|

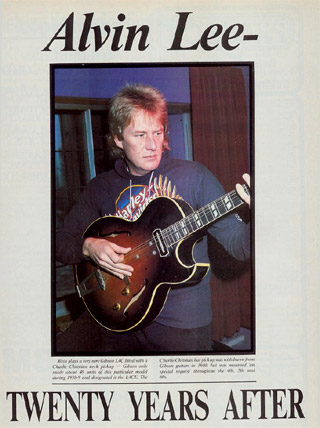

Alvin Lee – Twenty Years After The likes of Eddie

Van Halen and Yngwie Malmsteen were still running

around in nappies when Alvin Lee was the fastest

guitar in the West. With his band – Ten Years After

– Alvin captured the hopes of many aspiring string

benders, and still continues to do so in the

eighties, but he now performs under just his own

name. His latest album, “Detroit Diesel”, is just

about to be released in the UK having proved a big

success in the USA. Bob Hewitt chatted with Alvin

about his career and the new album.

The new album is my first one for about five

years. I’ve had a long lay-off, because I found

myself putting out records I didn’t like very much,

mainly because of pressure from record companies to

push another album out although I didn’t really have

the songs! The previous album was called “Freefall”:

it took about six months to come out, and then I

found myself touring around the world. I would do a

radio station and people would say, “tell me about

the new album…” and I would say “Well, I like one of

the tracks on it…” So I thought it had to stop; if I

was putting out albums I didn’t like, how could I

expect anyone else to like them? Basically, I’ve

spent the time here in my own studio finding out new

techniques and stuff like that. I’ve been doing gigs

as well, plenty of them in Europe and the USA, but

none in England. I’ve got a three piece working

band, which sometimes goes to a four piece when the

budget permits! I perform under my own name—not Ten

Years After—and I have Alan Young on drums and Steve

Gould on bass. Micky Feát played bass on the album,

and he is in the occasional four piece outfit,

because Steve can also play guitar, keyboards and

sing…clever bloke! Basically, I’ve just carried on

earning my living as a musician—that’s all I’ve ever

wanted to do. I’ve always avoided the “Rock Star”

kind of image and have never gone in for gold lame´

suits and things like that! To be honest, I think

it’s quite a privilege to be a working musician, and

to make a living out of it. That’s what my heroes

have done, like Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker,

they’ve played ´till they’re 90 or so. Really,

that’s all I’ve ever wanted to do, I’m not into

getting hit records and retiring at an early age—I’ve

tried retiring…it’s boring.

Tell us a little

about the new album “Detroit Diesel”.

Well I think it took me a long time to find out

which direction I wanted to go in, having had five

years off. I’d heard all the new Eddie Van Halens

and things, so I thought ´How am I going to

represent myself?´ So I got back to the basic roots,

things I like, straight ahead rock ´n´ roll blues—I

figured I should do what I do best. For people who

don’t know what I do, it’s like re-introducing my

own style, and it’s probably nearer the old Ten

Years After format as far as energy goes, and I like

the songs. There is a tendency these days for record

companies to want pop songs and hit songs, they are

always looking for singles. I’ve always been an

album artiste really, and it takes a long time to

get a good song and then play it the way you want to

play it, and not lose out. Sometimes it can sound

commercial and lose some of its ethnic feel and

sometimes its ethnic and not very commercial! Now I

think I’ve brought the two together. I’ve used

computer drums and triggered synthesisers and

samplers, those kind of gadgets—really it’s old rock

with a new slant!

Most of the work

had been done here in your own studio, hadn’t it?

Yes, they are all original demo’s. I kept the same

piece of tape and changed bits here and there,

overdubbed and built it up. It actually sounds like

a live band, but it’s quite high tech. Who is on the

album with you? There’s a drummer called Bryson

Graham, Steve, Alan and Micky from my current band.

Tim Hinkley plays some keyboards, and a guy called

David Hubbard who is first class with synths. Jon

Lord plays Hammond Organ and George Harrison plays

slide guitar on a track called ´Talk Don’t Bother

Me´.

Leo Lyons from the old Ten Years After band plays

bass on the title track, ´Detroit Diesel´, and we’ve

got Joe Brown playing fiddle on another track with

his wife Vicky on backing vocals! Boz Burrell plays

bass on one track, in fact, we used to have a band

called The Gits about the time Ten Years After was

folding up which Boz and myself, Mel Collins on sax

and Ian Wallace on drums. That evolved into the

In-Flight Band which did the Live at the Rainbow

Concert, but it went a little bit too funky and

tasty for its time.

