|

|

i

n t e r

v i e w

ALVIN

LEE

"My

heroes were the blues players ... you sit down with a bottle of

Scotch ... playing a funky blues club with lots of cigarette smoke

and booze - singing the blues."

Ten

Years After's

self-titled first album was released in 1967, but 1969's Sssh

was their break-out release following their appearance at the

Woodstock music festival. Alvin Lee's blazing blues-inspired licks

on "Going Home" in the documentary film chronicling that

historic event introduced him to a wide and appreciative audience.

After the British band's demise, Lee carried on with a critically

acclaimed solo career and occasionally Ten Years After would regroup.

NEON's Lorry Doll met up with Lee at Chrysalis Records New York

offices in 1989 right after the release of the Ten Years After album

About

Time. |

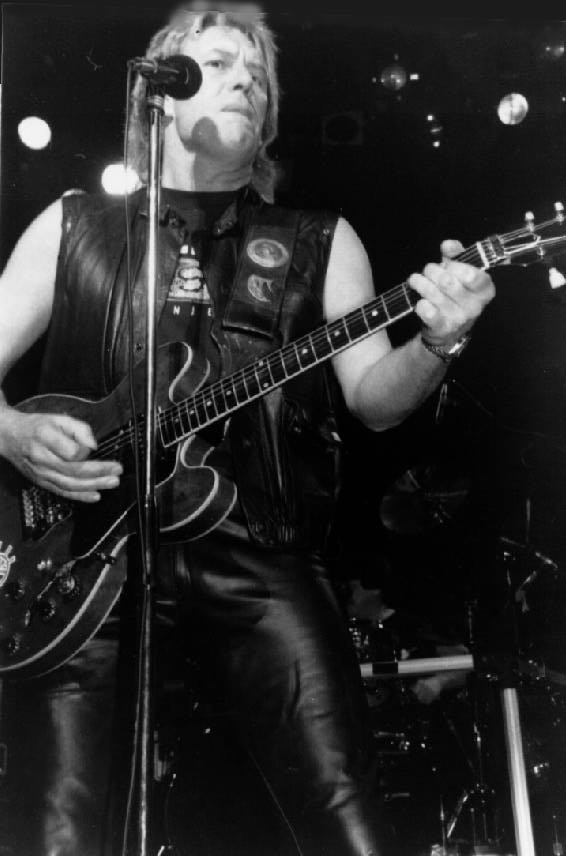

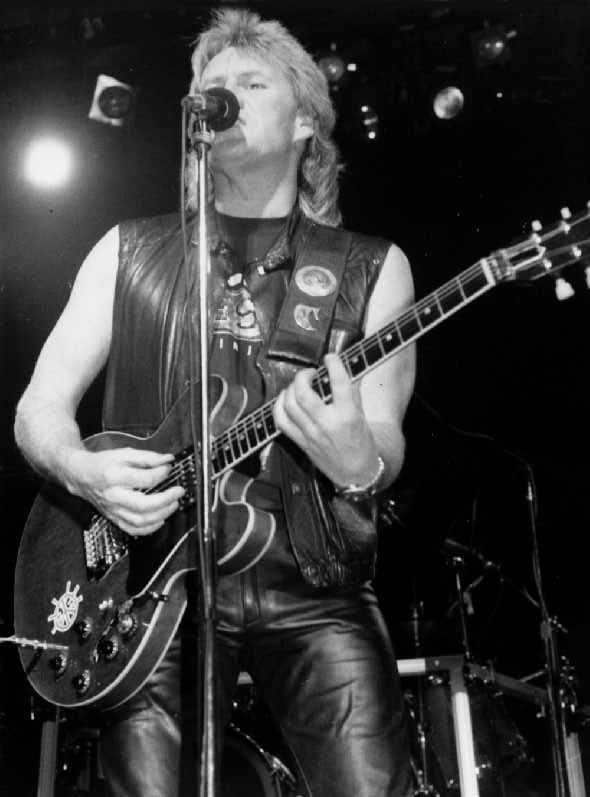

Photo by Lorry Doll |

Lorry Doll:

I like your new album a lot.

Alvin Lee: Thanks a lot, so do I.

You did it at Ardent

Studios in Memphis. You like Memphis?

I love Memphis. I suggested we do it there with Terry Manning, he

works out of there a lot. Personally, I thought I always wanted to

go to Graceland and actually I achieved an ambition there. A friend

of mine lent me a big 'ole Cadillac and I drove in the front gates!

And of course Beale Street was a lot of fun. We were jammin' down on

Beale Street after the sessions at a place called Rum

Boogie, with the house

band, Dominick. . . damn I wanted to give 'em a plug and now I

forgot their name!

How long were you in the

studio?

