|

GOLDMINE MAGAZINE From September 28, 1984

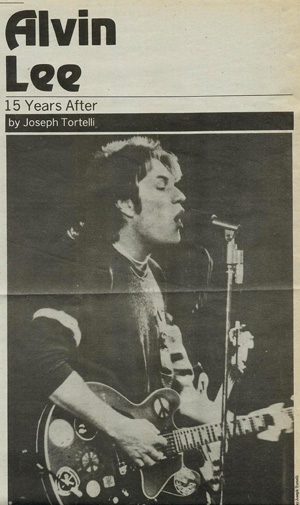

ALVIN LEE - FIFTEEN YEARS LATER Written by Joseph Tortelli

He electrified Woodstock with his fiery guitar playing. His

flash and speed elevated him to the status of pop icon. The

music scribes dubbed him "The Fastest Guitar in the

West." Alvin Lee's prominence in the rock `n´ roll world

has declined markedly since those tumultuous days. Today his

tour bus arrives at clubs , not festivals or arenas. His

audience is older in age and smaller in number than it once

was. But memories of the guitarist's stunning performances

with  Ten Years After continues to attract the faithful.

Relaxing in his plush tour bus after a torrid show at Boston's

Channel Club, the veteran rocker looks remarkably fit and

youthful. He recalls his introduction to music. "I

started playing clarinet," Lee points out. "I played

clarinet for about six months. I used to listen to Benny

Goodman. And listening to him I got to hear Charlie Christen,

who was a very good guitar player." The guitarist from

Goodman's band had a significant effect on the neophyte

musician. Lee remembers, "I went down to the pawn shop

and swapped my clarinet for a guitar, much to my parents

horror." Lee's initiation to the secrets of the guitar

came through jazz, not rock `n´ roll. Django Reinhardt,

Barney Kassell, and George Christian were among his earliest

influences. But the young Lee found himself intrigued by

another sound too. He credits his father with introducing him

to blues. "My father is a blues fanatic," Lee says.

"He used to collect chain gang songs, prison work songs,

and things like that. I had a great repertoire of blues songs,

thanks to my old man." Ten Years After continues to attract the faithful.

Relaxing in his plush tour bus after a torrid show at Boston's

Channel Club, the veteran rocker looks remarkably fit and

youthful. He recalls his introduction to music. "I

started playing clarinet," Lee points out. "I played

clarinet for about six months. I used to listen to Benny

Goodman. And listening to him I got to hear Charlie Christen,

who was a very good guitar player." The guitarist from

Goodman's band had a significant effect on the neophyte

musician. Lee remembers, "I went down to the pawn shop

and swapped my clarinet for a guitar, much to my parents

horror." Lee's initiation to the secrets of the guitar

came through jazz, not rock `n´ roll. Django Reinhardt,

Barney Kassell, and George Christian were among his earliest

influences. But the young Lee found himself intrigued by

another sound too. He credits his father with introducing him

to blues. "My father is a blues fanatic," Lee says.

"He used to collect chain gang songs, prison work songs,

and things like that. I had a great repertoire of blues songs,

thanks to my old man."

In 1955, about a year after he picked up the guitar, Lee

remembers rock `n´ roll hitting England. He mentions Scotty

Moore, Chuck Berry, and Lonnie Mack as a few of his favourite

50's guitarist. But, he adds, " I had a pretty wide range

of influences - John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters. I used to like

Chet Atkins, too." American rock `n´ roll records were

not always readily available to British kids during the 50's.

Lee developed a unique method of landing the newest releases.

"I used to buy all the American records," he

enthuses. "I have an aunt in Canada who used to send me

all the latest American records. It was a big deal in those

days to get a Chuck Berry album six months before anyone else

had heard of it."

Though he studied with a guitar teacher for about a year,

Lee is essentially a self-taught musician. "I avoided

taking lesions and reading music, because it will affect your

style," he says. "I never used to copy anybody else.

Maybe I'd copy a style. I'd hear a Chuck Berry record and I'd

play a solo the same style as him. I wouldn't copy it note for

note. In that way you can give it your own stamp. I've never

been a good copier, probably because I can't. If I listen to a

good solo, I can't work out the notes then play. I'd rather

choose my own and just play it with a similar feel." Lee

attributes his speedy guitar technique to encouragement from

appreciative audiences. "I think it comes from the

adrenalin I get off playing live," he says "When I

get a good audience, I get them off and they get me off too.

Sometimes I hear a tape after I've played and say, "Good

Lord, is that me?" because I don't know I'm doing it

myself. It's just the adrenalin the audience kicks out of you."

The youthful guitarist knew that he was destined to become

a professional musician. "I left school when I was

sixteen," he says. "I went straight into it, never

had a proper job." Like most teenagers in a similar

situation, Lee played clubs near his family home in

Nottingham, England. He recollects that he joined a half dozen

local bands, the first of which as named the Jailbreakers.