The techniques

used in making your latest album must be a far cry

from the old days, when you first recorded with Ten

Years After?

I’ll say! The first two albums

from Ten Years After were recorded live in the

studio. It was only four track in those days, but

even then I had started to get interested in studio

work. After the second album, ´Undead´, we basically

had our set `down´ so we started experimenting and

trying overdubs—all very exciting stuff in those

days. Now of course, it’s a more complicated version

of that. I still like the straight ahead technique,

because I sometimes think today’s technology is just

designed to make things take longer, and help the

studios make more money! There’s no doubt about it,

if you’ve got the songs and you rehearse enough, you

should be able to put the album down in a few days.

We always used to—those first Ten Years After

albums,

two days and that was it! …but nowadays bands go to

exotic locations in the West Indies, and it takes 6

months or longer! Oh yeah! Keyboard overdubs this

year, guitars next year…Scotty Moore is one of my

real heroes, and he did some great solos on the

Elvis records but he doesn’t like all this

overdubbing thing at all. He always went straight

onto the master tape. I remember him saying to me `I

don’t like those modern recording techniques—what I

like to hear goes down, if it ain’t goin´ down, I

don’t know what I’m doin´…´. If you’re really in

control in the studio, then you can use the latest

technology to the best results—whether it’s done in

five minutes or whatever. I remember somebody asking

if I wanted to play on a Bo Diddley album, and I

thought `great!´. I went along to the studio and

there was just an engineer who played the track and

I played my solo. Later some friends said `What was

it like to meet Bo Diddley then?´, but I never met

him: I’d played on the album but never saw a soul!

But I suppose that happens a lot now, you get bands

recording who have never actually met each other!

What about a tour to promote `Detroit Diesel´?

It’s nearly

sorted. I’ve got a few more three piece

gigs in Austria and Yugoslavia, then I think it will

be the four piece to play the stuff from the album.

I want to do gigs in this country, but I’m so out of

touch here I don’t know where to start to be

honest!

England tends to like fads and haircuts rather than

music, and I’ve found that the music press are

pretty trite and don’t really help anyone. I

remember when Ten Years After first came out and we

were doing the Marquee, people said `You’ve got to

hear this great band!´ As soon as we had success,

the same papers turned dead against us: they wrote

about´ a bunch of big headed gits who play in

America all the time´. They seem to enjoy putting

you on a pedestal and then knocking you off! It’s a

shame really, because I don’t think it reflects the

audience’s view at all. It’s the view of a narrow

minded minority—there’s always a strange faction

here in England. I remember during the blues

boom—because I was playing at that time—there were

blues `purists´. If you did an Elmore James song and

changed a note of the solo, they used to come up to

you afterwards and tell you, you hadn’t played it

`properly´. I used to really revolt against that,

because you can play what you like as long as it

sounded like a blues number. It’s funny you know,

they all used to wear long leather jackets and stand

around the front of the stage making notes! My

musical style seems to have gone right around the

houses, because I started out playing jazz and blues, then went into rock, then deeper into jazz

and funk. I went off all the Ten Years After

numbers—I even refused to play Goin´ Home for about

a year! I’ve come back to it all now. I think it’s

just a phase you go through, because a lot of

artistes turn against the numbers they are famous

for. I remember Hendrix used to dislike Hey Joe

which used to baffle me, because I thought it was a

great song, in fact, I do it in my set now and it

goes down a bomb!

What happened to Ten Years After—was it just the

natural demise of a band?

Well we were together for

nearly eight years, which is a pretty good run!

After about eleven albums I think we realised we had

gone as far as we could. In fact, we overworked in

those early years, because every band starting off

wants to fill the date sheets—and we worked for six

years solid: it was six months in the States, back

here for a day off, over to Germany for two months,

another day off, then Italy and so on… Suddenly

you’re due in the studio for an album, so you

think, `Better write some songs then!´. We used to write

songs in the taxi on the way to the recording

session! I think another reason for wrapping it up,

was to settle down with our families.

So the last time you all played together was the

Marquee Anniversary?

Yes that’s right, followed by

the Reading Festival. It was great and I actually

thought somebody would say it was good to see Ten

Years After together again and suggest we do it

again, but nobody seemed to notice, so I let it go.

You had quite a bit of chart success with your

early singles…..

Yes, we were in the top five with

`Love Like A Man´ and `Love To Change The World´ was

pretty big as well. But that was almost a sideline,

because they weren’t the strong numbers in the set.

We had Goin´Home and Good Mornin´ Little

Schoolgirl,

they were the show stoppers at a live performance,

but the singles were pulled off the album by the

record company.