Ten weeks all together. Half that time it was scheduling the tracks

we didn't record. We had about fifty tunes. Everybody in the band

brought songs. We thought the fairest thing to do was let Terry

Manning pick the songs. We did fifty demos and let him pick ten out

of that. He picked about sixteen, seventeen songs and we tried them

live in the studio. When you record, some songs get better some

don't. Most of the time, probably four weeks, was taken doing that.

How do you get those

great squeaks? Do you pinch the pick or something?

I call them scroggs. Yeah, you hold the pick very shallow and as you

pick you let your thumb catch afterwards and you get a harmonic, but

you have to be quite accurate where you do it.

I almost had a heart

attack when I read in the liner notes “… Alvin Lee uses

exclusively Scalar.” I thought, “What, he's not using the

(Gibson) 335?” Then I read on and it was the strings they were

talking about, whew!

Scalar are new strings that are made in California. They're very

good. They got a high-density center wire and they get more level

and they last longer.

Do you use like a .046 to

a .010?

No, I use a .048 to .009. I go .009, .011, .015, which is very light

and the .028, .038 and .048. I used to use .052's. Dean Farley, who

makes these Scalar strings, he tried. I rang him up and I did a

digital test recording to find that these strings weren't that loud

and the bass strings weren't as loud as the top strings and he

advised me. He actually sat down and worked out what the best gauges

were for me. I need a very heavy gauge 'cause I do a lot of open E's,

hit the bass strings real hard and if you have very light strings

they go sharp. He did a bit of research for me and came up with the

ideal set. That's why I use Scalar strings exclusively.

In all the time that I've

enjoyed your music a lot has happened in the state of rock 'n' roll.

Well so they say. They keep telling me that.

I was always thankful

that you never veered too far from your original sound.

I explored a way from my roots in 1973-1976. Ten Years After broke

up in '75 and I went through that whole trip of trying to be tasty

and trying to answer the critics who said that I was all flash and

no quality. They would say that I played lots of notes and he's got

no taste and it used to bug me in those days.

Yeah, but they don't know

how to play guitar.

That's true and it was wrong of me to get bugged. My mistake. But I

did let it happen. I went through this phase where I did funky tasty

music, and I did this tour with this band called Alvin Lee and

Company, and I didn't do any of the Ten Years After material. I did

all this tasty stuff. The funny thing was that I got great reviews

from all the critics saying, “Oh, this guy can really play.” But

I missed the rock 'n' roll. I'd get to a kinda place where there was

a rowdy crowd and I'd want to break into something hot and steamy

and the band wasn't quite capable 'cause it was too tasty. I had to

go through that to realize that it wasn't the direction I wanted to

go in. What I realized was that you have to appreciate that what you

do easiest is probably what you do best and that rock 'n' roll and

blues to me is no hard work at all, it's just fun. I can knock out a

rock tune in ten minutes and I kinda think, “If that's so easy, I

ought to do something that's a challenge. I'll try to write Paul

Simon type of songs.”

Yeah, but isn't it a

challenge to write the same A-D-E…?

Yeah, it is. It was a misguided thing and I got away from my roots.

Another thing which told me, seeing the writing on the wall, I went

to see Jerry Lee Lewis, he played in Nottingham, England, and I was

expecting to hear “Great Balls Of Fire” and “Whole Lot of

Shakin” and he did all country tunes. I came out of there feeling

really disappointed. It didn't take me long to realize that if

people came to see me and I didn't do “Goin' Home” or “Good

Morning Little School Girl” they'd be disappointed too. |

I wouldn't.

You wouldn't, then you must be a real fan then. For a little while I

had that band Ten Years Later...

The “Rocket Fuel”

album?

That's right. I wasn't really pinching the name, it was the tenth

anniversary of Ten Years After. I couldn't carry it on 'cause then

it'd have to be Eleven Years Later, etc. But that really was the

coming back to my roots and playing' rock 'n' roll and I've had no

qualms ever since. If you remember like Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck …

all these guys, they changed their styles. They all left their roots

and went into playing softer music - a little bit less energetic.

When I heard your new

record, I said, Good. Man, this isn't the same old songs twenty

years later but a contemporary version of what you would be doing

ten or twenty years later, it's rock 'n' roll!

I was very pleased with the way the album turned out. Terry Manning

stands a lot of credit for that. He kept us playing simple. We have

a tendency to get complicated and start throwing in bars of 5/4

rhythm and maybe trying too hard and Terry would say, “Come boys

this is rock 'n' roll, let's keep it simple.” I think in being

simple, it's probably turned out the nearest a studio album could to

our live sound. We've been trying to do that for years and Terry is

amazing 'cause somewhere in his head, very early on, he seemed to

have a picture … he didn't tell us what to play, he kind of

steered us.

|

|

| He

wasn't a Svengali producer, like some of these producers

that say, “This is my record and you'll do what I say.”

