar bit, and a lot of people approved of that. A lot of

silliness goes on in the world of groups, and it came across

that we were taking the music seriously. “

A lot of people

coming to see what we were up to, were turned on by the new

stuff. They liked the percussion duel between Ian

Wallace and our conga player, Brother James, and Mel Collins sax

playing. “One

of the highlights of the trip to the States for me, was a

session I did in Nashville with Earl Scruggs. It’s his 25th anniversary with

Columbia and they called me up to help out on a celebration

album.

|

|

FIDDLE: “There was Charlie Daniels the fiddle player

and guitarist and Reggie Young, who it turned out I’d heard on so many

records. I’d always liked his solos

and never knew who played them. He was on Bill Dogget’s

‘Honky Tonk’ and Billy Swan’s new LP.

“Let me see---Tony Joe White came down, and part of

the Marshal Tucker Band. It really was a party. Everybody arrived

very late, and I was all early and businesslike. I asked

Earl Scruggs what he wanted to play and he said: ‘Ah

don’t rightly know!’ “But we did four tracks on one

session, then I went off and did a gig, and came back

for some more sessions, this time with Aretha Franklin’s

keyboard player, and Willie Hall who was the drummer on

the original ‘Shaft.’ He was steaming. “I don’t know

when the album’s coming out or what it’s called,

but Bob Johnstone produced it. We got on so well I wanted to

invite them all round to my place and make an album. We

could call it ‘Nashville On Thames.’

“I also did a Bo Diddley session in New York, with

Leslie West and myself on guitars, and Carmine Appice and Tim Bogert as the rhythm

section. We did all the

old ones like ‘Bo Diddley Is A Gunslinger.’ I just turned

up and blew, and it was great. No, I couldn’t get any of

the tapes I’m afraid! ”

HATE: Alvin admits that launching his new band was like

starting again: “But we started on a good level, headlining at 6,000 seaters and I like

working. Hate

days off. I’d sooner be playing every night. The nice thing was that people accepted us and we didn’t have

to play any old numbers at all. “With TYA they always shouted for the stuff they

knew. The LP we did live

from the Rainbow sold well in America, about 100,000

but it only sold 8,000 in England and I was

disappointed about that. Perhaps if we had done a tour here,

it might have helped. “We’re doing some dates now, not a

major tour, but some universities. I’d sooner do that than

concerts with all the teeny-bops and teddy-boys. We

want to play to a listening audience. We’ll be working until the end of March and then it’ll be pretty

loose. “It’s nice. There’s no pressures. We just blow

and have a good time.”

Will there be another LP from the group? “Well there’s not another release planned until the

Autumn. I want to do some new things and may not stick to the same line-up for

recording. We’ve been leaning

a lot towards jazz, under the influence of Mel and the bass

player.

FREEDOM: “That’s just the way it worked out and it

wasn’t intended. I believe in giving musicians freedom,

although the business element believe I should dominate

and come on strong. I just enjoy being a part of the band.

It’s not really my music, but I’m adapting to their

style. “It’s a very funky rhythm section, which isn’t

exactly my style, but it’s taught me a lot of discipline. Ten

Years After was one long raving solo, but with Mel blowing

away, I and afford to lay back.

“I love his playing and he’s been getting great

reviews.

And Ian’s drumming is so dynamic. He’ll drop the level right down into

another groove, and he’ll do it anytime, so you have to

watch for the signal. A couple of times he’s left me

wailing up there on my own! I’m adapting to it, and it’s

good for me musically. “If Mel solos first and I follow, then

I have to pull my licks together, because he’s

phenomenal. He can play ten times faster than me, and

with such light and shade.”

Has TYA definitely broken up---officially? “It would appear so. I’ve not heard a word from

anybody since last May. But I keep getting bills. It’s a

shame ---it seems to have dwindled to nothing. We were never

a great musical band as such, but it had energy. When the energy faded it left a successful

shell, without

any meat. “I

hear Leo is now managing Wessex Studios, and Ric has got an LP

together, but I’ve not heard

from any of them. Mind you, it had been like that for some

years. We never spoke to each other except during the tours. If you have no mutual interests it’s got to suffer

sooner or later. “Maybe we’ll get back one day, but

the only thing that kept TYA together was money, and that’s

not the right motivation. It had been like that for two years. We had been together for eight

years. We nearly made it to ten.”

|

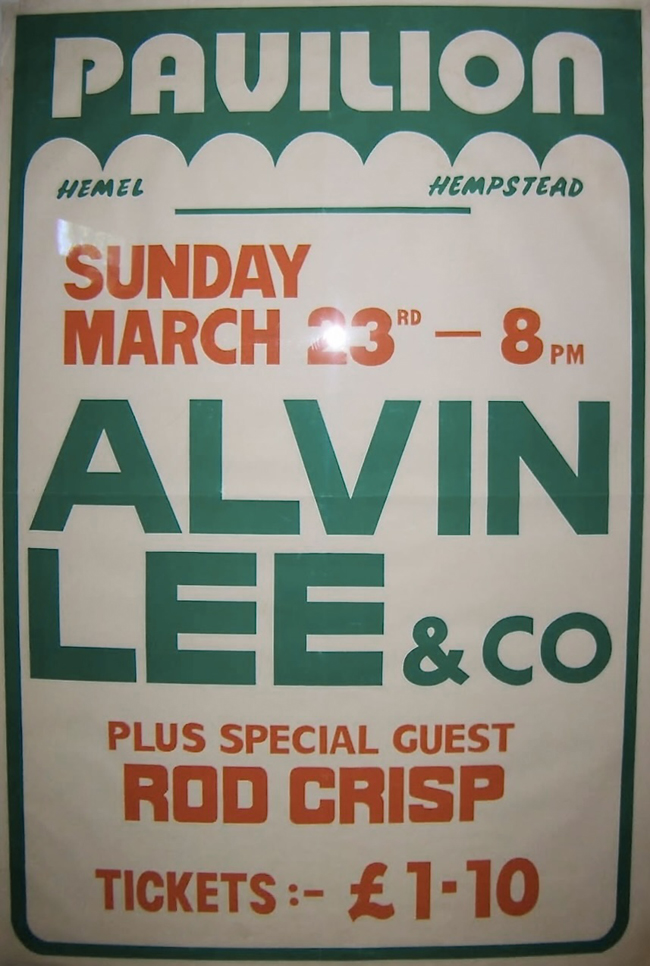

1975, March 23 - Alvin Lee & Co. -

Hemel Hempstead Pavilion - Concert Poster

|

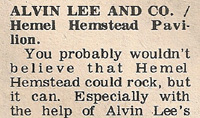

RECORD MIRROR -

March 29, 1975

Alvin Lee and Co.

Concert Review

Hemel Hemstead

Pavilion (Sunday Concert)

You probably

wouldn’t believe that Hermel Hemstead could rock, but it

can. Especially with the help of Alvin Lee’s new band

and a mixture of new songs and old rockers. The band, a

six piece blend of old Stone The Crows and King Crimson

members, are individually proficient, but took a long

time to bed in together. So it wasn’t until the later

reaches of the set that things started to move. Having

just returned from America and now filling in time on a

few UK dates before recording their first album, the

band as a whole are warming themselves up, getting to

know each other. They’re well on the way, though not

quite there yet. Though numbers like: “Keep On Moving”,

“Got To Get Back”, “Somebody’s Calling Me”, even

“Freedom For The Stallion”, the quality of the musicians

over came any hint of

un-togerther-ness.

The atmosphere on stage was loose, joking with each

other and generally at ease. Mel Collins sax was

featured heavily, and though he is an outstanding

player, one felt a lot more tracks might have featured

more of Lee’s guitar. When it did appear, so did the old

magic. Sad thing was, it did not appear for any length

of time. By the time of the encore:

“Every Blues

You’ve Ever Heard”, and “Ride My Train”, the audience

had gathered round the stage and were shaking and

dancing where appropriate. Yes, they’re a solid band

alright, just a bit new at the moment, which promises

well for the future.