Talking about the early days, how did your

musical career start?

Well, my father used to

collect very ethnic blues records, like chain gang

and work songs, so that was an early influence. Dad

also played a bit on guitar, with my mother and

sister, they had a country and western singing

band—very small time, local church hall jobs! There

was always a guitar lying around—we were a very

musical family—but at the age of twelve I started

playing the clarinet, although I’m never really sure

why, because I didn’t like the thing! With the

clarinet I started listening to Benny Goodman music,

but I found I was hearing more from Charlie

Christian than I was from Benny Goodman. To my

parents´ horror, I swapped the clarinet for a guitar

and spent a year learning jazz chords—vamping chords

and listening to Barney Kessell and Django Reinhardt

. Then the rock `n´ roll explosion hit England from

America, and I think Chuck Berry was the one for

me—in a way it was all the blues I was used to,

melted into rock `n ´roll, so I could understand it.

I started playing lead guitar and I didn’t think the

jazz chords were much use at all but in fact they

came in very useful later on. I never used to copy

things note for note, but just get the basic feel,

doing it my way, and I think that’s how my style

developed. I was Nottingham born and bred and used

to play in bands around that area—in fact, I played

with my first band, Alan Upton and the Jailbreakers,

when I was thirteen years old at the Sandiacre

Palace Cinema! Then there was Vince Marshall and the

Squarecaps. I used to play lead guitar with that,

and I would watch `Oh Boy´ on the TV and see Joe

Brown and Eddie Cochran. That was the first time I’d

ever seen a Bigsby tremolo arm, so I went down to

Dad’s shed to make one! I got this metal thing and

stuck it on my guitar, went to the gig that night at

the church hall. We were doing `Milk Cow Blues´. It

got around to my big tremolo solo, I got hold of the

arm, shook it and broke all six strings!!! Believe

me there’s nothing more useless than a guitar with

no strings—I just stood there and went `Argh´!. That

first guitar was a Guyatone—Hank Marvin had one for

a short while. Then I had a `Burns Tri Sonic´, which

was an awful thing to play, but it had a good jazz

sound on the front pickup. After that came a `Grimshaw´--the sort of poor man’s

`Gibson´--which I

traded for my first proper Gibson.

How were Ten Years After formed?

I was with a

band called The Atomites. Leo (Lyons) was playing

bass. He was the first bass player I met who was

keen on Bill Black; in fact, Leo is one of the few

players who can make an electric bass sound like a

slap stand up. So I was Scotty Moore and he was Bill

Black! We used to do `That’s Alright Momma´ and

stuff like that. We changed the name from the

Atomites to the JayMen, then to the JayCats and then

the JayBirds! The JayBirds got to be quite well

known in Nottingham in the early 60’s, and that

basically was the Ten Years After line up that moved

to London. But we still returned to do Saturday

night gigs in Nottingham!

…so you more or less turned semi-pro?

Well

yes,

sort of. You see, I was just waiting to get out of

school, because I was playing anyway and I was very

lucky with my parents, because I was coming home

from gigs at 1 am when I was only 14! I didn’t go

into an ordinary job; I’ve been a full time musician

since leaving school. At least it meant I could have

a sleep-in in the mornings! My parents used to ask

when I was going to get a proper job! The third time we went down to London, we got a

job in the West End at The Prince Of Wales Theatre,

so we were the band in the pub scene of `Saturday

Night and Sunday Morning´. That was quite good, it

meant regular money and enabled us to set up in

London, but the play only ran for five weeks, so

after that we ended up backing `The Ivy League on

the cabaret circuit. The door really opened for us when John Mayall

broke open the blues scene. We did a residency at

the Marquee club when we were known as `The

Bluesyard´, but we thought that name would tie us

down too much to blues, so we changed it to Ten

Years After. The Marquee gig led to the Windsor

Festival and then the whole London club circuit.

We got a record deal by word of mouth really. The

offer came through to our management for us to make

an album—in fact, I think we were one of the first

bands to make an album without making a single

beforehand. At that time. The music was described as

`underground´ and I quite liked that—the fact that

you don’t have to dress up to go on stage was

great!

To be able to go on in `T´ shirt and jeans and

tennis shoes—that was freedom! We used to wear these

little leather things and try to look smart before,

and I used to hate all that—although I was an Elvis

fan, I would never have dared to wear a lame´ suit

or anything like that!

How did your `superfast´ technique develop?

