|

John

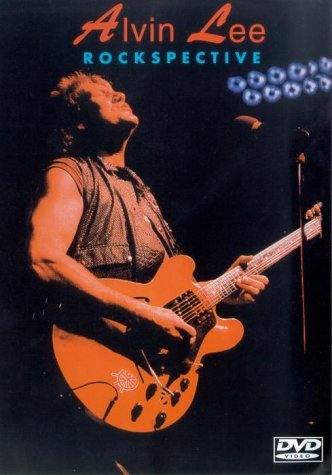

Platt Interview with Alvin Lee - Rockspective 1993

|

JP:

Alvin, anybody who has listened to any of

your music for the last twenty five years or

so would know that your roots are firmly in

the blues, but how did a young boy growing

up in late 1950’s England get to hear the

blues?

AL:

My father used to collect blues, he was an

avid fan of chain/prison work songs,

chain-gang songs, that kind of thing and I

grew up with that, it was always playing

around the house. He was a fanatic, he used

to listen to Big Bill Broonzy and Lonnie

Johnson, more the delta blues and the

Mississippi blues rather than the city blues

and he had a very ethnic collection of stuff

which is as I say, it just must of, sort of

got into my brain at a very early age, and

one day I remember very vividly I was twelve

years old and he went to see Big Bill

Broonzy playing in Nottingham in a club

where I lived and he brought him back to the

house and they went and woke me up so I

could see this guy and I remember sitting on

the floor looking up at this giant man

stomping away playing the blues and I think

that was probably what started it all off,

like the next day I decided to become a

blues player.

JP: Were your first influences

the country blues players that your father

liked?

AL:

Yeah, they were I suppose, it was a mixed

thing, I had previously to that I had played

the clarinet for a year and I didn’t like

it, it was one of those things where they

said we

want you to play an instrument what do you

want to play and I don’t know why I said

the clarinet but I played the clarinet and

then through listening to Benny Goodman I

heard Charlie Christian and I decided I

liked what Charlie was doing much more than

what Benny Goodman was doing, so I

definately had a feeling for the guitar.

It’s difficult to say, all those years ago

but the guitar to me, I think it’s the Big

Bill Broonzy thing that really clinched it,

I just went and swapped my clarinet for a

guitar in fact.

|

|

JP:

Perhaps you could give us an idea of the sort of

thing that Bill was playing that influenced you? JP:

Perhaps you could give us an idea of the sort of

thing that Bill was playing that influenced you?

AL:

Well Big Bill, he used to play his blues, he would

keep the rhythm going and play with his fingers to

give it a great effect (Alvin plays a song that

sounds just like

Don’t Want You Woman on guitar which

shows the Big Bill Broonzy style and the big

influence he had on Alvin)

JP: Well presumably in time you got

to hear and appreciate the city blues players like

I assume like BB King, Buddy Guy ect.

AL:

Yeah, well the next step for me to be honest

was Chuck Berry when I heard Chuck Berry suddenly

I was probably fourteen or fifteen years old and

to me it sounded like the blues with more energy

and the first I heard of Chuck Berry I think Sweet

Little Rock’n Roller probably the first track or

something like that, and it just got to me and I

just loved the energy cause Chuck would play that

kind of…Johnny B. Goode. The truth is I

was interested in the guitar in all its forms. I

listen to classical Andre´s Segovia, I listen to

flamingo stuff and Mel Travis the country guys it

was all good guitar players I mean I was keen to

dabble in all those things.

JP:

Well when you started playing in bands presumably

the R & B and the Blues scene started to take

over.

AL:

Yeah,Yeah well I used to, I mean the first bands I

played with it was pretty much kind of, most of

the gigs were pretty much top forty type you know

and you had to play what was in the charts and in

those days it was pretty grim it was like Frankie

Lane and Pat Boone and stuff like that. We used to

play clubs and maybe do three sets and the last

set we’d go on at one O’clock in the morning

and there’s a half a dozen people there and

we’d play blues and like a couple of people

would come up and say I really liked that ya know,

and that was fun to me, that was more rewarding

than the whole audience all jumping up and down to

me playing some current pop song.

JP:

Presumably by the time you came down to London in

1966 you were pretty much established as a blues

player this was the impression we had of you at

the time.

AL:

Yeah Yeah, that’s right but I did still like

Rock and Roll and I used to play blues with more

energy, in fact there was a lot of purist, it was

quite funny these plot purist blues fanatics and

they would come and they all would wear leather

coats for some reason and all stand around almost

taking notes as you were playing and watching very

intently and they used to come back and say hey,

you’ve played that Elmore James solo wrong and

that really used to annoy me because I said I play

what I feel I’m not copying somebody else and

they’d say

I know but you played it wrong it doesn’t go

like that and so I kicked against all that, so I

use to purposly kind of make it a bit more crazy

and add some energy and try to rock it up a bit,

which is the basis of English Blues to me I mean

it’s American music and I learned it from

Americans and American blues artists added a bit

of energy and kind of took it back, recycled it

and took it back to America and they called it

British Blues which I always thought was very

strange.

JP:

Did you see yourself as part of the big blues

explosion of the late 1960’s I mean there

certainly was a movement but did you see your band

as being part of that?

AL:

Not really, I think when your on the inside of a

band that’s happening your kind of the last to

know, you know, to me it was gig’s and the whole

thing was trying to fill the date sheet and try to

make enough money to eat really, we got more gigs

and it seemed good but I didn’t feel that it was

part of any explosion at the time I don’t know.

JP:

and what about America because you became

phenomenonally successful in America quite quickly

what do you think would account for that?