Article by Martin Thorpe |

|

New

Musical Express 4/ 5/ 75

THERE’S

A WHOLE WORLD OF LICKS OUT THERE:

AS ALVIN LEE becomes musically more itinerant in the grand

tradition of the Disillusioned Rock Star nonchalantly wandering in and out of

projects, it seems his

saga is becoming correspondingly less impressive. Even now, several years after what the hulky AL describes as

“my first move away from neurotic rock” (when

he recorded the album “On The Road To Freedom” with Mylon

Le Fevre between appointments with Ten Years

After) he is considering ceasing operations with the present

band, Alvin Lee & Company. “As far as this band goes

we only plan to work till the end of March, then it’s back

to the studio. Back to the drawing board,” he explains.

You might say Alvin lays it on the line in a sometimes

humorous, often honest, and generally engaging way.

The Most Boring Man In The West must surely be a reference to

his guitar playing, and not his conversation.

And just in case you’ve as much of an aversion to Alvin Lee

Interviews as instalments of Crossroads we’d better fill in a few biographical details to bring you up to

date.

Musically speaking, Lee was born in the late 60’s and

remained as the head of the Ten Years After household

until 1973 when, due to spiritual disenchantment, he buggered

off with the aforementioned Le Fevre. “It was the first time in four years I was coming out of the studios

overjoyed with something I’d done.” He comments. “And

it gave me the energy of my younger self. I realised I

wasn’t really getting old, I was just getting in that rut,

and if

I got out of it and did things—it’d keep me going.”

Obviously delighted with the experience and excitement he

encountered once out of the traditional confines of a stable

unit, he started to poke the neck of his Gibson 335 into

alien areas. With Boz Burrell, Tim Hinkley, Mel Collins and

Ian Wallace he formed a band called ‘The Gits’ “a funky kinda

thing, not unlike the Average Whites”. When

Boz split for Bad Company they disbanded, making

way for other musicians to enter Lee’s life, such as Alan

Spenner, Neil Hubbard and the Kokomo singers.

Their Rainbow gig was recorded (“In Flight”) and filmed

and marked the conceptual debut of Lee & Company.

Changes ensued: Wallace and Collins stayed but the rest of the

band now consisted of Ronnie Leahy, Steve Thompson, and percussionist Brother James. Earlier this

year they toured comparatively small theatres in America and more recently played British

Universities.

From the States dates Lee came to two distinct conclusions;

because the smaller theatres were “a strange environment” the security forces were totally able to

control the audience and so prevent a suitable ambiance in

the music. In fact, only six of their dates really impressed

him. So next time round he intends to “strike a medium” between the low and high venues. Secondly; the band wasn’t all it should be. “I think where

it felt short—well, in some places it didn’t, it was great

but elsewhere it was just a bit cold, a bit sessiony.” he

remarks. “I get it too. If I’m playing and I turn round on

stage and see everybody getting into the thing, but not

getting off visibly, I’m not suddenly gonna get off and

start leaping around, because I’d feel silly. “If I turn

around and see, like Leo” (Lyons of TYA) “for example

who’d always be thumpin’ an’ thrashin an’ sweatin’…..that

kinda gives me a kick.

“So I wanna go in the direction of keeping the musical taste

I’m getting into, but produce a bit more kick and a

bit more balls. That’s what it needs. In this band I’ve

felt that the climax comes too late and too quick.”

Alvin does not, however, lay the blame totally on his band. He

mentions one problem that he still suffers from;

the reputation of being “a rock ‘n’ roll, boogie-woogie,

rave up-type guitarist”. Consequently audience response comes on what he calls “a trite three chorder”, rather

than on, say the modern jazz which had preceded it. “There

again,” he says, defending his boogie-woogie image, “when

I get out on stage and I feel that vibe I actually want to do it. If the audience wants to get rockin’, I dig

playing like that. “It’s just that this band is almost too

tasty to rock ‘n’ roll with effect. “It’s so tight,”

he elaborates , “that it gets boring quicker than if your

playing with somebody who’s feeling something, and maybe they….uh…over

feel and go off. But you get these new changes and new things

happening. “I’d really like to look

for some fresh musicians.”

But what is Lee attempting to do with the Company bands? His

attitude to do this particular project seems

ambivalent. It appears he’s attempting to form a unit of

which he could be a mere part, in a similar way to

what Clapton did with the Dominos. Yet he still wants to

remain the front man.

"It really wasn’t meant to be,” he says emphatically,

“but that’s the way it turned out. When you do the singing

and the guitar playing you tend to be the front man rather

than a musician.” And he adds that, at a recent jam session in Dingwalls with Carol Grimes and others, he

particularly enjoyed standing by the speakers just

playing guitar. “I think with the right people I could do

that.” He continues, “Jimmy Page is just a guitarist, but it’s his band, his direction, but he has Robert Plant

dealing with the sexual image and the fronting, which is great, because that’s something which has always made me

feel awkward, ya-know? “I really would like

to be….I already think of myself as a guitarist. I don’t

think of myself as a singer. I just kinda do that

adequately enough. I’m not a phenomenal singer, I don’t

have a voice that’s recognisable like say Rod Stewart.”

Of course, another consideration on this point is that Alvin

Lee controls the purse strings, and so pays the guys

a wage, which immediately creates something of a gulf between

them. (And it’s also feasible that his ego prevents

him from theoretically lowering himself to an equal status

basis within the outfit).

“Unless it is a band of people that I could feel on a par

with musically.” He explains “it couldn’t really be an

equal

situation, because as I say, if I go and do a tour at the

moment as Alvin Lee & Company, people come see me and

what the Company is. It’s not as if the Company itself is

drawing people in. “It could do, if I continued to work it,

but I’m not going to get a band together and stick with it

because that would become the same kind of trap as Ten

Years After got into—and probably a lot quicker, because

I’ve been through that scene.

“I enjoyed it,” he hastily asserts, “but all the bands

that stay together a long while seem to go in that direction.

It

turns into A Job. Tours turn into a “How much do we get?”

That’s the wrong motivation for going out to play

music, just to make a few bucks. “I’m not against making

bread, but I’d rather get something I’m proud to be

with and then work out how to get some bread out of it. That

seems more like the right way of going about it.”

ALTHOUGH Lee will retain those musicians from the present band

“who’re really keen” he now intends to find

some fresh faces on the English scene, and move into various

musical styles, which may be reggae, blues or even

jazz. Whatever turns him on. “What I intend to do is try

different things out,” he says. “I’m looking for

different musicians with different influences, ‘cause what I’ve

found is, different musicians around me with different influences

make me look for new styles. “Besides, I think there are

good musicians in England. But the scene

has

got so poppy again. It’s gone round in a circle. There’s a

lot of good musicians who resort to playing

something

really corny just to get something going.” He should know.

“A lot of bands that you see backing up

singers

and duets on TV have got good musicians. It’s just that

they’re stuck in a rut. “Everything’s an experiment.

I don’t really feel anything that strongly urging to come

out…except to try new directions. That’s

the

only real urge. “The most commercial thing for me to do

would be to get a four-piece rock band.” He points

out.

“I mean, the most commercial thing for me to HAVE DONE when

the TYA thing was DROOPING

would’ve

been to get three more musicians, keep the name, and go out

and rock ‘n’ roll. “But, as I say, my own

head heeded to go in these other directions. “I don’t want

to go out on the road for the sake of doing it, I

want

to have something going to take out and show the people. Which

is what I’ve done with Company. “It’s

been successful.”

WITH

ALVIN spieling so candidly it’d be remiss not to bring up

the subject of TYA---remember. Of course what

it’s

not in vogue these days to announce the fact when a major band

splits up. So, like the Moody Blues, TYA

is

“inactive”---only because nobody will say, Yes folks,

we’ve split. Which of course, is something of an

advantage

to us, because---if ever the situation did occur---we won’t

have to suffer an exhaustive campaign announcing

a reformation. “It’s DEFINITELY FINISHED.” Says Lee,

“because no one will say it’s finished.