Basically it just came from the excitement of

playing live—the adrenalin. I used to hear tapes of

the band from the mixing desk after a show, and

sometimes I couldn’t believe it was me playing! I

really didn’t know I could play like that—Ten Years

After was all about excitement and energy. I

basically played guitar `from the hip´, an instinct

or reaction if you like, because I’m not one for

practicing, I’m a `jammer´. My attitude was to `go

for it´, and on a good night I could get it. I

sometimes didn’t know what I was doing and

occasionally would mess it up, but I’d bluff my way

through with conviction. It’s like the old story—if

you play a horrible note, play it again and people

will think you meant to do it! I think you improve

when you make mistakes; if you play perfectly all

the time, then you are playing too much within your

boundaries, it’s time to push the boundaries and see

how far you can get. All the work in a studio to do

an album, that’s real work, but the fun part is

going out on the road and playing live!

Talking of playing live, you did some `mega´gigs…

Woodstock was a particularly good memory for me. It

needn’t have been, had it all gone to schedule,

because we would have just flown in on the

helicopter and then flown straight out again, but

there was a thunderstorm just before we were due to

go on stage, so we had about three hours to wait. I

walked around the audience and around the lake, and

really got into it all—fantastic! When the movie of

Woodstock came out, about a year after the actual

festival, Ten Years After really took off. It was

our spot on the movie that accelerated the band up

to the 20,000 seater gigs instead of the usual 5,000

seaters. There isn’t much satisfaction playing the

big auditoriums though—you can’t hear anything,

can’t see anything. You just see the security men,

usually with cotton wool in their ears. That doesn’t

really encourage you to play your best! To me, the

Marquee is what gigs are all about; a thousand

people crammed together with sweat dripping down the

walls. It’s hot and the music is loud, and you can’t

get away from it—that’s really what I like. The

American clubs that I do are all like that. They’re

slightly bigger than the Marquee, but it’s all back

to the blues again and that’s how I cut my teeth.

Have you seen any artistes on your travels who

have taken your attention…?

Well I like Mark

Knopfler, his style is quite different and foreign

to me, but I like that fingerpicking. That’s my

hobby style really. I don’t think I could ever do it

professionally. I think Gary Moore is probably the

`hot boy´ right now, in fact, he came to a gig we

did in Ireland on a school roof! I met him about a

year ago and he told me he was in the audience in

the playground. He was at that impressionable

age—while I was watching Chuck Berry, Gary Moore was

watching Alvin Lee! He’s a very fine and technical

musician—he can play practically anything. It’s good

to be a motivator you know. I sometimes hear someone

playing my licks—the ones that have become a bit `trade-markish´--and that’s quite a nice

buzz, makes

you feel a bit like a teacher. And I think, as you

get older, that is one of the best things you could

possibly be, to pass on the things you know. Freddy

King was one of my favourites—one of the original

string benders! It’s a funny thing about string

bending, because I started off like Charlie

Christian with a 28 gauge wound third string—and

there’s no bending them at all! And then I heard

Freddy King and it was like a door being opened to

me—all these new licks waiting. The same with Chuck

Berry—playing solos on more than one note at a

time—that was a breakthrough that kept me busy for

about a year, exploring all the different

combinations. The more you know, it kind of gets

slower and slower—the less new things there are to

pick up. The hammer-on with the right hand was

probably the latest thing, but they’re getting fewer

and farther between—I’m happy now to stumble across

a new progression, maybe once a month or something.

But I notice on a couple of your guitars you have

Kahler tremolo systems, and I don’t think we’ve ever

seen you use one on stage. But I notice on a couple of your guitars you have

Kahler tremolo systems, and I don’t think we’ve ever

seen you use one on stage.

That’s right. Actually I

was a bit of purist before I got hung up on them,

but I used one in the studio and I wanted to get the

same effect live, so I put one on a stage

guitar—just in case. But I’m a convert now—put

Kahlers on everything, piano, saxophone drums…!!!

Have you done any session work with other

artistes or friends?

Well, Gary Moore lives nearby

and we’ve had a few jams—but nothing on tape yet.

But it’s funny being, for want of a better word, a

`legendary´ guitarist, I don’t get as much other

work as I’d like. People tend to think ´Oh, he

doesn’t need any work´ so they don’t ask me but, as

a matter of fact, I’d love to do it. So I’m putting

out a call in Guitarist Magazine—anyone who wants

some session work, I’ll do it—and I won’t charge a

fortune either!!!