Terry just brought out the best in the band.

What

I wanted out of making the album was, not to be old

fashioned - that could have been the worst thing we could

have done - to sound like we were still stuck in the

sixties. I wanted it to sound fresh but I didn't want it

to sound modern, because I think modern music is kind of

synthesized-computerized and that people are kind of fed

up with that and that's why they're looking back to

established bands for reality in music.

You got bands going out

now miming to tapes on stage and I think it's disgusting

and it's not fooling the audiences. They go to see someone

they like - seeing four or five people on stage and

hearing ten people. Even those that see some guy up there

playing a million notes a minute and they think, “This is

a good guitar player.”

Whereas someone who

plays tasteful like you or Billy Gibbons or. . .

Billy came down to see us in Houston. It was great to see

him again. He's always been one of my favorites. That guy

he can play one note instead of ten and that's more to

where I'm leaning nowadays. But then again it's not even

how many notes. A lot of people think if you're fast

you're good, but you can play real simple lines and easy

notes fast. It's not really how fast you play, it's what

you're actually playing. There's not many people who can

tell.

And not many of them can

get good squeaks!

Ah, me and Billy are the squeak masters.

I like the song, “I'm

Working In A Parking Lot.”

Nobody ever did work in a parking lot (laughs).

|

|

You had a

recording studio a while back, didn't you?

Well, I have one that's moved around a lot. I have one in

my house. I live in Oxfordshire, about forty miles west of

London. Near the airport, easy for touring. I use it

more as workshop, as a song writing tool, it keeps me off

the streets when I'm not doing gigs. Us going to Memphis

was a really good thing to do. The whole environment of

Memphis added something. The blues and jazz and it made

you feel you were somewhere a bit special. I think it rubs

off on the record. It's good to get away from the

telephone. If I'm working at home and have a personal life

that I have to take care of which you don't really need

when you're making a record and you have to concentrate

100% on the recording.

At home, do you

practice or run through scales?

I've never run through scales. I play a lot. I pick up the

guitar and fiddle. I play by instinct, from the hip. I

just pick up and play what seems to come natural and that

seems to work. Which is great 'cause that means I almost

don't have to practice. I have to practice keeping my mind

free of not playing scales but adding those to my

itinerary of licks. Basically, I just hear something in my

head, more a fast reaction, if I hear something I go

through it very quick. The best gigs for me, and the sad

thing is that no one knows, 'cause I can play within the

limits if I'm really cool and professional I'll stay 90%

within the limits don't go wrong…

Play it safe. |

|

Yeah, keeping in

control. And they think, “Great.” they can't compare my best to

my 90%. They think if I don't make any mistakes I'm going great.

When I'm really hot I'm going like 100% and you're liable to make

mistakes. Some people are gonna think, “Hmm, he's not up tonight.

He's making bad notes.” But on a good night I'll hear

something, like a flash of an instinct, and hear something and go

for it and on a good night I'll get it and that's the buzz for me.

That's where I get my kicks 'cause I'll think, “I've never done

that before!” But no one else knows. If I screw it up they'll know!

But I prefer to do that, there's no need to play it safe live.

There's a few tricks, like if you play a wrong note - play it twice

and people will think it's right! (laughs) I've never been studious,

there was always guitars when I was learning, blues. My father used

to like chain-gang work songs - prison work songs - pretty ethnic

stuff for a white kid from England to be listening to but I grew up

with that kind of playing around the house. I tried to emulate the

sounds without copying the notes. If I could make a guitar sound

like John Lee Hooker and by doing it that way I didn't copy the

notes. But some of the best guitarists, they would sit down with

Chet Atkins record - ‘Shit Hopkins’ as we used to call him -

he's like a really good technician - could play anything, and some

guys would sit down and in five or six hours get it perfect note for

note and sound almost as good as those chaps. I didn't really see

the point in that, 'cause I'm only gonna sound almost as good as

Chet and who needs two Chets anyway. And I'm gonna sound almost as

good as those other guys copying it so what I did was try to get the

overall effect that he was getting and using my own notes. Which, I

think is important, that's what I tell young guitarists, don't copy

those solos note for note just try to do your own version of it,

make your guitar sound like the guy but use your own notes and

develop your own style.

You're still using

Marshall.

Yeah, for however many years. Unfortunately I'm not using a Gibson

these days. Sad to say the Japanese are making Toki. They're making

a better '58 Gibson then Gibson. I've been down to Gibson. I showed

'em this Toki and said this is actually your shaped guitar. It looks

just like one and it plays better then theirs, and said why don't

you make one like this? They said, “Oh yeah, we will, we will.”

