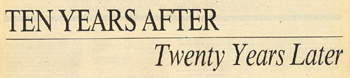

|

GOLDMINE

MAGAZINE, FROM OCTOBER 6, 1989

ABOUT

TIME

Although

several of the reformed rock groups

recording and touring the country in this

reunion year also played at what has become

1989’s big commemorative event, the 1969

Woodstock Music And Art Fair, only one

remains primarily identified with the event.

The Who and Jefferson Airplane both played

there, but it is Ten Years After, a band

that broke up fifteen years ago, that will

always remain tied to its extended treatment

of lead guitarist Alvin Lee’s “I’m

Going Home,” as shown on the split screens

of the Woodstock movie released a year after

the event.

A

closer examination of the band’s career,

however, reveals that that performance,

while not unrepresentative of the group’s

music and concert work, gives us only a

small reaction of Ten Years After’s

importance to rock history. And with a new

album, aptly titled “About Time” and

featuring the group’s four original

members, there may be some history yet to be

written.

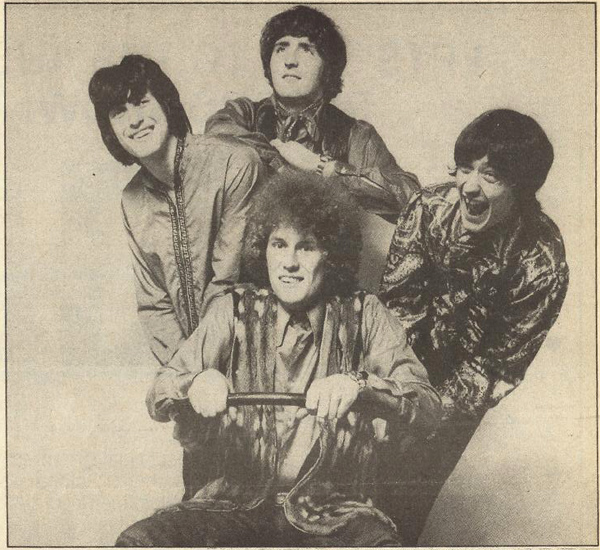

Ten

Years After originally appeared in clubs in

London as part of the ongoing blues revival

that had already given birth to the Rolling

Stones after having been founded by such

figures as Alexis Korner and John Mayall.

Alvin

Lee, born December 19, 1944 in Nottingham,

and bassist Leo Lyons, born November 30,

1944, in Bedfordshire , were childhood

friends who grew up together in Nottingham.

Both were playing by their early teens,

combining American blues and jazz influences,

and Lee even backed John Lee Hooker at the

Marquee Club in the early 60’s.

In

1964, with Lyons playing drums, (not true at

all according to Leo 2007) they performed in

Hamburg, West Germany and elsewhere in

Europe as “Britain’s Largest Sounding

Trio.”

Back

in Nottingham, under the name “The

Jaybirds”, they acquired Ric (no relation

to Alvin) Lee, born October 20, 1945,

Staffordshire as drummer, from “The

Mansfield’s” in August 1965. In 1966,

they moved to London, where they picked up

work in clubs as well as accompanying the

play “Saturday Night and Sunday Morning”

and touring as backup group to the Ivy

League. By November, they had been taken on

by manager Chris Wright, whose agency with

Terry Ellis, named Chrysalis ( Chris /

Ellis), would have a major impact on their

career. They also acquired keyboard player

Chick Churchill (born January 2, 1949, in

Flintshire). (not true as Chick was born

in…)

After

a single gig under the name “The Blues

Yard”, they became “Ten Years After”.

In the spring of 1967, they were overheard

by the Marquee Club’s manager, John Gee,

playing Woody Herman’s “At The

Woodchoppers Ball.” This led to a

residency at the influential club and to the

band’s signing to Decca Records, which

would release their recordings on the new

“Progressive” Deram label.

The

group’s first, eponymous album was

released October 27, 1967, featuring both

standards like Willie Dixon’s

“Spoonful” and originals by Alvin Lee.

It didn’t chart, and neither did a one-off

single, “Portable People” and “The

Sounds,” issued in February.