And you have the advantage of owning your own

studio…

I’ve been interested in studio technique

since the very early days at Olympic—a sort of

amateur engineer if you like; I really enjoy it. I

get bands in here to do demos—and proper tracks as

well, but I’m an amateur engineer because I’d hate

for anyone to be relying on me. But occasionally, if

I’m not under pressure, I can get really good

sounds—but I can’t guarantee! I think having a

background knowledge makes you a better recording

musician, and it’s taken years because it is only

recently that it’s all started coming together,

logically. It’s always been a kind of mystery—and

that’s what makes it so interesting. In the early

studio days you used to go in to record, and they

wouldn’t even let you hear it back! They would say

`That was fine, now what else have you got…´ Having

this place is great for experiments and ideas; you

can just pick up your guitar, switch on and away you

go—instead of losing ideas. Really, for a

professional musician and a recording musician, it’s

down to the songs and the creativity. Playing is fun

and song writing is hard, actually creating music is

hard. That’s where the work comes in and where the

time is consumed. I’ve probably got about 500 hours

of great jams on 16 track; I’ve had all sorts of

great musicians down here, but we all play in E for

half an hour or A for half an hour. It’s some of my

favourite music, but you can’t do anything with it.

Do you try and escape from those common blue

keys?

Well yeah, that’s the whole trick. It’s

finding something that goes with E that isn’t A—but

sounds as natural, that’s the hard thing. You have

got to make it flowing and natural and not fall into

the three chord trap. Basically I like 12 bar and I

like three chords. The thing is to use four chords

and that’s where the jazz and the funk got me out of

that—an easy way out. I’m still trying to make basic

rock `n´ roll sound like 12 bar with three

chords—but not use those three chords! I’ve always

found that, no matter what you do performance-wise

in front of the general public, I’m always aware of

what other musicians think. Sometimes there will be

one guy in the front row and you can tell he’s a

guitarist because his eyes are transfixed on your

left hand! Suddenly I think I’d better watch it

because this guy is watching me very closely—so I’d

better come up with something good here…!

Presumably, when you do a gig nowadays, it’s

obligatory to pull out some of the old favourites?

Well, I enjoy it. It’s always been obligatory and I

revolted against it for a while. In fact, when I had

the `In Flight´ album, I did a set that had no Ten

Years After numbers in it at all—I thought I would

have a change after 8 years of the same material, so

I was playing funky and jazzy stuff with Mel

Collins. But I remember going to see Jerry Lee Lewis

in Birmingham and he did all country music—no Great

Balls Of Fire or any of the well-known stuff and I

was really upset. So, from that night on, I thought

maybe people who came to see me would be

disappointed if I didn’t do the favourites. From

then on I’ve never had any reservations about

playing them. I mean, if you’re making money, then

you’ve got to give people what they like. It’s fine

to be a musician but if the public are paying to see

you they want entertaining, and you have to play

what they want. Actually, that was quite a

turn-around for me, because I was quite a reluctant

entertainer for most of those Ten Years After

years—I used to play a bit begrudgingly sometimes. I

mean that happens; you get to the point where you

walk on stage and everyone is cheering before you’ve

even played a note. Some nights you would play

pretty badly, in your own estimation, and nobody

would seem to notice—other nights I would play

really well and no one would seem to notice either!

It’s a difficult pill to swallow: you begin to think

`What am I really doing—just being a cardboard

cut-out and going on stage to do these songs, like a

juke-box´. I think that attitude comes from doing

too much, because we used to work all the time and

had hardly any time to write songs, so the set

stayed pretty much the same for about five years!

But I’m enjoying it now, because I’m not working to

that intense level—I’ve actually enjoyed the last

five years touring without an album—it’s been

great.

You don’t have all those interviews and all that

circus thing to do, but the new album is out now so

I think I’ve got to go out and work a bit more. But

that’s good too, because you’ve got to stretch. I’ve

actually found a lot more enjoyment in playing now

that I’ve got back to the kind of gigs I like—and

the kind of music. It’s just taken me this long to

work it all out in my own head. I used to be out on

the stage wondering what I was doing it for. Now I

know what I’m doing it for, and that means a lot.

When there are times that I get a bit rough on the

road—and I love being on the road, but there are

bound to be times when you think `What the hell am I

doing this for?´ Really, you’ve got to be doing it

for yourself because if you’re doing it for other

people you start resenting it. If you’re doing it

because your manager has made you, then you start

not liking the manager, but I have a much more

mature attitude nowadays. But getting back to the

old numbers, they will all be in with the new set

from the Detroit Diesel album—Goin`Home, Good

Mornin´ Little Schoolgirl, and Help Me Baby. They

are key numbers in the set, because you have to open

with a strong number and then you can play a blues

or back off a bit—Schoolgirl is always a lift to

start things off. Love Like A Man is a very simple

riff that goes down a bomb—I meet lots of people who

tell me it’s the first thing they learnt to play on

guitar. It’s easy to play, but when you play live it

still works. I don’t know why it is, there is no

secret in any particular combination of notes, it’s

just certain notes together really click. I think

you can get over-complex and play something that

sounds good to us as musicians, but it goes right

over the heads of the audience—it’s what pleases the

ears that matters.