But they haven't followed it through. The Gibson name is magic and

I'd rather be playing a Gibson, but the Japanese bought up all the

best wood ten years ago. When I took my original ‘58 Gibson

out I had a host of Japanese technicians swarming around it. They

measured the density of the wood, they measured the hardness of the

frets and it came out better. It's amazing. I still got my original

Woodstock Gibson with all the peace signs on it, but it's kind of

getting too valuable to take it out on the road. I don't like

hanging guitars up on the wall, but the Hard Rock Cafe offered me

fifty grand for it and it's worth much more to me. I do take it out

on some gigs, but on this tour I didn't know the crew personally and

so I didn't want to risk losing it.

How would you describe

the difference in eras in rock?

It's like, the different innovators. Django Reinhart was the great

guitarist of the forties and Jimmy Hendrix was the great guitarist

of the sixties. The seventies was a bit hazy. . . and it's all a

matter of taste. There's no "Best" guitarist. The eighties,

there's so many good guitarists, Joe Satriani, Jeff Healy, Stevie

Rey Vaughan, Mark Knoffler, Eddie Van Halen. . .

|

I was really

shocked when I read that Billy Gibbons was his (Van Halen's)

inspiration. . .

Eddie is good, he's a very good guitarist He's not like that guy

Yngwie Malmsteen. Eddie's a hot technician. A bit over the top

really, but even Eddie backs off occasionally!

I like the song, "Going

To Chicago."

Yeah, looking to the roots, that's what that one's all about. The

black masters, the people I used to listen to when I was growing up,

are kind of sadly forgotten, particularly in America. See I was

brought up on American music. I had relatives there that would send

me stuff when it would come out. When I first came to America in

'67-'68, I expected everyone in America would know who Big Bill

Broonzy and John Lee Hooker was. It's American heritage and I was

amazed hardly anybody had heard of these guys. Maybe 20% of them had

heard of B.B. King and not many of them had heard of Freddy King or

Albert King, Buddy Guy and all that. We were going around and

touring and they (the critics) were saying, “. . . this British

blues music you play is great.” And I'm sayin', “It's American

music.” I've been copying American music all my life. So

that song, "Going To Chicago" it's a dedication to those

black guys. You can go down to a blues club there and see the real

thing. Chuck Berry has been so influential to rock ‘n' roll, the

Rolling Stones and Ten Years After and every band I know has at

least one Chuck Berry song on the set. Muddy Waters has always been

a hero of mine. And they're heroes 'cause of their attitude. Someone

was asking me the other day, all the kids these days listen to Eddy

Van Halen or Joe Satriani and they stand in front of the mirror and

practice and so who did you stand in front of the mirror and copy? I

never thought about it, I never stood in front of the mirror.

My heroes were the blues players and you don't stand in front of the

mirror to play blues. You sit down, with a bottle of Scotch and

that's my image of a musician, playing a funky blues club with lots

of cigarette smoke and booze singing the blues. Not wearing

leopard-skin leotards and doing that. Okay, let's get to the meat of

it. You want to ask all about the sex and the drugs and the rock

‘n’ roll! (Laughs)

Okay, so how have things

changed?

There was a big talk about that last night with the band. 'Oh, how

the business has changed so much.' I'm not really into business, to

me it hardly changed at all. People still love rock ‘n’ roll.

Doing live gigs the reaction to me seems the way it's always been.

In fact it seems almost like the same people who haven't grown up.

They still get off on rock ‘n’ roll. It's like "Jungle

Drums", shake it up, the rhythm is gonna get you like the

jungle drums. Just like jungle drums move people, it gets in your

soul, rock ‘n’ roll is the same. Rock ‘n’ roll will never

die! |

Photo by Lorry Doll |

Editor's

Note: Lorry

Doll met some pretty big stars not only through her work with NEON,

but throughout her music career. But the Alvin Lee meeting was the

only time I ever saw her get pre-interview jitters. In the days

before boy bands, a teen-aged Lorry had been a starry-eyed fan of

Ten Years After and in particular Lee. Not only did she have every

album he ever appeared on, but throughout the many years I knew her,

we never missed a single Ten Years After or Alvin Lee tour. So when

the time came to finally meet one of her biggest music heroes, she

was frantic with worry that he would turn out to be a jerk and

destroy her long-time image of him. But Alvin Lee's easy going

manner soon put an end to her fears. Ever the professional, Lorry

tried to keep her feelings to herself and conducted a very

informative interview until the session ended. Then when it

concluded, Lee got a real kick out of the numerous frayed, faded and

well-used albums that Lorry pulled from her bag for his autograph.

-

Jeff Rey |

This

communication grants agreement and authorization to publish the

text and photos of the copyrighted NEON Alvin Lee interview at

www.ten-years-after.com

We'd

like to thank Jeff Rey for his permission to post Lorry's

Interview on the TEN YEARS AFTER Fan Website

|

|