AL:

Well one of the reasons the second album Undead

was released in America and Bill Graham heard it

and he wrote us a telegram and he said he had this

gig called the Fillmore West and he was shortly to

be opening one called the Fillmore East and he’d

like to book the band at both those gigs, so we

suddenly thought ah we can go to America and I

mean I was American mad you know any thing, I had

American cars, American guitars and anything

American I thought was cool and I just wanted to

get there no matter what.

JP:

Alvin I think your first proper band was probably

the Jaybirds, do you want to tell us something

about them?

AL:

The Jaybirds was a bit later, the first band was

the Jailbreakers. I was thirteen years old and I

did a gig, the first gig that I’d ever done, it

was a cinema in Sandiacre and we played between

the B movie and the main feature like a ten minute

spot, and that was my first introduction to show

business and the Jailbreakers did kind of R &

B stuff and a couple of other little units but

then the original, the start of the Jaybirds was

the Jay Men which then became the Jaycats which

then became the Jaybirds, so a lot of confusion

over what to call ourselves at that time and the

Jaybirds was going pretty strong for about four or five

years and we were quite big in Nottingham and that

made things difficult because we kept moving up to

London and then working in Nottingham cause we

were well known in Nottingham you know, so we

thought we got to go break in London, so we ought

to go down and get a flat and live in London and

then have to travel to Nottingham every Friday to

do the gigs because we got better money there and

we did that three times, moved to London three

times, third time stayed there.

was going pretty strong for about four or five

years and we were quite big in Nottingham and that

made things difficult because we kept moving up to

London and then working in Nottingham cause we

were well known in Nottingham you know, so we

thought we got to go break in London, so we ought

to go down and get a flat and live in London and

then have to travel to Nottingham every Friday to

do the gigs because we got better money there and

we did that three times, moved to London three

times, third time stayed there.

JP:

What sort of stuff were you playing then with

the Jaybirds?

AL:

It was rock’n roll basically R & B, a bit of

blues, we did some Chuck Berry tunes that kind of

thing with the R & B leanings that was the

forerunner of Ten Years After.

JP:

So how did you effect your first big break

then you said you’d come down to London three

times and the last time you stayed?

AL:

Yeah, OK, well it all started around 1966 we

started to get good work in the clubs in London,

we got a residency at the Marquee Friday nights

now that was a big deal in those days because that

was the hot night Friday night and we were there

every week and there were places called Bluesville,

Madhouse, pubs cricketers arms but they were all

pretty good blues clubs ya know, and so we had a

circuit we were working four or five nights a week

in London on the club circuit

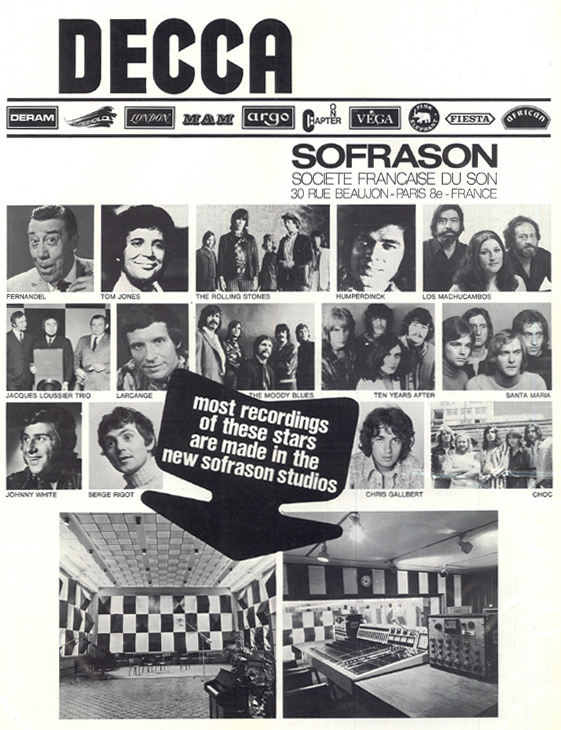

and started to get a name for ourselves as

a live band….and Deram records is a part of

Decca, actually it’s a funny story because

we’d done an audition for Decca records and

there was a producer there, he gave us this song

to play and we went off and worked it out and came

back and played it, and then somebody came down

to the Marquee and said we want to give you

an album deal you know to record an LP which was

very unusual in those days cause you had to record

a single and if that was a hit they’d let you

record an album, and we were I think one of the

first bands to actually start with an album which

I thought was pretty cool, so we actually went

into the studio and started to record this album

and then we got a letter from Decca who signed us

up saying we failed the audition so I don’t know

it was a good clue as to how the music industry is,

the one arm didn’t know what the other was doing,

we were signed on and turned down shortly after by

the same company.

AL:

We did the Ten Years After album first which is

pretty easy to do because it’s your live set

you’ve got your repertoire of your live set and

the numbers you know which work

and you just basically go in and play them

and that’s pretty good, I think it’s by the

time you get to your third album it’s a bit of a

struggle cause then you run out of the songs you

used live and you have to start thinking of new

ones that’s always the crunch.  It’s

funny I remember, I don’t know why it was we

used to play clubs and I remember one particular

time this is the manager of the club came up and

we played the first hour and then we

had two more sets to do and he came up and

said I’m afraid we’ve

had lots of complaints, the audience can’t dance

to you and we don’t want you to play anymore,

and for some strange reason I had so much teenage

confidence that I thought well they’re all wrong

and I’m right

and it’s funny cause it seemed that way

ya know and later on when the blues boom happened

and suddenly that music was accepted I thought oh,

it’s about time now it’s going my way. It’s

funny I remember, I don’t know why it was we

used to play clubs and I remember one particular

time this is the manager of the club came up and

we played the first hour and then we

had two more sets to do and he came up and

said I’m afraid we’ve

had lots of complaints, the audience can’t dance

to you and we don’t want you to play anymore,

and for some strange reason I had so much teenage

confidence that I thought well they’re all wrong

and I’m right

and it’s funny cause it seemed that way

ya know and later on when the blues boom happened

and suddenly that music was accepted I thought oh,

it’s about time now it’s going my way.