For

so active a road band, it was appropriate

that their second album, “Undead”, was

recorded live, at Klooks Kleek Club.

Featuring “At The Woodchoppers Ball,”

“Summertime” and

“I’m Going Home,” it was

recorded August 16, 1968 and issued

September 21. In Great Britain, the album

reached number 26, while in the U.S. it got

to number 115.

By

this time, the band had begun to tour the

U.S. at the behest of Bill Graham, who

arranged gigs at his Fillmore clubs. By the

time of their demise, they would claim to

have done more U.S. tours – 28 – than

any other British Invasion Group. Alvin Lee

now claims more than fifty U.S. tours

himself.

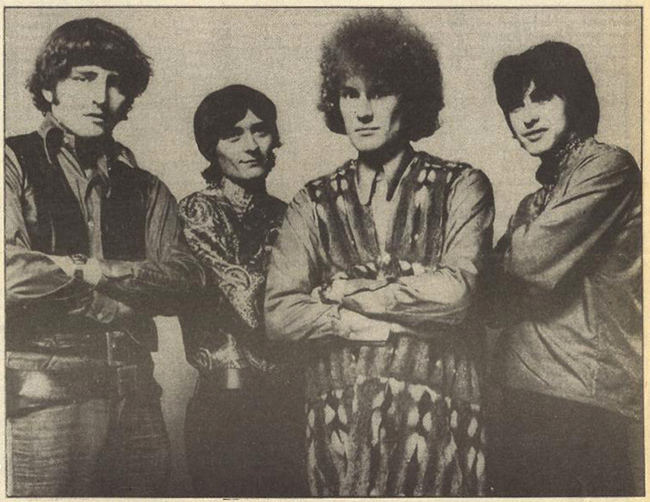

The

touring would affect Ten Years After’s

U.S. popularity drastically, but the

influence of America – especially the

psychedelic influence which also had its

impact on the band’s music, as can be

heard starting with their third album, “Stonedhenge”,

recorded from September 3rd to

the 15th 1968 and released

February 22, 1969. Continuing the group’s

gradual sales increase, it peaked at number

6 in the U.K. and rose to number 61 in the

U.S.

A

contract negotiation saw the group signed

directly to Chrysalis, which licensed their

records to Decca. In later years, when

Chrysalis became a record company, many of

Ten Years After’s albums would be

reissued on that label.

In

June, the group recorded a new album,

“Ssssh” and then returned to the U.S. to

tour, hitting the festival circuit. They

played on August 15th and Ssssh

issued the same month became their biggest

selling hit yet, reaching number 4 in the

U.K. and number 20 in the U.S.

Their

next album was “Cricklewood Green, a

slight return to the blues, albeit

psychedelic blues, which was issued in April

of 1970, again going to number 4 in the U.K.

and hitting number 14 in the U.S. with a

single,

“Love

Like A Man,” which reached number 10 in

the U.K. but only got to number 98 in

America.

With

the release of “Woodstock” the movie in

August of 1970, Ten Years After became a

major concert attraction, though its

relentless schedule was beginning to hurt

the quality of its record releases.

“Watt”

was issued in December of 1970, and got to

number 5 in the U.K. and to number 21 in the

U.S. indicating that, despite Woodstock, the

bands record sales were levelling off. The

band then took three months off the road to

prepare its next album, which would be its

first under a new contract with Columbia

Records.

“A

Space In Time,” featuring a more

electronic sound and more reflective songs

from Alvin Lee, was issued in August and

became Ten Years After’s biggest U.S.

seller, going gold by December and producing

the Top 40 hit “I’d Love To Change The

World.” It was to be, the band’s

commercial peak.

Deram

picked this exact time to issue a

compilation of unreleased British tracks,

called “Alvin Lee & Company,” which

reached number 55 in 1972. The bands

official follow up was “Rock & Roll

Music To The World, and was issued in

October of 1972 and only got to number 43

– followed closely by their “Recorded

Live,” album (known as the official Ten

Years After “Bootleg”) and was released

in June of 1973 – it reached number 39.