Lee's guitar style, rooted firmly in blues, hindered his

career in initially. "It wasn't accepted," he

explains. "I used to get banned from places because

people couldn't dance to the music I played. But I played it

anyway." The British blues boom of the early 60's changed

things. Local fans recognized Lee as one of the top musicians

on the Nottingham circuit. Though he recorded a few demos

during this period, none made it to vinyl.

Two other Nottingham lads, bassist Leo Lyons and

keyboardist Chick Churchill, also gigged in area clubs. They

asked Lee to join their band, the Atomites. Lee laughs,

"I said, "Well, yes, but only if you change the

name." Lee dates the beginning of Ten Years After to

1965. Originally, they were called Bluesyard. But, Lee says,

"We decided that was a bit too bluesy, so we chose Ten

Years After." Ric Lee, a drummer from Mansfield - which

is a town about fifteen miles from Nottingham - completed the

line up. All outstanding individual musicians, Lee refers to

early Ten Years After as "The Cream of the Nottingham

area." Even in their earliest days, Ten Years After

displayed considerable musical versatility. They played rhythm

`n´ blues, country, jazz and rock `n´ roll in addition to

their mainstay, blues. Oddly, the British beat which dominated

the mid 60's did not excite the members of Ten Years After.

Alvin Lee appreciates the irony. "I've always liked

American music," he concludes. "It's funny that

Americans like English music and the British people love

America music."

Ten Years After became a staple on the club circuit in and

around Nottingham. They gained a national reputation with a

series of dates at London's Marquee Club. Yet record companies

had their reservations about the commercial possibilities of

bluesy instrumentalists. With the success of Cream in 1966,

the record labels decided that electric blues was a saleable

commodity. Ten Years After signed with Deram Records. Their

first album, "Ten Years After" was issued in 1967.

Lee is proud that their recording contract allowed band

members to showcase their musicianship and style. For an act

like Ten Years After, an entire album, not simply a pop

single, was essential. "We were one of the first bands to

get an album deal ," he boasts. "Before then, you

did a single and if your single sold, then you could record an

album. We got offers to make an album."

The rock world, tiring of the mid - 60's pop sounds,

welcomed something different. On both sides of the Atlantic,

the burgeoning progressive movement found Ten Years After a

robust alternative to top forty bubble-gum. The bands late

60's albums gained airplay on America's FM radio stations

along-side Cream, Jimi Hendrix, Jethro Tull and a host of

others. A number of club tours widened Ten Years After's

trans-Atlantic appeal. According to many critics and blues

enthusiasts, this was the period of the group's greatest

creative achievements. Apparently Lee agrees. Undead, a live

album recorded at a British club date, remains his favourite

Ten Years After release. "I enjoyed that," he says,

"because I thought it captured what the band did

best." He also includes Ssshh and Cricklewood Green as

equally enduring recordings.

Ten Years After's Tours and albums secured the band a solid

place with underground rock fans. In the summer of 1969, the

group was given an opportunity to expand that base

dramatically. A performance before half a million rock fans at

the Woodstock festival in New York State was the turning

pointing the band's career. Lee carefully notes that the

Woodstock appearance, itself, did not cause a great stir.

"When we did the actual festival, it was a great

experience. But we carried on for about a year playing the

same kind of venues for about 6 or 7,000 people." The

Woodstock film and album soundtrack were released in 1970. Ten

Years After filled eleven minutes of time with the steaming

rock `n´ roll exercise called, "I'm Going Home."

The vinyl and celluloid catapulted the band to the top of the

rock `n´ roll world. And Lee, whose guitar playing and

singing were prominently featured, emerged as a star.

"The movie came out and that made a lot of difference," according to Lee. "Suddenly we were

playing giant auditoriums in front of 30,000 people." But

the acclaim exacted its price. The hassles and pressures of

touring grew with the audiences. Alvin Lee emphasizes the

connection. "Although that's when the band got really

popular, that was the start of the band breaking up, because

the gigs got less enjoyable then… When you play in those big

auditoriums, you can hardly see the audience. You've got

security guards and cops and echo and everything else. You

play five or six nights a week in those places and it starts

to get a bit more like work than playing. I think the whole

band got disenchanted playing those giant places. Nobody

wanted to tour after a while."

Though the seeds of disillusionment had been planted, the

groups dissolution was not at hand. More triumphs awaited. In

1970, their contract with Deram expired after six albums. Many

labels expressed interest, but Ten Years After was signed by

America's leading record company, Columbia. "I think

Columbia picked us because we were doing really well

then," Lee suggest. "Clive Davis came to Madison

Square Garden, and he saw 20,000 people screaming and yelling

for us. He'd be pretty stupid not to sign us."

The Columbia contract resulted in the group's first gold

album, "A Space In Time." From the fall of 1971, the

LP included Ten Years After's only top 40 single, "I'd

Love To Change the World." A Space In Time seemed to

indicate a significant new phase of artistic growth for a band

attempting to move beyond its blues rock roots. "It's

probably my favourite album as far as the songs go,"

declares Lee. "I had about a year off to write those

songs, which helps. You can't write a good song in three

minutes."