JP:

I seem to remember that you also used to

play on what was known at the time as the

underground circuit you did Middle Earth and

places like that, I mean did you, the reason I ask

I wondered whether in fact you liked the fact they

were having bills of bands who played in totally

different styles?

AL:

Yeah I loved that, yeah it thought it was great, I

used to love those things you used to get, to play

a four piece string quartet and then a rock and

roll band and then a poet and I used to think it

was great, it was all very arty and I loved the

underground, I loved being

part of it, cause it was a very exciting

period, it was the period when the whole music

thing changed now up until then the bands had to

wear suits and ties and smile while they sang and

ya, know it was all pretty much a bull-shitty kind

of thing, and the underground was the first time

ya know, you go on in your street clothes you

could play with your eyes closed, just play what

you wanted, incredibly long guitar solos it was

all accepted and to me it was freedom, freedom

from the showbiz kind of thing which I never

really wanted to be part of, but to me it was

natural you know what I mean, it was like you

didn’t have to wear a larmay suit or anything

just go on with a tee-shirt and jeans and play and

that was great, it was truthful and it was free.

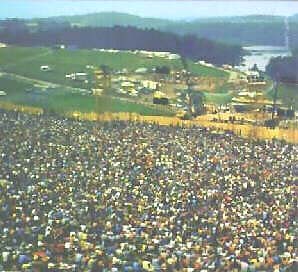

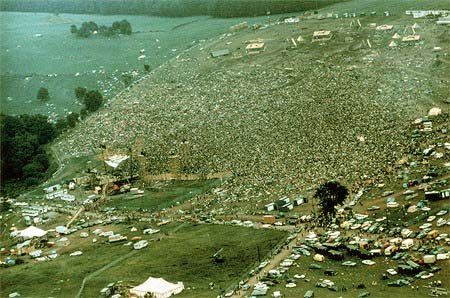

JP: What about Woodstock?

JP: What about Woodstock?

AL:

I was there ya know, a lot of people come up and

say, ya know I was at Woodstock and I’d say so

was I, yeah Woodstock was great, it was an amazing

event but then again nobody knew history was being

made at the time, I knew it was going to be a bit

different when they told us that we couldn’t

drive to the gig and we had get a helicopter that

was amazing…and it was an open sided helicopter

so I put on the old harness and I leaning, hanging

out of the helicopter over a half a million people

and there was a strong smell of marijuana coming

up and it was an amazing start to the day, and

actual memories ya know, it’s all very blurred

purple haze.

JP:

I was thinking also in terms not just of

the gig itself but the film which must have taken

your music to an enormous number of people.

AL:

Yeah, it was the film that in fact made the

difference. We did the festival and then we were

playing like two to three thousand seater Kenettic

Playground type of gigs, Fillmore type of gigs

those things, we did Woodstock, it was an amazing

event, I personally had a good time there but

thought nothing of it and then we carried on for a

year playing two and three thousand seaters then

the movie came out and that’s when it all got

silly and soon we were playing ice hocky arenas

and that kind of thing which actually I didn’t

find all that good, I didn’t like playing those

places, we were playing to security guards with

cotton wool in their ear and a big orchestra pit

with barriers and ya know it seemed to me that no

one was listening. I perfer the underground phase

ya know, like the Fillmore type gigs they were

more clubby and I prefer a clubby vibe you can,

sweat dripping down the walls and the sound

pounding on the walls and that’s some of the

best gigs that I’ve ever done.

JP:

Alvin you said that the whole move to stadium

rock was one of the reasons that you decided

ultimately to break the band up.

AL:

Yeah it was the whole band got disenchanted,

it was that feeling of what are we doing here, no

one is listening, ya know a lot of people say

Woodstock made Ten Years After but in fact it was

the beginning of the end when the movie came out

there was a lot of disenchantment, I didn’t like

being a rock and roll star in inverted corners, I

thought of myself as a musician. I was very naive

in those days ya know, I thought I’ve already

made much more money than I should do anyway and

that wasn’t kind of part of the plan and I tried

to hold it all back in fact I did what I called

deescalated the whole thing and stopped doing all

the interviews and all that and didn’t really

want to play that game at all which seemed to even

make it

worse, then they thought I was Greta Garbo.

No, it’s funny the success that everybody

thought it really must be great when you made it

but that wasn’t that good at all, I prefer the

earlier parts.

JP:

But you still kept on going to the states I

believe you did something like twenty eight tours

in five years or something which is a phenomenal

amount of work to get through.

AL:

Yeah well the band was over toured, I remember

complaining about that because we would do like a

thirteen week tour of America, come back to

London, have two days off and then start on a ten

week tour of Europe, and then some bright spot

would call me up on the telephone and say your in

the studio next week we hope you’ve got the

songs ready, and I was writing songs in the taxi

on the way to the session and things like that and

I was just getting too much pressure and I needed

time off, and there was an album called A Space in

Time which was a dedication to that time off that

I managed to dig my heals into the ground and say

that’s it, I’m not working, I want to write

songs, I want to be a musician, but they kept

saying but Alvin you can make millions of dollars,

there was a demand for the music but I didn’t

feel that I was living up to it. I didn’t feel I

was getting enough creative time to supply good

music, cause you had to rush it all and I was over

toured. It’s funny because when you start a band

off you just want to fill your date sheet up

that’s your ambition to work six nights a week,

when that happens you go four five or six years

maybe just doing that and being glad of it but

suddenly or sooner or later you think where are we

going from here, I used to say we’re turning

into a travelling juke-box, it sometimes used to

feel that way ya know, you’d arrive at a gig,

then plug in and play and take it out and off to

the next town same thing, and you do that like

fifty or sixty times in a row and you start to

loose the spontaneity.