At

this point, the group took six months off

for solo projects, among them Alvin Lee’s

album with Mylon LeFevre , entitled “On

The Road To Freedom,” which reached number

138 early in 1974. And by that point, Ten

Years After was in the studio once again,

but by the time they’d finished recording

“Positive Vibrations,” they had all

decided to disband, playing a farewell gig

on March 22, 1974, at the Rainbow Theatre in

London.

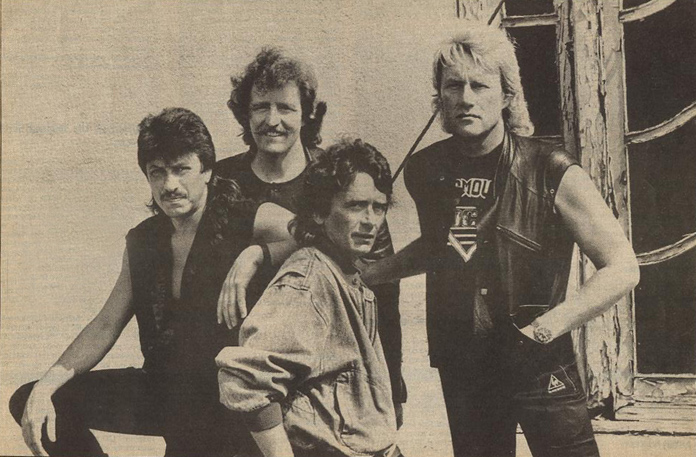

Not

surprisingly, their final album only reached

number 81. The following year, Ten Years

After reformed for a single lucrative U.S.

tour in July and August, and that was it.

Most

visible since the split has been Alvin Lee,

whose bands, including one called “Ten

Years Later,” have put out albums

periodically. There have also been periodic

Ten Years After compilations, and in the

last year Decca has issued the first three

albums on CD, while Chrysalis has put out

the rest, so that the band is one of the few

1960’s acts to have its entire catalogue

in print and on CD.

And

now comes “About Time,” which, on a July

day in 1989, brought Ten Years After’s

four original members (plus their

manager Derek Sutton) together to sit in a

hotel room in front of “Goldmine’s”

tape recorder and talk about their past,

present and future.

Goldmine:

Let’s start at the period in 1966-1967 at

which the band got the name Ten Years After

and signed to Decca Records.

Alvin

Lee: Originally, it was the Jaybirds.

That was the band with me and Leo. For a

short period, we were called the Blues Yard,

(for only one or a few gigs at that) then we

decided that tied us down to one kind of

music too much. The first happening thing in

London was the Marquee residency and

that’s when we decided we needed a name to

take us through into the 1970’s as it were.

Ten Years After has got no real meaning,

it’s just a nice phrase. It’s not

particularly 10 years after anything. We did

realize that by accident it was 10 years

after Elvis Presley became famous, to us in

England, anyway. But we were nearly called

“Life Without Mother”. That was the

second one / choice.

Ric

Lee: Yeah, it could have been worse.

Alvin

Lee: (no relation to Ric) I quite like

that, actually . So, the name was picked and

the Marquee residency led—it was the

situation in those days where we were

getting a good name on the club circuit in

London and we got approached by Decca

Records. Did we want to make an album? And I

think we were one of the first bands to

actually make an album first, because in

those days you used to make a single and if

it did any good then they’d let you make

an album.

Ric

Lee: (no relation to Alvin Lee) Funny

thing about that was we did an audition for

them a few weeks before, didn’t we?

Alvin

Lee: We actually did an audition for

Decca and failed it, and then they called us

up a few months later and said, “We want

to make an album with you.” We just got

hooked up with the wrong A&R man when we

did the audition.

Goldmine:

Tell me about Mike Vernon, the producer of

your first three albums.

Alvin

Lee: He was kind of an in house producer,

to be honest he wasn’t that active. He

turned up and helped out. He wasn’t a

great force. He admitted himself that he

didn’t really understand what we were

trying to do.

Ric

Lee: Mike was a very pure blues fanatic.

Alvin

Lee: Yeah, he was a pure blues fanatic,

and remember the “blues boom” that John

Mayall started? That was probably the

turn-around for Ten Years After to take off.