Well we are sitting here in your studio Alvin,

and I see the room is full of guitars, so you are

obviously something of a collector… Well we are sitting here in your studio Alvin,

and I see the room is full of guitars, so you are

obviously something of a collector…

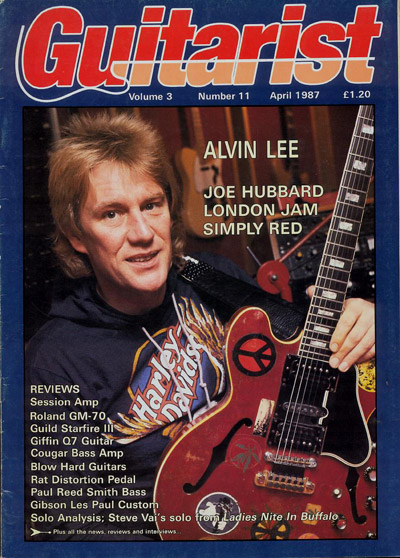

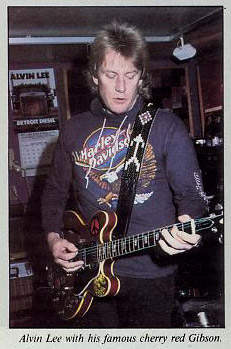

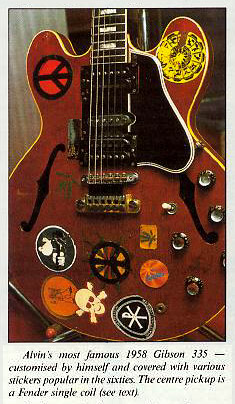

That’s right,

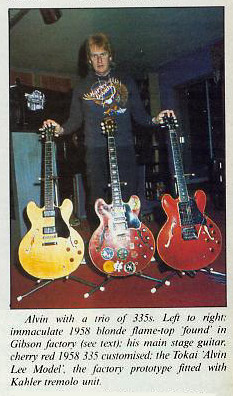

and here is my famous 1958 Gibson 335 that I bought

for £45 in Nottingham—best investment I ever

made—even had a fitted case!

How did it come to be covered in so many

stickers?

Well, they just got thrown on

actually.

But when I broke the neck at The Marquee, owing to

the ceiling being so low, I sent it back to Gibson

for repair and when it was returned, they had

lacquered over all the stickers—so they couldn’t

come off anyway!

You’ve done some work to the 335 yourself over

the years…

Oh yes, I’m a keen dabbler! I’m always

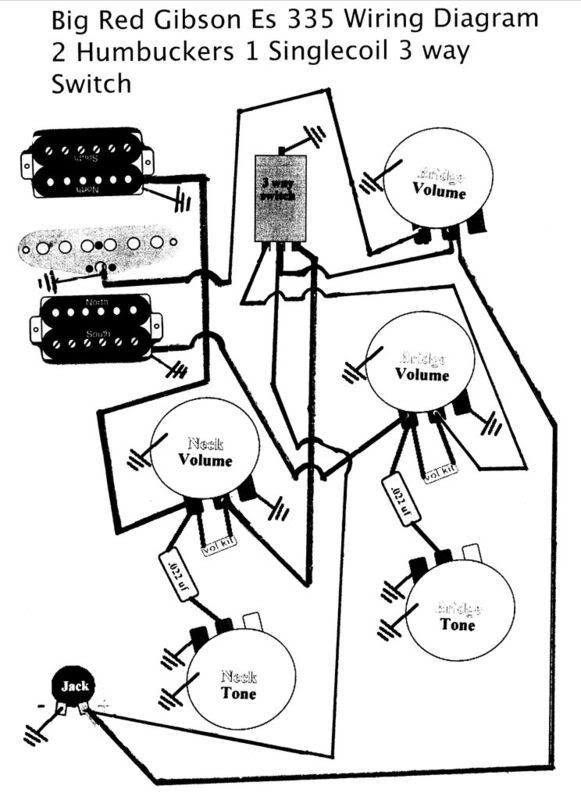

changing pickups and re-wiring. The Gibson has the

original 1958 PAF humbuckers with the covers removed, and a Fender pickup in the middle to give a