JP:

So was your first solo album which I think was the

one with Mylon Le Fèvre a deliberate attempt to

get away from the old band sound?

AL:

Yeah,Yeah it was it more of a country kind

of feel more of a melodic kind of thing, more

tunes and less and it wasn’t rock and roll, I

mean I was getting away from that rock and roll

kind of tag of course, I was probably a bit too

aware at the time of criticism and press people

who use to call me Captian Speed Fingers and All

Haste and No Taste and things like that, yeah I

was turning against the whole rock and roll thing

for awhile, in fact there was a period where I

didn’t play any rock and roll just to get away

from that image---it was a personal problem, I had

it all wrong to be honest, ya know I say I was

very naive, but I was trying to keep my

credibility and that has always been the important

thing to me, I think if you loose that then your

in trouble and if I started to feel that I was a

rip off and I wasn’t being truthful to myself

then I couldn’t really play thinking that you

have to have your own credibility to continue

it’s very important.

In fact there was a band, I did an album

called In Flight and it was called Alvin Lee and

Company. It was an eight piece band, a percussion

player, two girl singers, Mel Collins on sax, and

it was quite a funky little outfit actually and I

enjoyed playing that and I got totally away from

rock and roll and I didn’t do all the classic

songs, I didn’t do any Ten Years After songs and

that was the rebel again ya see, it’s a funny

thing how you turn against what makes you famous,

I know Jimi Hendrix he hated to play Hey Joe which

I thought is a great number I still play Hey Joe

he hated it because it was so popular and I for

awhile I felt like that about I’m Going Home,

it’s like it’s the only thing we played

everyone would shout I’m Going Home all the way

through the set it gets kind of annoying, so I did

this whole set played for about a year never

played any of those tunes but one day I went to

see Jerry Lee Lewis, he was playing in Birmmingham

England. I’ve always been a big fan of Jerry Lee

and he was playing Country and Western, he was

going through a funny phase and he didn’t

play Whole Lotta Shake’n and Great Balls

of Fire and I came out of that gig greatly

disappointed and realized that if people came to

see me and I didn’t play I’m Going Home or

Love Like A Man they’d feel the exact way that I

felt and I didn’t want my audience to feeling

like that when they left the gig, so the very next

day I went back to the band and said I’m doing

I’m Going Home tonight and played it and it felt

great, it was like finding an old friend after a

few years ya know.

JP:

Alvin now you’ve got a great new album out,

AL:

Thank You Very Much,

JP:

and to me despite the fact that it still has the

blues feeling you know, the rock and roll feeling,

it sounds pretty modern to me particulary on a

track like “Real Life Blues” tell me something

about the track and how it came about.

AL:

Real Life Blues ok, well it’s a real life

feeling I was working in the studio until about

two in the morning and I decided I needed a little

break just to lighten my head a bit so I went in

the house and switched on the TV and just caught

the war breaking out in Yugoslavia, a highjacking

and several murders and I thought and it really

effected, I was trying to be creative and it I

thought so much trouble in the world it’s time

we had some better news maybe a song in there so I

wrote the song basically on that feeling came back

into the studio. It was a bring down to me and I

was angry and the song is kind of a mellow chord,

I didn’t play any lead at first I had the song,

and then I did a lead guitar it was really angry,

I was angry at the world ya know and so much

trouble in the world, I was doing all this really

manic guitar.

I

then called up George Harrison, he’s always been

a mate of mine and he’s played on a lot of my

albums and I’ve played on his and I said any chance that you come play a bit of slide on this tune, it

needs a bit of slide and he said I’ll be right

over and he came over and he played.

I

took my guitar out of the mix ok so he just had

the basic chord feel of it and he played this

beauitful sympathetic slide guitar that was so

wonderful and it turned the whole song around for

me cause instead of so much trouble in the world

it was like so much trouble in the world and he

did the guitar fills and the first solo and I was

going to play the second solo so I checked out

what I was playing by the end of the track it was

crazyness ya know, it didn’t fit at all so I had

to rethink the whole end of the solo and make it

more kind of mellow and sympathetic and that’s

what he did to it, he took the angry bit out of it

and he turned it around and made it much more

interesting for me, it’s nice when that happens.

JP:

There’s a real variety of songs on the album

everything from R & B Rock and Roll and a

certain amount of

blues, something like Jenny Jenny which is

superficially sounds like a Chuck Berry riff

but there’s all kinds of 1950’s things

going on in there as well.

AL:

Yeah that’s right, I was very happy with that,

that was one of the songs it took me about ten

minutes to write that one, in fact I was working

with my song writing collegue Steve Gould and

we’d been working all day on this song and

getting nowhere and I said to hell with this,

let’s play some rock and roll and we wrote Jenny

Jenny in ten minutes and I was very happy with it

because to me it sounds like it was a song

that should have been written in 1958 and

escaped that’s basically it

and to me I thought it was Jerry Lee Lewis

cause the guitar is Chuck Berry (the guitar fills

are Chuck Berry) but the rhythm is Jerry Lee

Lewis.

JP:

To some listeners who maybe haven’t heard your

music in some time there is a superficial

difference between I’m Going Home and the stuff

on the new album, but do you really see it as that

different?

AL:

I don’t, I see Jenny Jenny and Going Home to me

are very very similar, it’s just cooking rock and roll twelve bars they

have different flavors but to me it’s all the

same roots that’s rock and roll it’s Jerry Lee

Lewis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry and what you

can do with that whole feeling.