Because I’d been brought – my father

used to collect chain gang songs, very

ethnic rural blues stuff, and of course, for

the occasional one o’ clock set in the

morning when you do three sets a night,

we’d do a bit of the blues and a bit of

jazz; there was no real outlet for it. And

then, when the blues boom happened, suddenly

I had a whole list of, a repertoire of great

blues songs which I could start putting in

the set.

Ric

Lee: Plus the rock `n´ roll, Little

Richard stuff we’ve always loved.

Alvin

Lee: Right, in other words, Chuck Berry,

Jerry Lee Lewis, early Elvis, and blues.

Goldmine:

The reputation of the band was

always that it had a much more diverse set

of styles than many of the blues bands of

that time.

Ric

Lee. I think that’s the different

people in the band. As Alvin just outlined

his influences, mine were jazz, like Joe

Morello, Buddy Rich, those types. Leo’s

were Scott La Faro in those days.

Alvin

Lee: Bill Black and Scott La Faro!

Ric

Lee: He was the bass player with Bill

Evens. Scott was killed in an automobile

accident very early on, unfortunately…and

Chick Churchill’s influences were, Oscar

Peterson, and that area, and I think when

you put those four influences together,

that’s why you get the amalgam you get.

Alvin

Lee: I did used to like Count Basie

quite a lot too, I think the swing thing we

all came together on that.

Ric

Lee: And George Benson, before anybody

ever heard of him.

Alvin

Lee: And Brother Jack McDuff. At that

time, when we were teenagers in the 1950’s

there wasn’t really that much, apart from

the blues and very ethnic R&B, before

we’d heard of Chuck Berry. We were mainly

listening to American swing jazz for our

inspirations. So we had a four-piece band

and we were playing Count Basie numbers,

which didn’t sound much like Count Basie,

but our own style came out of it. And

“Woodchoppers Ball” was a Woody Herman

song. In fact, we used to do backing work

and back cabaret artists and when they went

off waving, we used to play “Woodchoppers

Ball.” And sometimes we’d carry on for

five minutes and go down better than the

orchestra we were backing.

Ric

Lee: We actually got two gigs out of

that, on our own, just on the strength of

doing that as a play-out song for another

band. But we used to do it at a rate of

noughts’ as well. It was about fifteen

times faster than Woody Herman!

Alvin

Lee: I remember John Gee suggested that

we do a concert with Woody Herman and play

“Woodchoppers Ball” together. I said,

“I don’t think that’ll work, somehow!”

Goldmine:

Tell me about Ten Years After, the first

album.

Alvin

Lee: The first album was, in fact,

basically our live set. We didn’t have to

think much or write anything. And the album,

I think, was recorded in two days, one of

those situations where you record the song,

and say, “Thank you,” and they don’t

even let you listen to it, and then you just

went on to the next one.

Ric

Lee: We had a problem with “Help Me,”

didn’t we? We were trying to get the

atmosphere of that onto the album. We did

about three takes of it, and the third take

was really happening. It’s a very, very

slow number. It’s very difficult to get

the feel of it in the studio as opposed to

live. And we came back and the tape operator

had wiped the first one clean – (erased it

altogether).

Alvin

Lee: I’ll tell you, it was 10 minutes

long; they weren’t used to long numbers,

and what they used to do was record one

number on this side of the tape and turn it

over, and record another number on the other

side. And the two overlapped, because we

used to do long numbers. We were the cause

of them stopping that particular way of

recording.

Goldmine:

Did you have any problem moving from being

exclusively a live band, to now doing studio

recordings?

Alvin

Lee: Oh, yeah. Straightaway, the technicians

then weren’t used to – you couldn’t go

in with four Marshalls. It was un-heard-of.

They’d think you were a maniac and

they’d always get you to play through

smaller amps. So we had a hard time just

getting our own sound happening, because

they encouraged you to play quieter. Also,

they want you to do the backing track and

then they go back and you overdub the vocals.

The first time I’d done that…lose a

little of the feel by doing that, too.