But the commercial success did little to alleviate the band

members personal dissatisfaction, "If touring isn't

fun," the guitarist says, "no amount of money can

make it worthwhile. You've got to have fun playing. If you did

it for the money, you'd go crazy. If you don't enjoy it, no

amount of money in the world would be worth it." Rumours

abounded that Lee's superstar status caused tension within the

Ten Years After entourage. It was the age of the guitar hero.

And Alvin Lee took his place besides his countrymen : Eric

Clapton, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck. "It was a bit

embarrassing in those days," Lee says. "People

saying that I was "the fastest guitarist in the

West." And I know that I wasn't. It was complimentary .

Looking back on it, I was just a bit confused. I wasn't too

sure about putting myself around like that . I was probably a

little more modest than people made me out to be. But,"

he adds with a smile, "how can you be a modest, flashy

rock `n´ roll guitar player?"

Through the years Ten Years After persisted, Lee pursued

outside projects. "On the Road to Freedom". A duet

with American vocalist Mylon LeFevre , was issued in December

1973. The record featured an array of British superstar

sidemen, including George Harrison, Ron Wood, Steve Winwood

and Mick Fleetwood. "That was a little idealistic side

trip," says Lee of the album. "I met Mylon in

Atlanta. We wrote a couple of songs together in a hotel room.

And we had this long talk about making an album together. He

had a band called Holy Smoke. I got them on the Ten Years

After tour as the opening act. We wrote some more songs

together, When I finished building a studio in England, he

came over and we cut the record. It was all very homegrown and

idealistic. It's still one of my favourites. Nice music."

As for the supporting musicians, Lee says, "We had an

all-star cast on that one. That was Mylon. He was a good

hustler."

The scorching guitarist appeared to be heading in a more

mellow direction on his own. He enjoyed listening to

songwriters like Paul Simon, Jackson Browne and Lowell George.

The blues rocker even aspired to be counted among them. Lee

acknowledges that this was not a rewarding musical endeavour.

"I enjoy the music, but I wouldn't want to play like

that. I did once," he admits. "But then I realized,

"who needs two Paul Simons?" I'd only be a second

rate Paul Simon if I worked hard at it. So I do what I do

best, which is rock `n´ roll and blues."

The guitar player's separation from Ten Years After, at

first tentative, became definite and permanent in 1975.

"When Ten Years After didn't work anymore, I took about

six months off and sat at home and just really went

crazy," he says. "I realized that I had to keep

touring no matter what. I tried a few different things. I even

had a seven piece band. For awhile, I refused to play any of

the old Ten Years After songs. That was all part of living and

learning. "Then on time I stopped by to see Jerry Lee

Lewis. He didn't do "Whole Lotta Shakin." He did all

country songs. I was really disappointed. Coming out of the

club, I realized that when people came to see me and I didn't

play "I'm Going Home" or "Little School

Girl," they'd feel the same way.

"I grew out of wanting to be a musician's musician and

playing for myself," Lee continues. "You can sit at

home and play for yourself all you like. If you're going to

play onstage, the idea is to get people off and give them a

good time. I realized that I wanted to give them what they

wanted to hear - within reason. So I play 60 to 70 percent of

the good old songs now."

Alvin Lee's October 6, 1983, set at the Channel proved his

point. Accompanied by former Crosby, Stills, and Nash bassist

Fuzzy Samuels and drummer Tom Compton, Lee ripped through

"Good Morning, Little Schoolgirl," "Choo Choo

Mama," "I'm Going Home," and other Ten Years

After memories. He also slipped in the rock chestnuts,

"Sweet Little Sixteen," "Slow Down;" and

"Hey Joe." A pounding drum solo and a surprisingly

entertaining bass solo by the dreadlocked Samuels supplemented

the expected guitar fireworks. It was the kind of performance

which had fans - perhaps imagining it was 1969 again -

screaming for more. The veteran guitarist expresses enthusiasm

about such club appearances. "I like doing these clubs

like we did tonight," he offers. "To me, that's the

ideal gig, because the audience is right there and you can

feel them. And the sound is tight."

Though Lee's career sputtered during the late 70's and

early 80's he is prepared to continue working. "I got

disenchanted with recording because of the record companies

wanting commercial singles which has never been my bag. To be

honest, I didn't even like the last couple of albums I

did," he confesses. "I did them too rushed. So I've

decided to take my time. I've been writing for about a year

and a half. The next album is going to be a good one if it

takes another year. At least I'm going to like it when it

comes out. With a little luck I might have something out by

summer. But no promises, it's got to be good."

Lee still plays with his Ten Years After mates

occasionally, through a permanent reunion is unlikely.

"We just did the Marquee Club, where we first started

playing in London. The club had its 25th anniversary, and we

got together for a couple of nights there. Then we did the

Reading Festival," Lee adds. "But we decided just to

do the odd festival here and there for a bit of fun. The other

boys are still settled down and married. I'm just a rock `n´

roll gypsy. I love touring. Those guys like a little order in

their lives."

The singer / guitarist expects to be on the scene for some

time to come. "If I'm alive," Lee declares,

"I'll be out there. Don't worry about that."

|