JP:

How do you think—I mean people still regard you

as a guitar player as well as everything else and

very much a solo guitar player, I mean do you

think your solo playing has changed much over the

years?

AL:

Some ya some, I’d like to think its got better

I’ve got more control I think now,

I’m probably appreciating spaces more I

think sometimes if you—a gap between the notes

is sometimes more important then putting notes in,

ya know it’s like light and shade and everything

else.

JP:

In thirty, forty, fifty, sixty or whatever how

many years time it is and that great bluesman in

the sky calls you to play that last lick how would

you like to be remembered?

AL: I’d like to be remembered as a musician

rather than—I’ve always tried to be a musician

rather than a pop star, I hate anything to do with

pop music and I don’t really like show business

as I’ve said my heros are people like John Lee

Hooker and Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker is

over eighty now and still playing and I think

that’s great, if I ever make it to eighty I hope

I’m still playing too, in fact I’m sure I will

be because I don’t want to stop now, and it’s

too late for me to get a proper job.

|

|

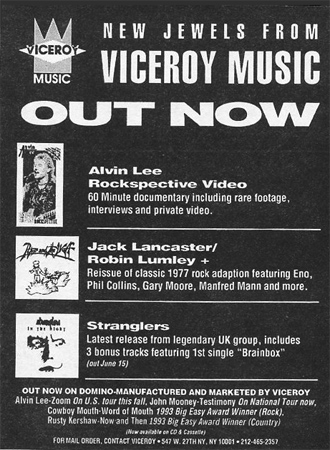

Alvin

talks about his new release called

ZOOM:

Q:

Alvin how did you come up with Zoom

for the album title?

AL:

Well Zoom seemed to get the best reaction

from people.

Q:

Can you tell us about the songs on

this record?

AL:

The songs have been written over the past

two years or so, I write songs all the time,

it’s my hobby and my trade as well. It’s

a pretty good collection of songs and I’m

really happy with “Real Life Blues”

“Jenny Jenny” and “Remember Me” (when

I’m dead and gone) which is actually about

my own epitaph. I’m looking forward to

people hearing “Jenny Jenny” it’s like

a fifties rock and roll song that sounds

like it sould have been written over twenty

years ago, and Clarence Clemons (from Bruce

Springsteen’s E Street Band) is on it too.

I was thinking yesterday that my

favorite song was “Use That Power” which

to me has a double meaning. It’s all about

ecology, protecting the environment and

about being pissed off about dumping all

that shit into our environment, so Use That

Power is a warning cry to stop it now.

It also means Use That Power as in use your

power and change things back to the way it

ought to be, and use all your power.

Q:

Alvin, are all the compositions on Zoom your

originals?

AL:

Yes, although I co-wrote some of them with a

man named Robbie Sideman who is an American

living in LA, he came over to England and we

wrote “Anything For You” as a middle of

the road song on this collection, but it’s

still in the good old rock and roll style.

It’s a good jamming blues song and Jon

Lord (from Deep Purple) plays the Hammond

organ and Clarence is on sax.

Q:

Describe if you would the style of

music that you consider Zoom to be under.

AL:

It’s a blues-based-rock and roll thing I

suppose, if you needed to pigeon hole the

thing, it’s basically blues, with the

roots of rock and roll with some progressive

leanings. I’ve always thought of myself as

a progressive musician, I did my gig when I

was around thirteen or so in Hamburg,Germany

and it was the first time I was ever out of

England.

Q:

Who have been your most important

influences in music?

AL:

Well to begin with I was brought up

listening to all kinds of blues, as my

father had a huge collection of blues

records and I moved towards the most ethnic

kind of blues, people such as Muddy Waters,

John Lee Hooker and Lonnie Johnson were the

original artists that I picked up on.

As

I was growing up, Big Bill came to visit my

house, my parents went to one of his shows

in Nottingham and brought him home with

them. I think I was twelve at the time and

the whole thing had a big impact on me. Bill

sat in our living room and played his guitar,

after that I discovered Chuck Berry, rock

and roll, Jerry Lee Lewis and all the rest

of them. I still listen to Jazz guitar, Wes

Montgomery, Barney Kessel and George

Benson, it’s thanks to my parents that I

was exposed to quite a lot of different

music and I feel the thirties swing stuff

had a big influence on the history of rock

and roll as we know it today.

Q:

When did you decide to take these

influences and venture out on your own?

AL:

I think in 1962, was the start, as

there was a blues boom headed by John Mayall

and suddenly the blues became the “IN

thing”.

I always loved to play the blues

before it became popular but before it was

accepted. We used to get tossed out of clubs

because people complained that they

couldn’t dance to our music, so I went

back to basic rock and roll.

When the blues boom came I already knew all

of the great songs because I’d been

exposed to them all my life, so suddenly I

found myself back in the blues.

It all goes in cycles, I went through years

where I’m very blues based, then I move to

rock and roll then into a psychedelic period

and then onto progressive, and then back

into the blues, and around it goes.

My first time in America back in 1967 I was

amazed to discover that most Americans

didn’t know who Big Bill Broonzy or Lonnie

Johnson were. After all this is your music

your heritage all we did was copy it, so in

fact I was playing American music with some

English energy added to it and then

recycling it and sending it back to America,

I’ve always been a fan of American music.

Q:

Alvin, how did you get George

Harrison, Jon Lord and Clarence Clemons to

help you on Zoom?

AL:

Well, I’ve known George since 1973

when Mylon LeFevre and I were working on the

On the Road to Freedom recording which for

me was a positive step away from rock and

roll.

George wrote a song on that album called

“So Sad (no love of his own) and ever

since that time he likes to come over with a

guitar in hand and a bottleneck, he plays a

very good slide guitar by the way.