But

as yet I don’t see any move to get it together. The only

reason they or I would consider it boils down to

the

money again. “I’m sure everybody’d ring up and say,

‘Let’s do a tour and make a few thousand’, but nobody’s

saying ‘I really want to play’.”

Alvin

considers the high point of TYA was when they played the

Marquee. “We Kicked Shit. Sweat and grind.”

he recalls, “I really used to get emotions in those days.” Even

so he is reluctant to deride their music towards the end, and

explains numbers such as “Goin Home” were

musically

good---“because we’d played them 8,000 times.” But their

career followed the pattern of so many

successful bands. Once they had financial stability their interest

diversified, and touring became a monotonous process.

Their motto, Lee remembers, was “Get on, get off, and go

home.” And for the last two years it was a

thoughtless process. “I could be up there playing what appeared to be an

incredible solo to the majority of

people.”

says Alvin, “but in fact I was probably thinking about

something else.” Like?

“Looking round the audience and

seeing who’s there and things. Checking out that scene,”

he smirks, “was always one of the sidelines.

Sometimes

I’d just wander off totally. “It’s like when you’re

driving a car, you’ll be thinking about something else,

and then suddenly you’ll come back to driving, and you

realise you’ve just driven through London, down

the

M4 and turned off, but you don’t remember a thing about it.

“Well when you repeat yourself playing the same numbers

you just play on automatic.”

And

the analogy he uses to explain exactly why he is now

experimenting in music is as equally, er, illuminating.

“It’s

like an old tired marriage a lot of the time. Nothing gets you

off more than a bit of fresh on the side. That’s really

the basis of what I’m doing---just looking for that fresh

excitement. Trying to renew the energy I had before.

“It’s working. “As long as it’s good it can go in any

direction,

from blues, jazz. Rock, reggae, classical, musique concrete,

to whatever. My gig is to make it good, and enjoy doing it.

“There’s a whole new World of licks and

tricks

to experiment in.” “Looking round the audience and

seeing who’s there and things. Checking out that scene,”

he smirks, “was always one of the sidelines.

Sometimes

I’d just wander off totally. “It’s like when you’re

driving a car, you’ll be thinking about something else,

and then suddenly you’ll come back to driving, and you

realise you’ve just driven through London, down

the

M4 and turned off, but you don’t remember a thing about it.

“Well when you repeat yourself playing the same numbers

you just play on automatic.”

And

the analogy he uses to explain exactly why he is now

experimenting in music is as equally, er, illuminating.

“It’s

like an old tired marriage a lot of the time. Nothing gets you

off more than a bit of fresh on the side. That’s really

the basis of what I’m doing---just looking for that fresh

excitement. Trying to renew the energy I had before.

“It’s working. “As long as it’s good it can go in any

direction,

from blues, jazz. Rock, reggae, classical, musique concrete,

to whatever. My gig is to make it good, and enjoy doing it.

“There’s a whole new World of licks and

tricks

to experiment in.”

Article

written by

TONY

STEWART

|

|

From Rolling Stone Magazine 4/ 10/ 75

Alvin

Lee - "In Flight" (Columbia PG 33187

)

British

blues has always been a workmanlike form, as much a job as

a pleasure. Alvin Lee is smart enough to

realize this, and having deserted his own limey blues band, Ten

Years After, he has made In Flight in pursuit

of a new image. Unfortunately, Lee’s problem isn’t

easily wished away. He sinks into new restrictions

quicker

than he can soar away from the old ones.

Ten

Years After was never much of a group, although they made

some interesting records, particularly

Ssssh

and Watt. The group was the sleeper surprise of Woodstock,

and “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl”

and

“I’m Going Home” were significant pre-heavy metal

tours de farce for guitar.

All

of their exciting moments, though, had as much to do with

stagecraft as music. Lee’s flashing smile was as

important

as the white heat of his guitar runs. Alvin Lee was fast,

the epitome of the British speed demon

guitarist,

but his speed and his smile were intertwined forever.

The

one made him saleable, the other made him identifiable; I

was never sure which was which, but we

all

know what too much speed does for the teeth. Still,

without those alabaster incisors, Ten Years After

might

have lent new meaning to the concept of facelessness which

dominates so much of the rest of British blues.

For

all its limits, Lee’s twin talents gave them a head

start over the various Foghats, Savoy Browns and Mayalls. Lee

has personally, if not charisma, and the sense of

humour--not just fun, which is intimately tied to work—

that

ought to go with it. It is difficult

to imagine even such an inspired British bluesman

as Eric Clapton

having

the ironic self-perspective to tote a watermelon over his

shoulder as he trudged off the Woodstock stage,

in full view of 500,000 fans and half as many cameras.

Lee

is in flight, in deed as well as concept, on his new album.

Fleeing that confining image, however, he seems

desperate,

uncertain of just what he’ll choose to replace it with.

Consequently, In Flight is a kitchen-sink job;

a

live album, two records, with horns and a female chorus.

The music can’t decide between rock and blues

and

half-assed mellow jazz. There isn’t a chance for any of

the facets to shine long enough to give the record,

or

Alvin focus.

Lee’s

best moves are as a rock & roller, even if his most

coherent ones are still tied to his version of the blues.

The

most interesting track on the album, “Mystery Train,”

fails utterly. After Elvis Presley’s and Junior

Parker’s

versions,

“Mystery Train” wasn’t a song anymore at all; it was

a pair of records, each defining the limits of one

of

its dual themes (sex and death). Lee has nothing to add to

that except a pleasant, smoky voice. But even

that

voice is obscured by the awful chorus. The English have

been trying for a decade to figure out what to do

with

the Stax concept—the way voices and horns are used in

Memphis—without much luck. Lee’s ideas

aren’t

much more useful than Joe Cocker’s. The chorus

shouldn’t drown out the singer in an

arrangement

like this; it should add tension. Here the chorus

elasticises everything, drawing it out to the point

of boredom. It happens time and again—on “Slow Down,”

“Money Honey,” which had the chance to be special,

even

Lee’s own best song “I’m Writing You A Letter.”

Surprisingly,

Mel Collins’s sax and flute are handled with some taste,

probably because they are not, as with most

blues

groups which resort to horns, bowled over by a blaring

brass section. (I know of no great white rock record

in

which brass plays a dominant role.) But for all their

limitations, the rock songs are still more effective than

Lee’s blues, which for the most part are just as excessive in

length and

velocity as those he played with

Ten

Years After. Only sax dipping in and out reminds that this

is not a TYA record.

With

his usual irony, though, Lee redeems himself a little,

simply by calling one of the songs “Every Blues You’ve

Ever Heard.” He ought to be required to open his show

with it as a sort of caveat emptor –and not he alone, but

the whole sorry batch of Anglo blues mummies. Still,

this isn’t as inauspicious a debut as I may have made it

seem. Lee has broken free of the TYA image,

certifying

himself as a rock singer of some talent. The rockabilly

cuts here move, and if it weren’t for the chorus,

you

could say they never get cute, as too much British

pseudo-rockabilly does.