bit more top—it’s good for the studio—lots of cut

and fizzytop. I used to buy Hofner and DeArmond

pickups and mess about with those as well. The 335

is still my main guitar: I think it’s the size of

the body—it fits me quite well. I love to play

Strats but I prefer to play them sitting down for

some reason. I enjoy Les Pauls, but they feel too

small and heavy. I’m just used to the 335. I bought

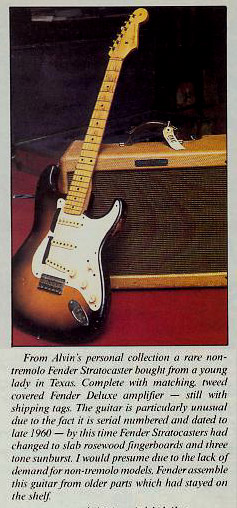

this old Strat from a girl in Texas, who took

lessons for a week and then put the guitar in the

attic, along with this lovely Fender tweed amp.

The

whole lot only cost 400 dollars; they didn’t seem to

value old guitars so much then. The most I’ve ever

paid is 1,400 dollars for this 1958 335, which was

`lost´ at the Gibson factory and found later under a

pile of old wood. It was cased, so it’s totally

unmarked with the most beautiful blonde flamed

top—just lost in the factory for twenty years! Dave

Edmunds is after it actually… When we were touring

the States, my guitar would be in the equipment

truck, and I wanted one to play in the hotel room.

So at the beginning of each tour, I would go into

stores and try find interesting guitars—like this

Gretsch Chet Atkins. It’s got a good acoustic sound

as well, so I could play it in the hotel room

without an amplifier—this was the days before

Pignose amps! The

whole lot only cost 400 dollars; they didn’t seem to

value old guitars so much then. The most I’ve ever

paid is 1,400 dollars for this 1958 335, which was

`lost´ at the Gibson factory and found later under a

pile of old wood. It was cased, so it’s totally

unmarked with the most beautiful blonde flamed

top—just lost in the factory for twenty years! Dave

Edmunds is after it actually… When we were touring

the States, my guitar would be in the equipment

truck, and I wanted one to play in the hotel room.

So at the beginning of each tour, I would go into

stores and try find interesting guitars—like this

Gretsch Chet Atkins. It’s got a good acoustic sound

as well, so I could play it in the hotel room

without an amplifier—this was the days before

Pignose amps!

When I got home to England, I would

just hang them up and buy another one on the next

tour and so on. I never really wanted or needed 40

or so guitars, it was just easier than taking them

back once you had got an American guitar over to

England. I’ve got about six 335’s, including a 12

string, and if I ever find a half decent red one,

I’ll get it anyway and try and make it into a stage

guitar. My original red 335 has done every gig with

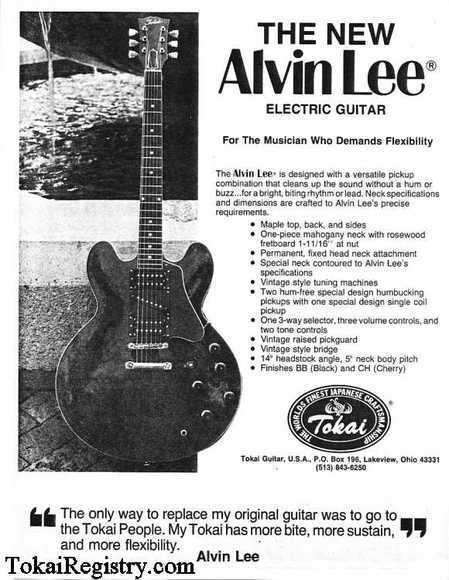

me, up until December of 1986, and then the Tokai

company came along and measured everything to make

an exact replica of it. To finish off I got Mark

Willmott, who does my serious guitar work, to fit a

Kahler and shave the neck a little. Tokai were going

to put this model into production--`The Alvin Lee

Model´ --but they have stopped the production of

semi-solids at the moment, so it could be another

rarity to hang on the wall.

Basically I’d like to

get together with some company and get a model into

production—I’ve never even had a spare stage

guitar,

I just take the one and change the strings before

the set. If a string breaks, it’s a quick drum solo

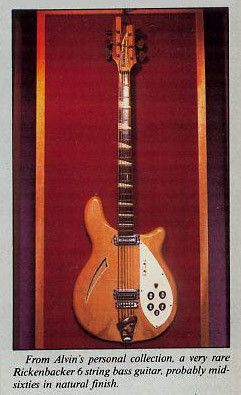

while I change it! I wanted a Fender six string

bass, but ended up with this Rickenbacker which is

quite rare and unusual. I’ve got a Wal bass which I

like—I’m quite keen on playing bass now.