Jon Lord I’ve known since the 1960’s,

he’s played on some of my albums and

I’ve played on his. George, Jon and I all

live very close to each other in the part of

England called The Thames Valley.

Clarence I met on the Peter Maffay tour

recently in Germany and Clarence and I get

along just great, we shared a dressing room,

sat around and just jammed, Clarence said

I’ll be on your album if you’ll do the

same for me. Clarence is great I love him

and he’s certainly a “larger than life

human being”.

Q:

Alvin,who else do you have in your

band right now?

AL:

Alan Young is with us as drummer and

has been for the last three years and as his

name implies he’s the young-blood in the

band.

Our bass player on live gigs is Steve Gould

and he and I wrote Jenny Jenny together. On

this album though I used Steve Grant. We all

have a good relationship and we’re going

to keep working on it.

Q:

Alvin, what do you think of the new

generation of blues guitar artist coming

along now, like Gary Moore for instance?

AL:

Yeah well, I think it’s great and I

know Gary pretty well, he was very surprised

that his album did so well, because the

record company made it very clear that they

didn’t want blues they wanted heavy metal.

Gary had gotten away from his heavy metal

image and now all the record labels want the

blues.

Gary plays city blues and not the country

blues, which is in the more acoustic style,

like the Mississippi Delta Blues. There are

so many forms and variations of the blues

that hopefully this craze will embrace all

of them.

Q:

Do you think Gary may be using some

of the work that you yourself pioneered as a

member of Ten Years After?

AL:

Yes, well I might have pioneered

something with Ten Years After, just as BB

King did it before me. It’s just

influences and Gary told me that I was his

biggest influence after seeing a Ten Years

After gig. He never forgot it because he

fell off his motorbike on his way home from

the concert.

It’s good to be an influence like that,

I’ve met a lot of guitarists on the road

who want to play my guitar, they show me

their version of the intro to “I’m Going

Home” and they play it exactly the same

way that I did, note for note, even I

don’t do that, I change it a little bit,

so I say to them that’s very good now go

off and learn your own licks.

Bruce

Q:

Would I be close in saying that Zoom

highlights each part of your music career?

AL:

All the styles that I play, blues, rock and

roll progressive or even psychedelic are all

in evidence on this record, it sounds like

me but it also pays tribute to the roots too.

Q:

Then are you happy with the overall

results on Zoom?

AL:

Yes I’m happy as a sandman, I just

heard it last night for the first time and

it sounded great, it’s the first time

because for the last three months I’ve

been working on it everyday and I think

it’s my favorite album so far.

|

|

|

Gibson Musical

Instruments decided to open their United

Kingdom office with a party to launch

the opening of a U.K. office, plus the

debut addition of a limited run of a

“Scotty Moore” signature issue guitar.

The publicist for the event had used

many resources in which to invite every

guitarist in Europe to attend this

spectacular event. The invitation also

included a rare chance to perform with

Scotty himself.

After a very long day of

press and travelling around London, we

finally arrived at "Air Studios” and were

promptly rushed on for more camera shots and

a sound check. The same band was there

who had joined us on the spring U.K. tour.

Scotty and D.J. Fontana

were on stage for rehearsal, while the

publicist introduced us to some guest who

would meet Scotty later on, and perform an

informal jam. While over in the corner of

the studio stood Jack Bruce, Alvin Lee and

Gary Moore. I already knew Alvin from our

visit with George Harrison and Jack was

invited through the Rolling Stones London

office. While over in the corner of

the studio stood Jack Bruce, Alvin Lee and

Gary Moore. I already knew Alvin from our

visit with George Harrison and Jack was

invited through the Rolling Stones London

office.

Gary Moore was the real

surprise guest here, he’s one of the best

white blues guitarist in the world these

days. Upon meeting him, he was very humble

and said he would play on anything Scotty

would have him. Gary played an amazing solo

on “One Night With You” and “Hound Dog” with

Jack Bruce playing bass and doing the

vocals.

A roomful of hero’s from the 1960’s and

1970’s. Gary told a wonderful story

recounting his very first guitar, which was

a small plastic Elvis model that his parents

had bought for him in a Belfast, Ireland

five and dime store. I could tell that Gary

loved music and playing the guitar more than

anything else in his life, because it was

his life.

Alvin Lee, Gary Moore, Jack Bruce

|

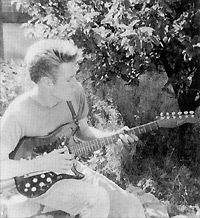

Jimmy Page said of Alvin Lee, “he’s just great”

said the most unimpressionable Jimmy, as his

eyes were spellbound from watching Lee’s

fingers!

When

someone asked Alvin about being the fastest

guitarist in the world his firm reply was:

"I don't think so, no way. There are

plenty of guitarists faster than me.