With

a little reorganization, Lee might have a fine post-heavy

band in the making.

by Dave Marsh, music critic for ‘Newsday’

|

|

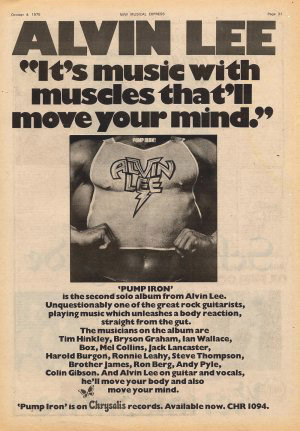

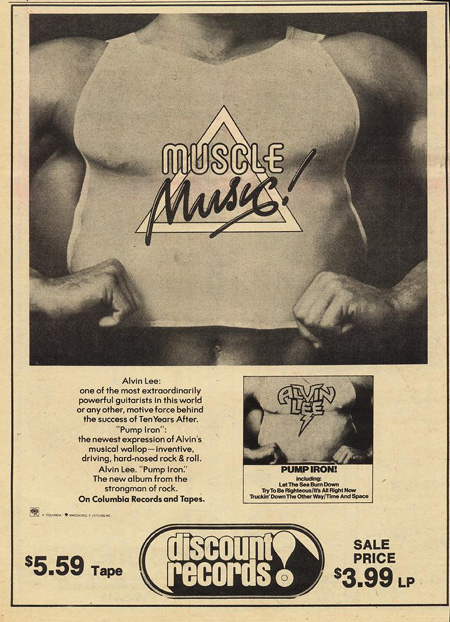

Record News: Alvin

Lee’s new album “Let The Sea Burn Down” will be

issued in mid – September by Chrysalis. Among musicians

featured on the set are Ian Wallace, Tom Bryson and Ron

Burgh (all on drums) Andy Pyle, Colin Gibson and Boz

Burrell (all on bass); Tim Hinckley (keyboards), Harold

Burgon (Synthesiser) and Jack Lancaster (sax). The set was

recorded this spring at Lee’s home in Oxfordshire.

(1975)

|

|

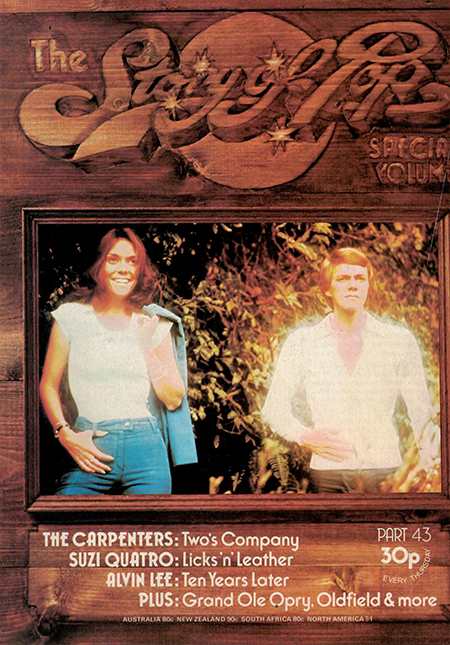

THE STORY OF POP – SPECIAL VOLUME – PART 43 – 30p – EVERY

THURSDAY:

THE GREATS – ALVIN LEE: THE AXE

MAN COMETH: 1974 / 1975

If Eric Clapton Was The First

Guitar Hero. Jimi Hendrix The Most Absolutely Crazed, Then Alvin Lee, A Guy Who Looked As

If He Came From Scandinavia, But Really Hailed From Nottingham, A Centre of

England’s Light Engineering Industry, Was The Fastest and

In Terms of Personality The Sanest. Not For Alvin Was

There Any Heavy Involvement With Dope Or Religion. If He

Experienced Any Intense Personal Pain Then It Never Showed

In His Playing. Unlike Eric Clapton, Jimi Hendrix or Peter

Green His Playing Never Sounded Totally Committed To The

Blues, Though That Was Where The Bulk of His Inspiration

Came From. Nevertheless, Alvin Lee’s Status As A Bona-Fide

Guitar-Hero Was Established By The Late 1960’s (August 1969)

Following In The Wake of Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix and

In A Way, It All Happened In An 11 – Minute Period At

Woodstock, The Rock Festival That Was For A Time Regarded

As A Turning Point For A New Generation. It Was There That

Alvin Lee and His Band, Ten Years After (Alvin Often

Maintained That "Ten Years After" Operated As A Co-Op, But

As Time Went On It Became More and More Evident That Alvin

Lee Was Ten Years After; As He Wrote All The Songs, Sang

Them, Played Almost All The Solos and Was The One That

Audiences Focused Their Attention On) – Turned In A

Rip-Roaring Piece of Rock – Blues, Short On Aesthetic

Value, But High On Sheer Flash, That Highlighted Some of

The Fastest Electric Blues Inspired Guitar Ever Played, On

The Band’s Song "I’m Going Home."

Alvin’s Appearance

Became One of The Highlights of The Subsequent Woodstock

Movie, This Is Where Alvin and The Rest of "Ten Years

After" Won Their Place In The Hearts of Countless American

Rock Fans For Their Particular Brand of Boogie. As

American Rock Fans Are Particularly Partial To Boogie and

Alvin and His Group Could Boogie Better Than Most. Hence

The Reason That They Did 28 Tours of The United States Up

To Their Farewell Tour In Mid 1975.

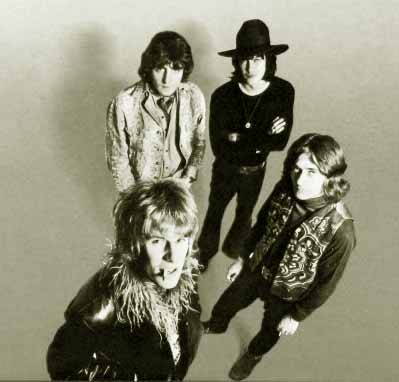

The Roots of Ten Years After

Grew From A Nottingham – Based Band Called "The Jaybirds"

That Was Formed In The Early 1960’s – The Personal At That

Time Included Alvin Lee and Leo Lyons. The Band’s Roadie

Was Chick Churchill Who, Though He Wanted To Be, and Was

Considered By The Others To Be Good Enough To Join The

Outfit, He Didn’t Have The Money To Buy A Hammond Organ,

The Instrument That He Had Been Playing, Courtesy of

Friends, For Some Time. It Was The Hard Round of Gigs That

Enabled The Jaybirds To Save Enough Money That Enabled

Them To Place A Deposit On A Hammond, and Chick Was In.

This Is When Alvin Lee Decided

To Change The Name of The Band To "Ten Years After" Meaning: "On The Grounds That

"We Started Ten Years After Elvis Presley."

If Ten Years After Had Appeared

On The Music Scene A Year Or Two Earlier, Alvin Lee

Wouldn’t Have Been Allowed / Accepted, or Given So Much

Room To Stretch Out As The Instrumentalist He Was On The

Debut Ten Years After Album – (1967).

It Was Eric Clapton and Jimi

Hendrix That Opened The Doors and The Record – Buying

Public Were Ready To Hear As Much Blues Inspired Guitar

Playing As Could Be Laid On Them. So Alvin Obliged Them On

That Debut Album and Gave The Ever-Increasing White Blues

Audience Just What They Wanted.

RARE SPEED:

Veteran Bluesman Willie Dixon’s

"Spoonful" Was Was Somewhat Daringly Included On The

Album; After All, Cream Had Turned In Their Version of The

Song On Their First Album, Called "Fresh Cream" That Was

Released In 1966. While Ten Years After’s Version Showed

That Their Guitarist Was More Than Just A Competent White

Contemporary Blues Guitarist. And While Alvin Didn’t Come

Across As Sincere As Eric Clapton, Or Peter Green, His

Playing Displayed A Rare Speed If Not Thoughtful

Construction. On Some of The Album’s Cuts This Showed To

The Extent Where Alvin’s Playing Wasn’t So Much Fast As It

Was Downright Hurried For Instance – "I Want To Know" - On

Al Kooper’s Blues "I Can’t Keep From Crying Sometimes,"

Alvin’s Playing Was Jazzier Than The Work of Other Popular

Guitarist of The Era…And It Was This Side of Alvin’s

Playing That Was Fully Explored On Ten Years After’s Second Album,

Called "Undead" – A Live Recording!