Ric

Lee: Also, drum-wise, you’d only have

probably two mikes live, one overhead and

one on the bass drum, which tends to get a

better balance across the kit, on the top of

the kit, on one mike, if you place it

correctly. In fact, I found out, Terry

Manning who was just on the new album, (Ten

Years After – About Time – as the bands

producer) was telling me that he engineered

the Led Zeppelin 3 album, and John Bonham

insisted on having two mikes on the kit when

he recorded. He said, “I’ll get the

levels, you place the mikes to get it

right.” Which I think accounts for the

drum sound he got on the albums.

Alvin

Lee: That’s right, you’ve got to

control your own dynamics.

Goldmine:

I assume, being in the studio for the first

time, though, this was the sort of situation

where, pretty much, the engineers were

setting things up and more or less telling

you.

Alvin

Lee: Yeah, they just said, “You just

play and leave the rest to us.”

Ric

Lee: Which is your first mistake.

Alvin

Lee: And from doing that, then we

started to experiment ourselves, and take

more time and get more complicated , which

finally leads up to the situation today

where some bands take a year to make a

record. We never got that bad. I think that

eight weeks is a maximum. I’ve seen a lot

of bands, you get through two albums and

you’re doing your live set, you record

your live set, then you have to start

writing new material and often you can see

bands start to droop a little because

you’re playing stuff you’ve had in your

set for five or six years, and it’s very

rehearsed and very tight, and basically you

just play it and it’s recorded as it is.

But then you get to the point where you’re

writing material and you play and you want

to hear it back and see how it sounds. It

gets to the point some bands start writing

in the studio, which is very dangerous,

because it can go on for months, that way.

The first two albums were easy, then you

have to start thinking.

Goldmine:

You had to go from being a band that played

primarily cover material, to being one that

played primarily original material. Was that

a natural transition for you?

Alvin

Lee: It was, really, but as I say, when

you’re on the third album and suddenly you

need eight new or ten new songs, you can do

a couple of covers and then try to write the

rest yourself; that’s a vast departure. I

think on the first album I wrote about three

or four, maybe five, (one of which was

co-written by Chick Churchill, and one by

engineer Gus Dudgeon), which is not to hard.

When you have to come up with a whole album

concept and everything else…

Ric

Lee: It must also be difficult to get

stuff with a band that’s got as diverse

influences as we had then, getting stuff

that suits everybody to play.

Alvin

Lee: It was trial and error, to be

honest. We were experimenting a lot in the

studio. We’d say, “Let’s try a

country-style number,” “Let’s try a

slightly funky number.” We weren’t

saying, “This is definitely our music.”

Was the second album Undead? (asked Alvin).

Ric

Lee and Goldmine: Yes

Alvin

Lee: That was recorded live at Klooks

Kleek and I remember when it came out I was

delighted. I heard it in L.A. when we came

here on the first tour (1968 – Fillmore

West) and I thought, “Well, that’s it.

What can we do? That’s everything.

That’s probably as best as I’ll ever

play.” I thought it really captured the

band at its best. And I kind of had an

inkling that there were going to be problems

in the future recording, because what was on

those two albums encompassed

everything the band could do.

Goldmine:

Up to that time

Alvin

Lee: Yeah

Goldmine:

The next album, “Stonedhenge,” sounded

like a movement in the band’s sound to

different kinds of things.

Alvin

Lee: That was the first experimental

album, and also the influence of the West

Coast. The San Francisco thing, the

Jefferson Airplane and the Grateful Dead,

were already creeping in there, with the

strange sound effects and oddities going on.

Ric

Lee: That was the album, also, we all

did a separate track, which was a bit of a

giggle.

Leo

Lyons: Twenty years later, perhaps, not

so much of a giggle!

Goldmine:

It was very much in keeping with the times.

Leo

Lyons: Yes, it was

Alvin

Lee: Absolutely.

Ric

Lee: (speaking to Alvin) They tried to

get you to do a mini-opera at one point,

because the Who were doing it. Didn’t they?

Alvin

Lee: Yeah, it was mentioned. I think it

was good that everybody had a little chance

in those days to do something special, and

different, as well. What we were doing with

those albums, because of the psychedelic

kind of influences, you record different

songs, but then you try and tie it together

and make a concept, so you make the whole

album like a “trip”. So that one side

would be a twenty minute piece, although it

may be five or six different songs in it,

and we’d link them up with sound effects

and try and make a little adventure out of

it.