Django

Reinhardt was faster than me and he only had

two working fingers. It's a silly title

anyway. I never was, I never will be and

who's counting anyway?"Alvin Lee in

1984

|

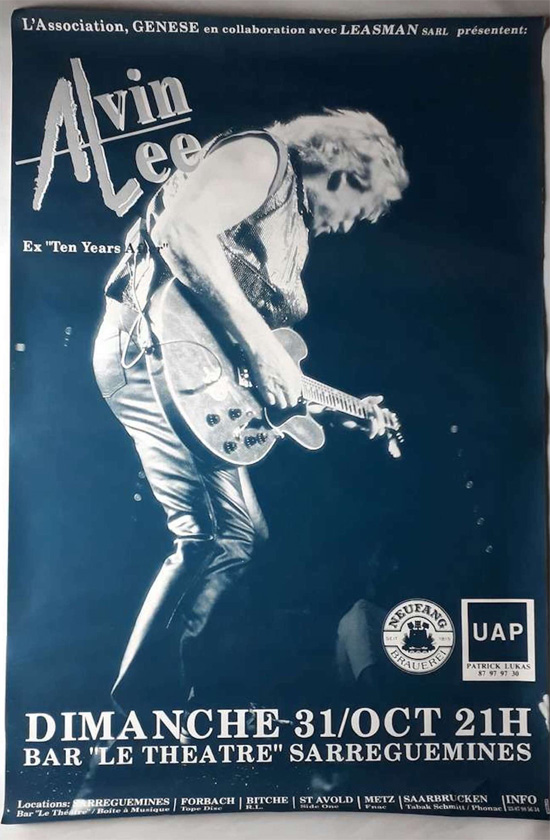

31 October 1993 -

Théatre in Sarreguemines, France

|

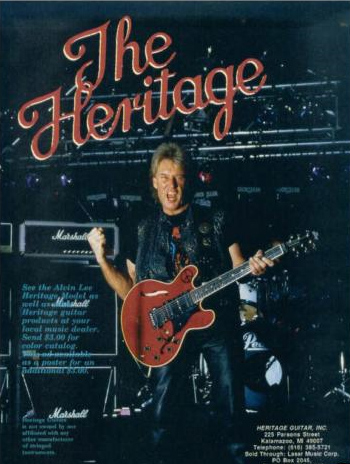

The Heritage ALVIN LEE

MODEL was the ES-335 style semi-hollow bodied

signature model of Alvin Lee and is based on

Lee's iconic <Big Red> 1958 Gibson ES-335.

The Heritage Alvin Lee

Model was made from 1993 to 1996 and had a

cream bound solid curly maple top and back

with solid curly maple sides. The set neck was

one piece mahogany, cream bound with a 24.75"

scale length and ebony fingerboard with dot

inlays. This guitar had two humbucking pickups

plus a single coil in the middle position

(Alvin Lee modded his original ES-335 by

adding a stratocaster single coil pickup in

the middle position). Hardware was chrome

plated and the transparent cherry finished

body was 16 inches wide and 1.5 inches thick.

|

|

SHORT

TAKES

– AS YEARS GO BY – DECCA RECORDS

From

1993

Mark Paytress Remembers The Days When

Decca Was The Nerve Centre Of

British

Pop:

As Years Go By, the 1960’s revolution

at British Decca.

David

Wedgbury and JohnTracy

They

gave away the Beatles, and even let eager

young starlets like David Bowie, Marc Bolan,

Joe Cocker, David Essex, Olivia Newton John

and Rod Stewart through their grasp. But to

every Rolling Stones fan, Decca remains the

quintessential 1960’s label.

You

knew its offices were crammed with

stuffed-shirt executives who had their hands

forced into doing business with acne-riddled

suburban lads on the make; but that didn’t

matter. It was obvious that Tom Jones and

Engelbert Humperdink were its golden boys,

but the urgency and glamour of the Stones,

Marianne Faithfull and their confrontational

manager Andrew Oldham provided Decca with a

large helping of

1960’s (Zeitgeist) that no amount

of myth, destruction can shake off.

Then

one morning the 1960’s were over, and so

too were Decca’s glory days: the Rolling

Stones had quit, Tom Jones packed his bags

for Las Vegas, the label invested unwisely

in progressive rock, and the emerging glam

rock craze was missed completely.

All

Decca had left was a past, which it began to

recycle rather shamefully during the

1970’s.

Thus

annoying the Stones to such an extent that

the band had placed full-page ad’s

requesting consumers not to buy the

label’s repackages. This rapid fall from

grace – which eventually led to a takeover

by Polygram Records, in the early 1980’s

wasn’t good news for it’s shareholders;

but it did reinforce the notion that the

company was as inextricably entwined with

the 1960’s as “Twiggy” and “I’m

Backing Britain” campaigns.

Nostalgia

for that decade, which has continued apace

since around 1980, has ensured

that via the subsidiary Deram imprint,

the back-catalogue has been polished up for

the contemporary CD consumption. This has

largely been through the efforts of John

Tracy, who is a gentle giant of a man whose

knowledge and attention

to detail has resulted

in a remarkably well-conceived stream

of archive reissues. Bonus Tracks, enriching

sleeve notes, and fine sound, not to

mention the “Special Price”

stickers, has ensured that the Decca

catalogue remains a highly attractive

proposition.

And

now, to confirm the label’s prime position

at the expense of 1960’s pop culture comes

the latest project, a book CD tie-in titled,

not unexpectedly, “As Years Go By”. The

music provides an interesting résumé of

Decca’s hits (Billy Fury, The Small Faces)

and misses

(Marc Bolin and David Bowie), while

the accompanying book (published by Pavilion

Press) brings the era alive

in gloomy, monochromatic glory, via

the distinguished photography of Decca

staffer David Wedgbury.

Wedgbury

spent the entire decade at Decca, shooting

hundreds of record sleeves, publicty photos

and advertising material. And his

magnificent pictures have a vaguely

classical quality about them, artfully

composed, but rarely ostentatious. “Being

the staff photographer, you ended up doing

everything that was wanted,” he recalls,

“including going round the dining-table

photographing Mick Jagger Jagger eating with

Sir Edward Lewis, and catching them signing

the contract afterwards. Actually, I

didn’t really enjoy that kind of social

photography very much at all”.

What

Wedgbury revelled in was welcoming artists

into Decca’s design studio at Black Prince

Road, Lambeth, and spending a couple of

hours with them on a shoot. Despite being an

in-house photographer, he maintains that he

had a free hand, and was keen to put his

considerable training to good use. “I

pursed a very poised, serious approach to

photography. I really wanted to get away

from the cheesy, Clif Richard – type shots,

holding a guitar and smiling for the camera,

and treat the whole thing in a much more

profound way”.