During This Time Period Ten

Years After As A Group Very Much Differed From Their

Contemporaries In Their Light Approach. Their Rhythm

Section of Leo Lyons and Drummer Ric Lee, Didn’t Make Any

Attempt At Being Heavy, Preferring to Go For An Approach

That Had Much More To Do With Swing. Alvin’s Playing

Lacked The Knife-Edge Tension of His Contemporaries and He

Preferred To Stretch Out With His Guitar, Like On The

Album’s "I May Be Wrong But I Won’t Be

Wrong Always" Which Again Demonstrated Alvin’s Great Speed

Playing. Unfortunately, He Tended To Repeat His Licks

Incessantly So That His Playing Came Across As Being

Unimaginative, Even If It Did Rate High On Flash!

Undead Also Contains The First

Ten Years After’s Version of "Goin’ Home" (It Was Later To

Appear On The Woodstock Sound-Track Album and On Their

"Recorded Live Album That Was Released In 1973). The

"Undead" Version Isn’t As Blatantly Ear-Catching As The

Woodstock Version, and Once Again The Above Criticisms

Could Be Applied To Alvin Lee’s Playing On It. Despite

Alvin’s Aesthetic Shortcomings He Was Beginning To

Establish Himself As Something of a Leading Guitar Stylist

In The Rock-Blues Field, Though A Lot of The Rock Audience

Thought Alvin’s Playing Was A Watered Down Version of The

Real Thing Currently Being Exhibited By Eric Clapton,

Peter Green and Jeff Beck.

ARTISTIC DILEMMA:

Alvin Lee’s Popularity Had A Lot

To Do With His On Stage Antics. With Something of A Stud

Persona, Alvin Had All The Arrogance It Needed For Him To

Become A Guitar Hero, Vividly Contorting His Face While

Seeming To Produce His High Speed Runs Effortlessly.

Ten Years After’s Third Album

Called "Stonedhenge" (Note The Hip Crassness of The Title)

Saw The Group and Alvin Lee In

An Artistic Dilemma. As They’d Openly Admitted Their

Dissatisfaction With Their First Album, (Their Only Studio

Album At That Stage), Stating Candidly That Work In The

Recording Studio Came So Much Harder Than On Stage.

"Stonedhenge" Was A Dire Album,

With Alvin Keeping Himself Surprisingly Enough, A Very Low

Key Profile. What There Was of His Playing Was Restrained,

Only On "No Title" An Early Indication of Just How

Embarrassing Alvin’s Lyrics Could Be, Did His Guitar

Playing Come To The Fore. Again, It Was Short On Aesthetic

Value, But Rock Has Never Been Renowned For Its Good

Taste, and Alvin Lee’s Playing On The Cut, Was Heavily

Distorted and Very Fast, and That Impressed A Lot of

People.

Their Subsequent "Ssssh" Album

Saw Ten Years After and Alvin Lee Finding Their Recording

Studio Feet. This Time The Cover Art Showed Who Was Ten

Years After’s Main Man, As The Album Cover Was

Entirely of Faces By Alvin Lee. On "Ssssh" Alvin Blatantly

Copied Eric Clapton’s "Woman Tone" Technique, Thus

Producing A blurred Fuzzy Effect.

The Band Had Become A Lot

Heavier and So Had Alvin, Tightening Up His Playing Style

Considerably. His Adaptation of "Good Morning Little

School Girl" More Than Anything Else On The Record Shows

Alvin’s Adaptation of The Eric Clapton Mode of Playing,

Although It Lacked Eric’s Finesse. The Style Alvin First

Demonstrated On "Ssssh" Found Its Way Onto The Next Two

Ten Years After Albums, "Cricklewood Green" and "Watt" and

The Group Had By This Time Maintained Full Momentum

Spending Spending Much of Their Time On Vast Money –

Earning United States Tours. Ten Years After Were Going

From Strength To Strength, Even Making The British Singles

Chart With One of Alvin’s Better Songs, Called "Love Like

A Man".

By The 1970’s The Blues-Boom Had

Burnt Itself Out, and For The First Time Ten Years After

Had Very Little To Do With White Blues Rock, Concentrating

On Songs In Acoustic Settings. Alvin Himself Had Improved

As A Guitarist and For The First Time In His Career Showed

A Modicum of Taste In His Playing. A Track Called, "Hard

Monkeys" Shows Alvin’s Playing With More Ferocity Than

Ever Before and Managing To Couple This Added OOMPH With A

Slicker Tone. His Guitar Style Improved Further On Ten

Years After’s 1974 "Positive Vibrations" Album

Which It Was Rumoured At The Time, Could / Would Be The

Band’s Last Studio Album. As Alvin Lee By This Time Had

Established Himself In A Palatial Country Manor House.

Including A Recording Studio Located In One of The Many

Out Buildings On The Vast Property, and Called "Space

Studio" – Recorded Here Was Alvin’s First Solo Album, "On

The Road To Freedom" In 1973. With Mylon LeFevre, A

Musician With Strong Leanings Towards Country / Gospel

Music. The Album Also Included Material From George

Harrison and Ron Wood. ("Woody") Both of Whom Played On

The Album. The Title Track Again Portrays Alvin Lee As A

Very Fine Rock Guitarist, Slick, Sharp and Precise Without

A Trace of His Former Self-Indulgence.

Copyright: 1973 / 1974 / 1975 –

From Phoebus Publishing Company (PBC Publishing LTD).

169 Wardour Street, London

W1A2JX – Made And Printed In Great Britain By Petty and

Sons LTD. Leeds…And Ten Years After Elvis Came Alvin Lee,

The Demonic Wizard of Blues – Rock With A Lightning –

Swift Guitar Technique.

|

By – Steve Peacock

|

|

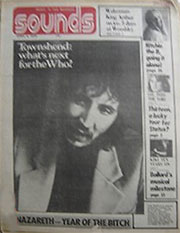

From Sounds – April 5, 1975

You’re looking at a free man who hopes to create

Nashville – on – Thames. He doesn’t know what the future

will bring, but he’d like a hit single.

Article:

Show me Alvin Lee and I’ll show you a man who has discovered

indecision as a positive way of life. He’s slipped the leash

on the band that made him rich and famous and he’s allowing

Plan B—Alvin Lee & Co.—to dismember itself with the minimum

of formality. “It was like the evolution of Ten Years After

over eight years taking place in three months”, he says.

Which is not to say that AL&C became hollow product—merely

that it ran as far in its chosen direction as Alvin Lee

wanted it to run with him on board. “This band really got

into jazz as a natural kind of leaning,” he says. That was

fine, he didn’t want to mould them any more than the main

songwriter, singer, front man, soloist and provider

inevitably shapes a band. But the way the band was

developing wasn’t the way Alvin Lee wanted to make music

further than the end of this month. “It’s great, but that

attitude of jazz seems to be “well, there’s an audience

there but don’t let it affect you too much.” If there’s an

audience there, I’m always very much aware of the fact. I

want to deliver something to them that’ll get ém off. That

doesn’t seem to be the attitude of jazz—jazz is

introvert,

and if this band were to continue it’d develop more towards

that and it isn’t really what I want to do.”

Quite what he does want to do is not so clear—not in

terms of style or specific musicians anyway. “There are

options: there’s country, there’s rock…I’ve got a strong

leaning towards getting back into R&B, getting back towards

the old stuff, perhaps leaning towards the blues a bit.

Chunky…chunky funky. I’m going to experiment. I’ve a strong

feeling that I could go any way from now. I’m getting off on

all the styles there are. Maybe the next album will be a

couple of tracks with this band, a couple of something else,

a couple…but I don’t know if it’s the right approach. That’s

the thing. It’d be fun, but…” The right approach can only be

what he fancies doing at the time –yes? “But it is nice to

be able to go out on the road with the same band that made

the album, so you don’t have to get people copying things

that other did on the album. “That’s what nearly happened

with this band but luckily they were strong enough to put

their own personally onto it, and anyway we only did half

the album on stage. But whatever happens next, it’ll grow

out of the next album I do—I now accept that changes take

place, and I’m now inviting them.