What about your onstage set up, what happens

after the guitar? What about your onstage set up, what happens

after the guitar?

Curly lead…!! I tried those radio

transmitters once—for about an hour, until one of

the crew came along and said `Where’s your lead?

That’s not rock ´n´ roll´. I thought he was dead

right, so I scrapped it. I had the radio, but I was

still turning around and stepping over an imaginary

lead anyway!! It didn’t sound the same as a lead

though. You see my guitar is matched perfectly to

this old 50 watt Marshall I’ve got; it’s ancient! In

fact a guy came down here from Marshall –Mike his

name was—and he said it was built before his time,

he found a component in there he didn’t even know

about! I don’t know about pre-amps and foot pedals.

I think the answer is to get an amplifier input

level that matches your guitar perfectly. I use the

50 watt Marshall full up—I mean people used to think

we were loud because I used to use 10 Marshall

cabinets one time—but I only had the one 50 watt

amp. I liked the dispersion! I tried the 100 watt,

but it was too `middley´ I prefer the 50, flat

out—it’s great.

You’ve got a Roland guitar synth in the corner…

Yes, it’s a present from George Harrison. He got

bored with it—and I got bored with it too. It’s

fun.

But it’s more of a toy unless you know particularly

what you want to get out of it. Then I find you are

not playing a guitar like a guitar—it’s easier to

use a keyboard to get those sounds.

How did you manage in those early days when there

was no such thing as light gauge strings?

Because of my early jazz

leanings, I was quite late changing over. I just used a first string on the third or

something like that to start with, but I’ve always

liked heavy strings. The set I use now are 54, 44,

28, 15, 12, 9. I did a gig with Frank Zappa once and

at the end we decided to have a little jam, so I, so

I played bass and gave him my guitar—but he couldn’t

play it! The action was up a bit and he likes it

laying on the frets—one of the things I noticed

about Gary Moore, he has a high action and heavy

strings. I like a big heavy bass string to hit that

with gusto.

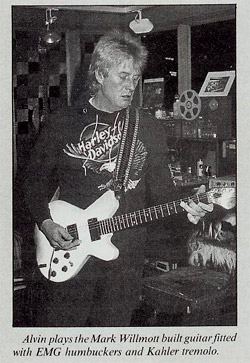

What about the guitar you used for the Roger

Chapman tracks?

It’s built by Mark

Willmott, but we

are still working on the shape—it’s not quite right

just yet. Actually we need a name for it, so if any

of your readers have a good idea let us know. It

gives a great sound, and I used a Rockman for the

tracks you heard—I think the Rockman covers most

needs—clean and dirty. I’ve got some interesting

little WEM Dominator amps—15 watt output with one

12´´ Celestion—sounds like a stack of Marshalls when

you mike them up. For live work though, it’s the

335—curly lead and the Marshall—no effects!

We’ve got two gentlemen here in the studio who

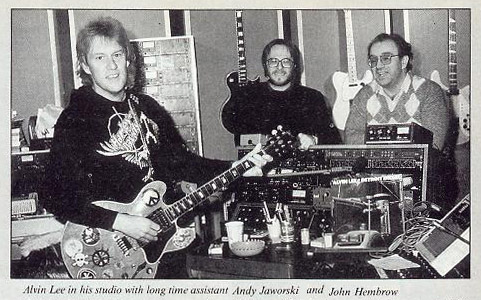

have been your assistants for how long?

Nineteen

years! John Hembrow and Andy Jaworski. John is my

tour manager and Andy is the sound man—they help

they help with everything—guitars, amps, door

hinges,

car repairs! We’ve been all over the world together

and we’re just off to Yugoslavia and Austria with

the three piece, then hopefully when the album is

released here, some UK dates. Who knows, we might

link up in the Blue Bore Café one night on the way

up to Newcastle! Just like the good old days… It’s

funny, I don’t know where to play in England—like

the Universities have probably never heard of me

these days—same with the little clubs—it’s

difficult.

Maybe it’s time to go out and educate the masses

again—not Ten Years After but Twenty Years After?

Could be the case—yes!! I think that’s it in a

nutshell. I’ve got to get out and about and be seen

again—I can’t think of anything better to do anyway—it

beats watching television, that’s for sure!

Article written by, Bob Hewitt

|