Goldmine:

One of the things too, that was happening at

this time, in a career sense, that I note,

is that you finished a contract with those

three albums.

Ric

Lee: No, the contract was for six albums.

The other three were on Decca, as well.

Leo

Lyons: To a certain extent , you’re

right, because there was a production

company that came in between, so it was the

formation of Chrysalis Productions. When we

got a production deal with Chrysalis

between us and Decca, we were allowed

to record whenever we wanted to, with a

budget. Prior to that, we were told when to

record, how long we were recording, and more

or less we had to record at Decca studios.

So we moved over then to an independent

recording studio called Morgan Studios, and

it’s now called The Workhouse. And that

was an eight track. So the “Ssssh” album

was the first one that was done on the

eight-track. So Ssssh for us was the turning

point.

Goldmine:

By this point, also, the band was growing in

popularity. Did that put greater pressure on

the band? Ssssh came out just after you

played Woodstock.

Alvin

Lee: Woodstock was not a particularly

– it was an event, obviously, we were

aware when we arrived. But we weren’t

ready for any event, it was just another

name on the date sheet.

Ric

Lee: We’d done a bunch of quite large

festivals. It was just another festival.

Alvin

Lee: In fact, we weren’t even that

aware that it was that different when we

left there. Obviously, it was special, but

we weren’t aware that it was going to be

remembered so strongly. Had it not been for

the rain storm, we’d have probably flown

in by helicopter, played, and gone out again

within two hours and probably would never

have even seen it. But we were about to go

on and the rain storm broke. There was no

way anybody could play with the sparks

flying up on stage. The rain storm was

actually the highlight of Woodstock for me.

I thought it was better than all the bands.

There’s no way half a million people can

run for shelter, so they just sat there and

started singing, and I took a walk around

the lake and kind of joined in with the

audience and experienced it first hand,

which was good.

But

we didn’t play that well at all, because

when we finally did go on there was a lot of

brouhaha, because nobody wanted to go on

first due to the risk of shock, and I think

we took the plunge eventually and said,

“Oh, what the hell. If we get electrocuted,

we’ll get good publicity.” And we went

out and actually had to stop playing during

“Good Morning Little School Girl” and

re-tune because of the atmospherics. The

storm had done so many changes in the

atmosphere, the guitars went way out of

tune. I actually had to say, “excuse us, but we’ve got to stop and re-tune.” The audience

didn’t seem to mind; they were just having

fun anyway. But it wasn’t particularly a

good gig, playing wise, we didn’t rate it

at the top. It’s all in retrospect that

it’s such a huge event.

Goldmine:

One of the things, obviously that had a big

effect was when the Woodstock

movie came out a year later.

Ric

Lee: I think the pressure probably came

then.

Goldmine:

Was there a reaction immediately after the

festival?

Alvin

Lee: Not at all. We went on for a year

playing the same three to five thousand seat

venues. When the movie came out, we suddenly

shot up from 5,000 seat venues to 20,000

seat venues.

Leo

Lyons: I think what happened with the

movie was, it opened up all the small towns

in between the large towns we were already

playing.

Alvin

Lee: It crossed us over to the masses

rather than a cult following thing. It was

the end of the underground. A lot people say

that Woodstock made Ten Years After, but it

only catapulted us into that mass market and

in a way it was the beginning of the end.

Going into the ice hockey arenas, where you

can’t hear much, the sound’s terrible,

you can’t see the audience, it wasn’t

that much fun and it was a decline of

enjoying touring as much as we had done

previously. Also, the sad thing about

Woodstock it seemed it was the peace

generation all coming together, and then

they all went back home again, and never got

together again, as it all dissipated

afterwards.

Goldmine:

By talking about Woodstock, we’ve

skipped over the next album, Cricklewood

Green, which almost shows a moving back

towards blues or a more basic sound.

Alvin

Lee: It was still experimenting, but I

suppose we did start looking for our roots.

We didn’t want to get too far from the

roots. Cricklewood Green had “Year 3,000

Blues.” “I thought that was quite an

innovative song at the time, a blues based

on living in the year 3,000. Automatic

bloodhounds chasing people.