“I’ve got a strong leaning to get more into recording and

producing, but I know that after a few months I’d start

getting itchy feet again. I’ve been touring since I was 16

and you get something that builds up inside you that you’ve

got to release, and that you can’t release any other way.

And I’m addicted to America—I have to get out there at least

once a year just to get the buzz from that.”

Ah—the roar of the greasepaint and the smell of the Holiday

Inn. Alvin Lee may have the comforts of home and a

remarkably well equipped studio in his backyard, but you’ll

still find his butt shakin´ and his guitar wailing in

Knoxville, Tennessee—even Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire.

When he struck out on his own with the And Company project,

Alvin Lee was more or less starting again: it was hardly a

balls-on-the-rail venture, to the extent that he had money,

he could afford a good band and his TYA-made name guaranteed

him a certain amount of built in audience appeal. Yet it was

still quite a bold venture when you consider that he could

have spent the time in his studio or sun soaking in the

Bahamas or Hawaii, grinding out a swift TYA tour and album

each year to keep the accountant smiling.

With the original team of Boz, Tim Hinkley, Ian Wallace and

Mel Collins he had the makings of a rock band with enough

drive to satisfy his baser instincts, and enough funk to

make it a dramatic change from TYA: Boz split to Bad Company

before that could ever face the crowds, and the band that

played the Rainbow concert (from which the live album was

recorded) was rather hastily assembled. Neil Hubbard and

Alan Spencer and the Kokomo singers were recruited 10 days

before the gig, but returned to base before AL&C went on

tour.

With the touring band as it turned out—the basic

Lee/Collins/Wallace nucleus plus Steve Thomson and Ronnie

Leahy from Stone The Crows and percussionist Brother James—the

idea moved yet another stage away from its origins. It

worked and Lee enjoyed himself—the music and the situation.

“America was so different it was almost like going for the

first time. What was really good was coming off stage and

talking about music and listening to the tapes…having a bit

of a jam. It was a different relationship with the band, a

lot more like lads on the road—less professional but more

fun. There were a lot more downs as well as the ups—we’d

have incredible long dissections of things that went wrong,

have a sound check the next day and sort it out. With Ten

Years After we used to sleep in the afternoon, get a call at

six or seven, get to the gig at 8:30, tune up and play.” In

a way, the whole process had been a kind of exorcism for the

man who felt himself lumbered with the flying fingers image.

He was able to lie back as a musician and see the

possibilities, but perhaps he over reacted against his

history. “During the tour I managed to conquer the feeling

of wanting to do something loud and raucous but not doing it

on principle. I finally did it, got into some of those

tasteless things I was wanting to do, and the fact of not

doing from the beginning made it all the more effective. It

was really nice and gradual the way it should be.”

Having shown bell book and candle of laid back funk to the

heavy metallurgist that lurks within him, he feels confident

enough to let him out for a trot every now and then.

It was something he had to go through. But with the European

and American tours, he feels this band has run its course

and he is ready for something new. “If this band really

wanted to stay together and had a clear idea of what they

wanted to do, then I’d do it, but first I need to look

around a bit, get some new inspiration and write some new

songs.” In any case it seems unlikely this band will survive

as it is (Mel Collins is pretty certain to rejoin Kokomo),

though it seems equally likely that Ian Wallace will stay

close to Alvin Lee: “He’s got to be the best drummer in

Britain”.

While in America he managed time off to do some sessions:

one in Los Angeles for Bo Diddley, and several nights in

Nashville on sessions for the 25th anniversary album for

Earl Scruggs, alongside people like Charlie Daniels, Willie

Hall, Don Nix—the crew. Among his plans is to: ship Charlie

Daniels band over to his studio this year for a

Nashville-On-Thames sessions.

He’s also going to be working on a film—a kind of “up to

date Fantasia based on the idea of Atlantis”—for which he

will provide the music and be involved with mapping our

sequences. That’s in its infancy at the moment.

And there’s another thing: “I must admit I’ve been toying

with the idea of taking the easy short cut with the old hit

single. I know I’ve been against it all my life, but the

Average White Band have proved it can be done with something

that’s just good music. I’ve thought about playing around

with different styles of things, seeing if any of them pick

up.” That should lay the TYA great coat ghosts for good.

Meanwhile, it’s a case of finishing the current tour,

getting out and listening to some music, writing some songs,

and getting some musicians together to play. “I’m going to

get on playing music and see where that takes me.”

|

|

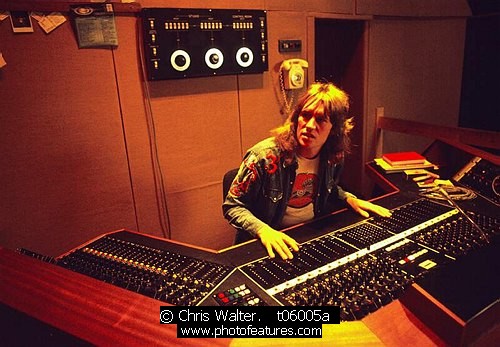

May 17, 1975

Antenne 2 (today

France 2, French National TV)