Inevitably,

minor servings of “Cheese” find their

way into anyone’s portfolio – witness

the toffee-apple-chewing Applejacks outside

a confectionist’s or a decidedly bland

(and youthful) Olivia Newton John at the

outset of her career. But with the right

subject, Wedgbury’s acute ability to

capture an artists essence comes into its

own.

One

of the most dramatic pictures captures a

quietly confident Marianne Faithfull, at the

outset of her career, when she still played

the knowing virgin. “She was very intense

when she posed for the camera, “recalls

the photographer, who took the session at

the singer’s new London flat. “She gave

the impression that she was trying to seduce

you, pull you through the camera lens. She

basically struck those poses herself; she

was very much a natural, very easy to

photograph”.

On

the other hand, a real trickier subject was

Roy Orbison, who looked very strange without

his dark sunglasses and provided numerous

“Glare” problems when he wore them.

“That was taken in a corridor at

Television Centre on the way to the set of

“Top Of The Pops” “says Wedgbury. “I

was particularly struck with the

personalised guitar strap and thought I’d

make something of that”. The results

provide a fine variant of the smiling –

with guitar pose.

Not

every subject he worked with had a natural

charisma, though, and a quick glance through

“As Years Go By” provides an amusing

resume of many of Decca’s less than

alluring investments. Collectable recording

artists the Beat-Stalkers may be, but their

line in flared tartan strides and demeanour

that brings new meaning to the word clueless

will ensure them a place in rock ´n´ rolls

vast amusement arcade. Likewise the band

called “Timebox”, a mostly quintet who,

judging by the photo here, certainly put the

freak into freak-beat. Whatever happened to

the guy who struck the near-perfect “I Am

Not Here” Warhol Pose?

Wedgbury

identifies three categories of subject

during his years as a pop photographer:

those who could be photographed with little

prompting; those who required considerable

manipulation; and those who, whatever you

did, were entirely useless. The photographer

remembers two young mid 1960’s would be

stars, Marc Bolin and David Bowie falling

into the first category. Every frame of

every film I took of them was printable and

useable”.

He

insists. Wedgbury took both to outdoor

locations: “I strolled around the Inns Of

Court with David Bowie,” he recalls. “It

was autumn and the leaves were falling.

There was quite an interesting light , it

was a bright autumn day, and he did

everything I wanted him to do. But to be

honest, I can’t remember much in terms of

conversation.

“The

Bolan session was done in Holborn. I bought

him lunch afterwards, and while he was

eating, he really opened up. He had it all

sussed, he was really going to be big and

make a lot of money”. But did it sound

convincing? “No, he was just a teenager

and I was already in my early 20’s. I

dismissed him as a young kid”.

Decca

may have had little success with the likes

of Bowie and Bolan: but the fact that so

many future stars were at one time linked to

the label confirms its status at the heart

of the 1960’s pop culture, if not its

artistic development skills. And that’s

what the book’s subtitle,

“The

1960’s Revolution At British Decca”

reflects, rather than any counter-culture

demand for the impossible. Though, somewhat

incongruously, the label did have the

era’s leading mischief-makers – The

Rolling Stones – under its wing. The

Rolling Stones, under the tutelage of Andrew

Oldham, were at loggerheads with their

pay-masters for much of their seven years at

Decca. They determined where they’d record,

and broke with the mould by recruiting their

own photographers for their record sleeves.

Nevertheless, Wedgbury photographed them

throughout the decade, for press shots like

the “Beggars Banquet” party and for

their Christmas cards. And, he says, they

were truculent from the start: “For the

very first session, I had the band booked

into the studio. Two of them, Charlie Watts

and Bill Wyman turned up on time. Mick

Jagger telephoned twenty minutes later to

say that he wouldn’t be able to make it,

and the other two didn’t even turn up at

all. That really set the tone. “I can

remember several occasions

when the Stones came to lunch with

Sir Edward Lewis – (Decca’s bigger than

life chairman). One time, they arrived in a

wide assortment of clothing, and Mick Jagger

wore a French-style, horizontally striped

T-shirt that was loose on the shoulder. Sir

Edward and the suits were horrified. The

Stones had this belligerent attitude and

treated everybody in a fairly disdainful

way. That’s what really set them apart”.

The

Rolling Stones, revolutionary gestures were

a far cry from the reality of the Decca

set-up, though. “Sir Edward Lewis was an

accountant who made his pile of money before

the war”. Remembers Wedgbury, “and the

Albert Embankment head office was run in a

very disciplined way, rather like a spoof of

the Civil Service. He had a lift for

personal use, and there was a whole series

of dinning arrangements, the chairman’s

dinning- room was complete with heavy wood

and silver service, the executives

dinning-room , and the workers dining-room

where you could queue up at the counter or

pay an extra 6d and have waitress service”.

Despite

the “Stones” towering presence at Decca,

the group that best captured the mood of the

decade, according to Wedgbury, was The Who.

“They had a tremendous presence, they were

innovative in that they into Union Jacks and

visually exciting clothing, and they were

co-operative!”

“The band only had a short spell with

Decca – (via its Brunswick subsidiary),

but

after one particularly successful session,

their manager Kit Lambert employed the

photographer on a freelance basis. “I used

to arrive at their Sloane Square office, and

from there, we’d travel in a black

limousine to their concerts. It was the time

when they were smashing their instruments

and the idea was that I’d go out with them

and publicise that activity. I worked with

them right up to the “My Generation”

album cover, which we shot in Docklands.

When I hear “My Generation” even now, it

still makes the hairs rise on my neck”.

Thanks to: David Wedgbury, John Tracy and Hannah

Griffiths at Pavilion.

|

|

|