Leo Lyons: I think by the time of Ssssh and

Cricklewood Green we’d been exposed, quite

overexposed, to the American drug culture of

the time, too and I think that had an

influence on the albums.

Alvin Lee: On Cricklewood Green, at one

point, “Working On The Road,” which is

still one of my favourite songs, actually,

the tape slurs. It slows. Somebody leaned on

the tape machine when we were recording it,

and nobody even noticed at the time! So that

gives you a clue as to what state we were

in. Producers, engineers and band, no one

noticed it.

Goldmine:

There’s also a fair amount of quieter

music that you play on these albums, Ssssh

and Cricklewood Green, and the next one,

“Watt”, and in some cases slower music.

I wondered if that was a reaction since

there was so much writing about the speed at

which you could play.

Alvin

Lee: Yeah, I was kicking against that

criticism. In retrospect, I shouldn’t have

done that, but in those days I hadn’t

quite got my professional opinions sorted

out, my own attitudes. I was having a few

personal problems. I was starting to become

marketed, and I felt like a box of

cornflakes, and I wanted to be known as a

musician and not a pop star. Now you’ve

brought that up, that’s the first time

I’ve realized that was the period that

started. And probably I wasn’t too aware

of it at the time, but I was definitely

having thoughts in that area.

Goldmine:

Part of the effect of the Woodstock film was

to separate you out as a celebrity apart

from the group.

Alvin

Lee: Yeah,, we had always been a

communal band, and I was trying to kick

against that to some degree. I was actually

trying to de-escalate the “getting famous”

aspect.

Leo

Lyons: Which probably made it even worse.

Alvin

Lee: Also, you’ve got to remember, for

the idealistic 1960’s, it was also very

un-cool to be rich and famous. It wasn’t

one of the things we were striving to be. We

were striving to be credible musicians, much

more than trying to be pop stars. I’ve

never wanted to be a pop star, it was never

an ambition, and it seemed to be happening,

and I was kicking against it. I was kicking

against the criticism. People were saying I

was just a flashy, fast guitarist that

didn’t really have any taste and

couldn’t really play, and that was

upsetting me. So I suppose that was all

coming into the music.

Goldmine:

One album that stands out is “A Space In

Time”

Leo

Lyons: Well, that was a new contract.

That had a lot to do with it.

Alvin

Lee: Ah, but remember, we’re talking

of working on the road, which was the Ssssh

album, “Working on the road for fifteen

years, blowing my mind and blasting my ears”

(Working on the road is from Cricklewood

Green), and I was basically saying,

“It’s time to take a break.” And I was

campaigning for a break, because in those

days, we would do like a ten week tour of

America, come back to England for three days,

then do a five week tour of Germany, then

another three days off, then onto

Scandinavia and Italy, and after that

somebody say, “You’re in the studio next

week for the next album.” And I was

writing songs in the taxi on the way to the

studio, and not really having any time. Watt

was definitely suffering from no time to

write. In fact, even the original title –

was suppose to be called “WHAT”

and not “WATT” – but it came out as

the latter.

Leo

Lyons: Ten Years After What, wasn’t it?

Alvin

Lee: I eventually dug my heals in and

said, “I’ve just got to have some

time.” And I wanted six months off, which

was ludicrous. I think it ended up being

about three or four months off. It gave me

time to sit down with the acoustic guitar

and write some good songs, and I think “A

SPACE IN TIME” was the culmination of that.

A bit of time and there was the space to

write A Space In Time !

Chick

Churchill: That was why it was called

that, is it? I never knew.

Alvin

Lee: I think “A Space In Time” is

still my favourite Ten Years After album,

because we had time to work on it. “I’d

Love To Change The World” was that on “A

Space In Time?” asked Alvin.

Goldmine,

Ric, Lyons, and Churchill: Yeah

Alvin

Lee: I was embarrassed about that song

because I don’t like preaching in music. I

like music to be apolitical and I thought I

was maybe pushing my luck. To start off, I

was criticizing freaks and hairies in the

first line, and I thought, “ I’m going

upset a lot of people with this song,” and

I very nearly didn’t even put the song

forward. But it was a good song and it’s a

good job I did in the end. But I don’t

think it’s a typical Ten Years After song.