TV show Juke-Box

presented by Freddy Hausser

They visit Alvin Lee in

his studio. The 40 minute program

includes an interview, Alvin

playing acoustic guitar, singing

parts of new songs

as well as Time

And Space, playing guitar along Ride My Train

They show footage from the

Rainbow concert,

playing an alternative version

of Going Through The Door

a track from the group FBI,

also Alvin jamming with FBI

|

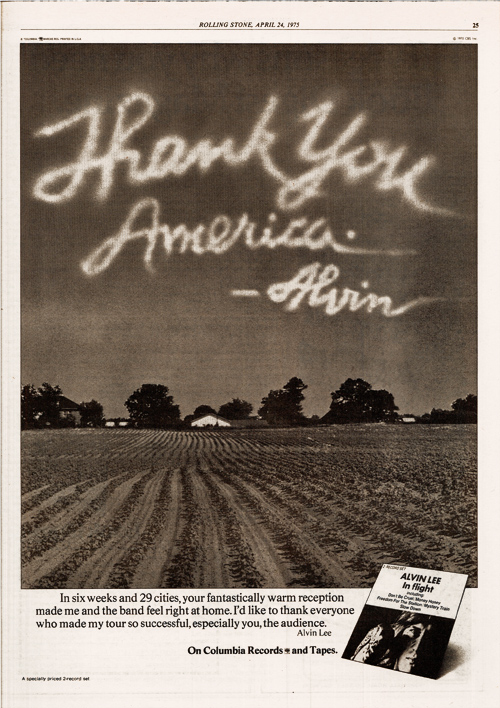

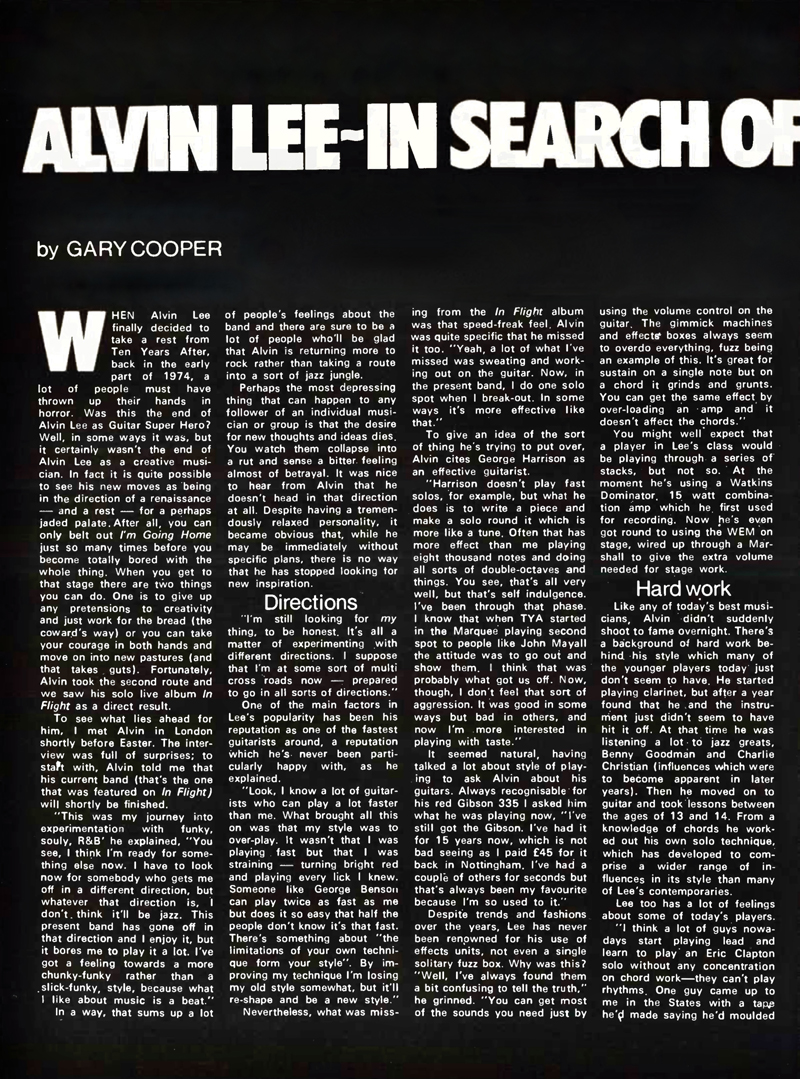

May 1975 - BEAT INSTRUMENTAL Magazine,

England

page 12

page 13

|

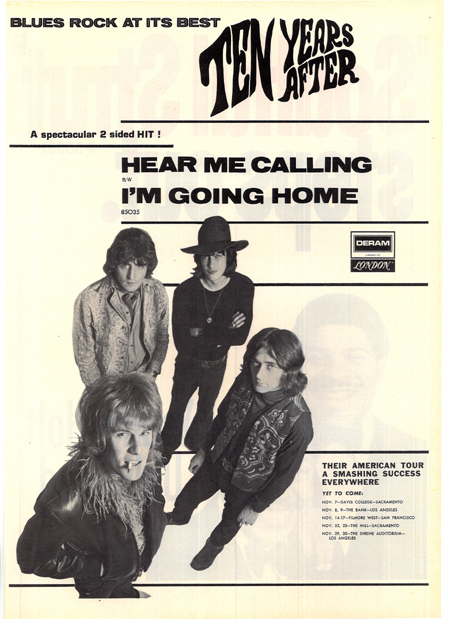

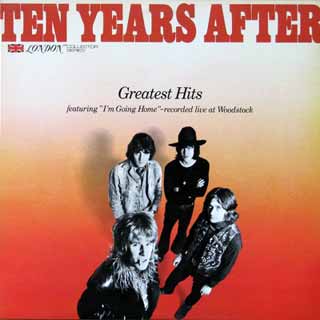

24 May 1975, Melody

Maker

Ten

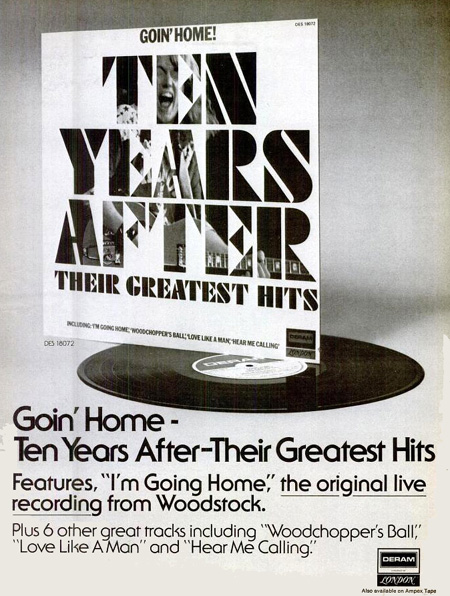

Years After - “Goin’ Home!” (Chrysalis)

A

compilation album of the first three years of Ten Years

After’s existence. And a pretty neat selection of

some of their best-known numbers, including, as the title

suggests, the TYA classic “I’m Going Home”

a

live version from the Woodstock film.

Alvin

Lee has taken a bashing from some critics over his

“speed-trip playing,” but he and TYA were undoubtedly

worthy

of the success that came their way in the late sixties and

early seventies. Lee became one of the

legendary

guitar heroes and I always thought his playing could be

tasteful at times as well as brash and violent

as it is usually regarded. In

judging Lee the critics often missed the point.

The

band were exciting to watch and it was this excitement,

through flash playing that Lee tried to convey on record, especially on the “Undead”

album, which was

recorded live, and “Ssssh.”

On

this album we have: “Hear Me Calling,” “Going To Try,”

“Love Like A Man,” “No Title,” “I Woke Up This

Morning,”

“Woodchoppers

Ball,” and “ I’m Going Home.”

“Love

Like A Man” is the studio version and it is debatable

whether the live number should have been included,

although

the studio one is much more polished and precise.

“I

Woke Up This Morning” is an object lesson in what can be

achieved without straying far from the basic

blues theme. Lee’s

playing is beautiful, with the rest of the band filling

out the bottom. “Going Home,”

the closer, sums up

the

essential TYA in a nutshell. You can almost see Lee

onstage snarling out the vocals and ripping into

his axe, no quarter asked or given with the excitement rising

as the audience lets its hair down.

But

one of my favourites is “Hear Me Calling,” with Leo

Lyons’ bass thudding out the riff and Lee soloing in a

restrained fashion. An

excellent album showcasing all that Ten Years After had to

offer---and that was a hell of a lot.

By E.M.

This album represents the first three years in the life of

Ten Years After from their beginning playing small British

clubs, to the peak of their world wide acclaim at the

legendary Woodstock Festival, and with it's distinguished

fragment of rock history.

|

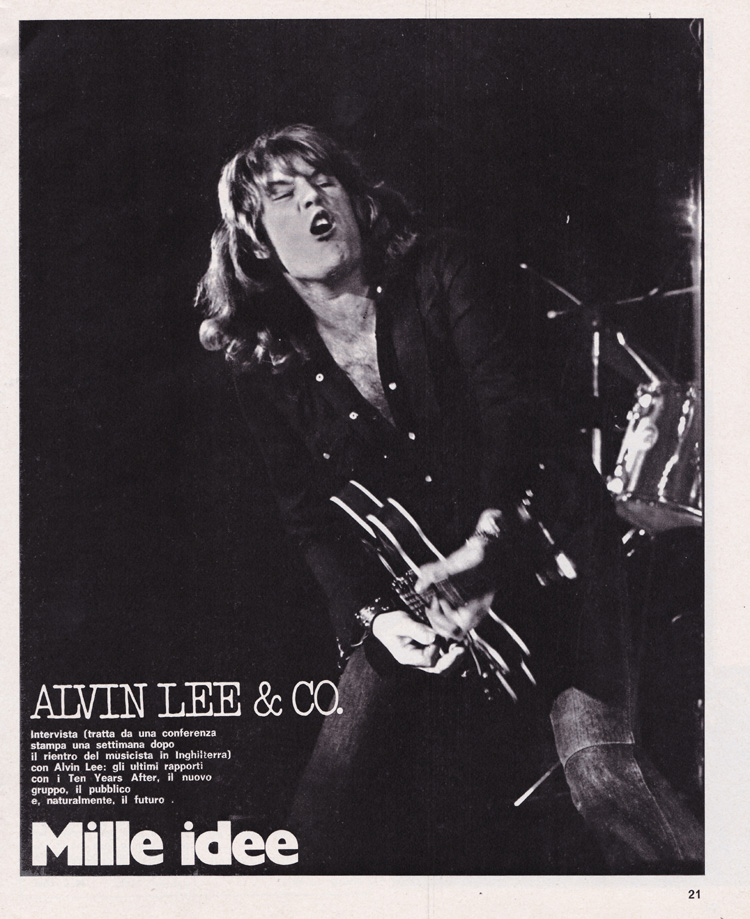

25 May 1975

- CIAO2001, No. 20

|

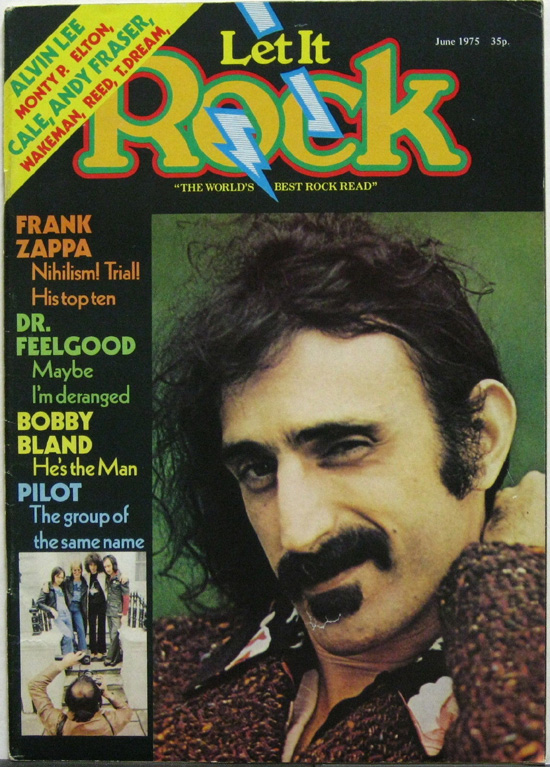

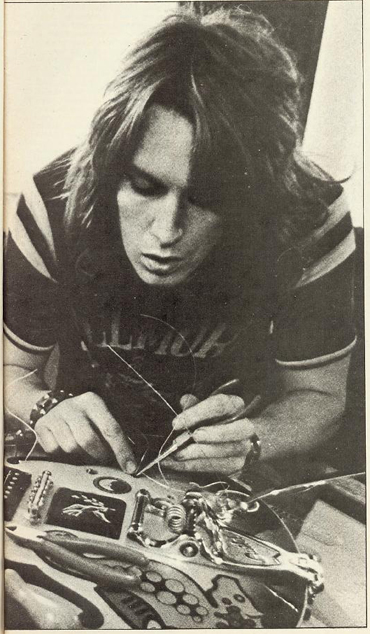

June 1975 - Let It Rock Magazine

The world's fastest guitarist takes up his generator,

JBL's and bits in between...

and chooses ten discs to keep

him company

"My Top Ten" from Alvin

Lee:

- “Baby Let’s

Play House” – Elvis Presley: Because there’s a great bit

with Bill Black playing bass that goes…docka-docka-docka-docka.

- “Sweet Little

Rock and Roller” – Chuck Berry. This is possibly my

favourite of his songs. There are a few others I would

include, but I would want to listen to them all again

first.

- "Brother Jack

McDuff with George Benson". It’s done in a roadside club.

It’s really live, sweat dripping down the walls, kind of

feeling; glasses chinking in the background. They blow a

storm…Good musicians atmosphere. He’s probably playing

his best. Put him on stage at the Albert Hall and he

will play well, but won’t have that down to earth

funkiness / looseness.

- "Abbey Road" –

The Beatles: The melodic-ness of it. The fact that their

personal relationships were not visible. Paul has

amazing melodic sense – he’s not a rocker or a raver, or

a heavy musician, and he plays a very tuneful bass. For

the same reason, I would also say.

- “Maybe I’m

Amazed”: Paul McCartney. To me, this is what the Beatles

were striving for.

- "Burnin´ The

Wailers": They are the best. The complexity and the

neatness of it. The experiments – they are almost

virtuosos. There is a lot of good basic reggae, which is

just as good in feel, but the Wailers put something

extra in – harmonies and things.

- "Music From A

Doll’s House": (Band) Family. The music is very good,

obviously. The recording is five years ahead of its

time. The quality of it and the effects.

- "Dark Side of

the Moon": Pink Floyd. I like the mood. When I listen to

Pink Floyd I don’t listen to how he (David Gilmour) is

playing the guitar, or the technique of the drums, I

just go for the mood. Being a musician, professionally

you tend to listen to a lot of music critically and

analytically, and you don’t enjoy it that way. I can

listen to the “Floyd” or some electronic music and hear

it, just like an average man on the street.

- “If 6 was 9": Jimi Hendrix. The whole album, actually, but this song

in particular. Excellent stereo effects, phasing and the

like. Hendrix’s influences didn’t come from any obvious

sources, he was very much his own force. He was not a

great guitarist, in the classic sense, but what he put

over was feel and his personality.

- "Kodachrome”

– Paul Simon: A very precise, very professional album.

He makes almost seem-less recordings, with everything

crystal clear. You seldom find a phrase in there that

isn’t one hundred percent effective.

|

|

Creem Magazine 1975

I admit it. The first line of this article was

written a week before the concert: “Having assured

us all most emphatically at Woodstock that he was `Goin´

Home,´ old butter fingers is back…”

Well, it was a waste of time and talent. The fact is

that Alvin Lee has just broken a precedent: not only

is he back, but he’s also better than ever. Claws

in. Next victim, please.

So Alvin’s back. Who isn’t? But it’s news this time.

He’s doing what Eric Clapton wanted to do:

sacrificing lone star status to be one of the boys.

The difference is that Alvin Lee has a strong and

spirited bunch of musicians to play with.They don’t

kowtow, and he has found strength in the challenge.

He has to work for his riffs, and he burns brighter

with every exchange.. |

"I kept telling everybody

I wanted to do

something else!".

|

The final few moments of every

song are explosive, but never fear, Alvin is in

control now. It’s no longer how many notes he can

play that counts; he’s out to prove how well he can

play them. Quality over quantity at last. Of course he has a lot of help to keep him in check.

Alvin Lee and Company is no small time operation. There are

the two members who have been with him for over a year, the

amazing Mel Collins on various horns, and the dynamic Ian

Wallace on drums. Newer members include Ronnie Leahy who

handles the keyboards, and Steve Thompson on bass. Brother

James is a killer on congas and other percussion instruments,

and Donnie Perki and Juanita Franklin make up the angel’s

choir. |

| That’s a lot of band to handle. Alvin Lee tackles being back

with a vengeance. He does have a mean streak-the meanest

mother in rock and roll, attitude wise. From the moment he

told promoter Howard Stein where he could stick his

spotlights, there was no real doubt that Alvin Lee could

chuck it all, any time. “I’ve done that a few times,” he

says. “I mean I did it after Woodstock. I hid away for about

six months. And everybody said I was mad because the band

could have been out makin´a fortune on the strength of

Woodstock. That big screaming rock and roll circus thing

I’ve always been against.

He may have been against it, but his business associates

and various money men were not. He was subsequently held in

check, which led to his retreat, which led, ultimately, to

his rebellion.

“I kept telling everybody I wanted to do something else! And

nobody would take me seriously, until I said, well, “Here

I’m gonna do it! HERE I COME!! And I’m having to prove the

fact that I’m serious.”

The music ranges now from the mellowest of jazz and

soul-a Junior Walkerish “Freedom For The Stallion,” no

less-to the bluesiest of blues. Alvin’s guitar is at times

supportive, although always with a sting. When he has the

show to himself, he really lets himself go. Letting go now,

however means controlled combustion, there’s more feeling

than flash. Whatever he does is usually right for the moment. For

instance, “Every Blues You’ve Ever Heard” was

and wasn’t. Though it did utilize every blues cliché

imaginable-what blues doesn’t-he couldn’t have made them

seem as urgent or as authentic years ago. That is the

difference-maturity. The precocity has given way to a kind

of raunchy practicality.