In fact, we never have played it live.

Sutton:

Much to the management’s disgust!

Alvin

Lee: The record company would come to

the gig and say “When are you doing your

hit?” And I’d say, “We don’t play

it.” “What? I said, “What’s the

point? It’s a hit already.” But, you

know, it was evident that people didn’t

come to the concerts to hear us play the

records, they come for the whole emersion in

the live concert thing.

Goldmine:

Is there a point here where there’s a

diversion between the albums and the live

gigs?

Leo

Lyons: Very much so, yes

Ric

Lee: Yeah, Right

Alvin

Lee: What album was “Choo Choo Mama”

on ?

Leo

Lyons: The live one.

Chick

Churchill: Live.

Ric

Lee: No, Rock and Roll Music To The

World.

Alvin

Lee: And that was the one after “A

Space In Time” and after the “I’d Love

To Change The World” and we didn’t play

it live. After that embarrassment, (Columbia

Records president) (Clive Davis) actually

picked a song, I don’t know which one it

was…

Chick

Churchill: “Tomorrow I’ll Be Out Of

Town.”

Leo

Lyons: “The Positive Vibrations”

album you mean. What a wonderful title.

Alvin

Lee: A very inept title, in fact. That

was the least positive thing we’d done.

Goldmine:

I guess the band had broken up by then.

Ric

Lee: It almost didn’t get finished.

Alvin

Lee: Of course we were also going

through the Country House Syndrome there. We

all had nice houses in the country and were

starting families and things like that and

there wasn’t really that much will to go

out and sit in the Holiday Inn for six

months.

Leo

Lyons: Funnily enough, there were one or

two tracks on the “Positive Vibrations”

album that I quite liked, some of the rocker

tracks. The Little Richard number, “Going

Back To Birmingham,” I quite liked that

and one or two others.

Alvin

Lee: Also, the other syndrome of a band

breaking up was that we were all building

our own home recording studio’s and nobody

wanted to go out and play, we all wanted to

stay in and make our own music. I think

it’s a natural thing to happen. I think we

just weren’t communicating. We’d just

spent all those years working together and I

think quite naturally we all just drifted

apart a bit, and started to find other

interest besides the band.

Sutton:

That tour you did, that 1975 tour, was a

very big tour, and then you just stopped

touring.

Alvin

Lee: We were just bribed into doing that

tour. We had broken up by then, we were just

bribed to go and do one more.

Sutton:

But it was enormous and it was a huge tour,

and then you stopped touring, and it was not

like a lot of other bands, where it gets

worse and the audiences get fewer and then

suddenly it falls apart.

Alvin

Lee: I think in a way, it was quite

fitting that we finished then, because we

were always very honest. It was a very

honest band, there was no bullshit, no

hyping, and really, the honesty was going

out of it, and we got disenchanted with that.

We were going out and playing automatically.

I think I started quoting the band as being

“a travelling jukebox.”

Goldmine:

I think “honesty” is a good word here,

because it would be natural that there would

have been pressure on you (Alvin) to hire

some people and call it Ten Years After and

go out there.

Alvin

Lee: Yeah, it was suggested at the time.

Goldmine:

You called the band Ten Years Later.

Alvin

Lee: Yeah, but that was considerably

later, anyway.

Ric

Lee: That’s because I sued him! (Laughter)

Goldmine:

There’s a long time between that break-up

and now.

Leo

Lyons: Fourteen years. The positive

thing of Woodstock – we’ve talked about

all the negative aspects of it – is, that

is probably the reason why we’ve got the

opportunity, in many respects, to be able to

start all over again.

Goldmine:

What brought about the reunion?

Alvin

Lee: It was sparked off by a German

promoter who called me up and said he’d

like to book Ten Years After, the original

band, for four festivals in Germany, which

was last summer 1988, which then prompted me

to call `round the guys, and say, “How

about it!”

Goldmine:

The new album, “About Time” came out on

August 22, 1989. Is there a tour?

Alvin

Lee: Yeah, it starts on October 1st

U.S.A.

Article

Written By William Ruhlmann

|