|

|

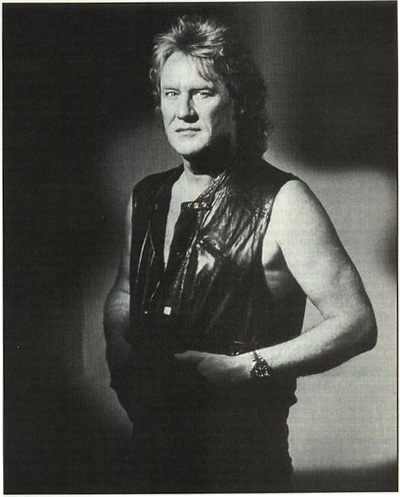

| April 18, 1994 - Alvin Lee filmed live on

stage for the "Ohne Filter Extra" Show on German TV

Track list: Keep On Rockin', Long Legs, I Hear You Knockin', Good Morning Little Schoolgirl, Slow Blues In C, I Don't Give A Damn, Johnny B. Goode, I'm Going Home, Choo Choo Mama, Rip It Up.

It also features a five minute interview with Alvin Lee

|

|

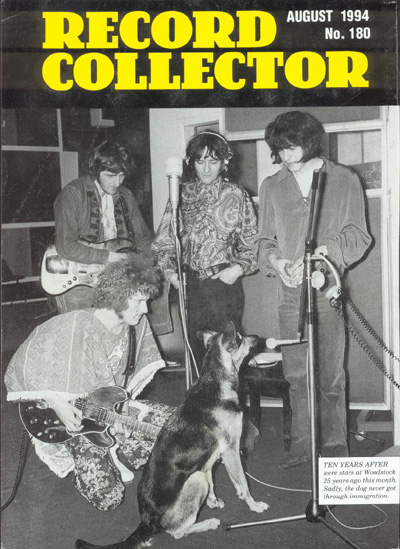

Is

There Life After Rock Guitar Godhead ?

Article

by – Roy Trakin – For Musician Magazine 1994

Alvin

Lee had reached the pinnacle of rock guitardom. Of

course, by the time Woodstock was over, his “I’m

Going Home … by helicopter” histrionics would have

been over shadowed by Jimi Hendrix’s climatic “Star

Spangled Banner,” but for that moment, all flying

sweat and flashing fingers, the twenty four year old

Nottingham lad emblazoned himself on the national

consciousness, thanks, in large part, to the subsequent

movie of the event.

Overnight, Ten Years After burst onto the American

rock scene, turning its fiery focal point into a full

– fledged rock star, and making him absolutely

miserable in the process.

|

|

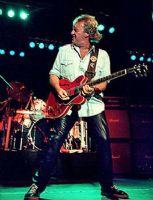

The Cubby Bear Lounge – Alvin Lee –

September 22, 1994

Address – 1059

West Addison Street Chicago, Illinois

“I saw Alvin Lee

at the Cubby Bear Lounge, across from Wrigley Field, a few

years back.

He was the band,

so anything less, is well …less. When I saw them, I think

it was their farewell tour. Apparently, the “Space In

Time” album didn’t fit well with the flying fingers

approach Alvin Lee had with previous Ten Years After

L.P.’s and the fans reacted negatively.

It was all good to

me and still is…Keep on Rocking”.

Alvin Lee at

Club Bene in New Jersey 1994. This is a venue where a

lot of yester-year guitar greats come to play.

|

|

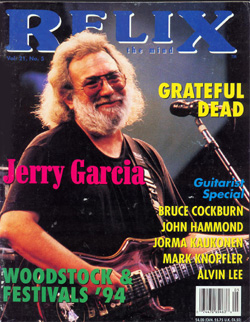

RELIX -

Vol. 21 No. 5

Alvin Lee 30 Years

Later:

By John McDermott

“I love what I’m

doing,” boast Alvin Lee about his musical career, now in

its third successful decade. His satisfied joy can be

heard throughout “I Hear You Rockin´,” the fabled

guitarist’s newest recording from Viceroy Records. Lee’s

career started with early encouragement from his

music-loving family. Born in England’s historic village of

Nottingham in December 1944, Lee’s parents, fans of

diverse pioneers such as Segovia, Leadbelly and Charlie

Christian, supported his early embrace of the guitar. The

direction of his career was steered by a dramatic visit

from one of his idols. “My real love at that time was

Delta country blues,” remembers Lee. “Big Bill Broonzy was

someone I truly admired. I actually met him when I was 12

years old. My parents had gone to one of his gigs and

invited him back to our house afterwards. He was playing

guitar in our front room, and I was sitting on the floor

looking up at him. He so inspired me that day, that I

decided then to become a blues musician like him.” “I love what I’m

doing,” boast Alvin Lee about his musical career, now in

its third successful decade. His satisfied joy can be

heard throughout “I Hear You Rockin´,” the fabled

guitarist’s newest recording from Viceroy Records. Lee’s

career started with early encouragement from his

music-loving family. Born in England’s historic village of

Nottingham in December 1944, Lee’s parents, fans of

diverse pioneers such as Segovia, Leadbelly and Charlie

Christian, supported his early embrace of the guitar. The

direction of his career was steered by a dramatic visit

from one of his idols. “My real love at that time was

Delta country blues,” remembers Lee. “Big Bill Broonzy was

someone I truly admired. I actually met him when I was 12

years old. My parents had gone to one of his gigs and

invited him back to our house afterwards. He was playing

guitar in our front room, and I was sitting on the floor

looking up at him. He so inspired me that day, that I

decided then to become a blues musician like him.”

In addition to

Broonzy’s passionate folk blues, Lee was thrilled by the

exotic electric sounds of another American, Chuck Berry.

“He sounded like the blues with more energy,” said Lee.

Eager to showcase

his own hybrid of blues, rockabilly and rock and roll, the

young guitarist still only 13, formed the “Jailbreakers,”

his first band. Two years later, Lee along with fellow

Nottingham teenager Leo Lyons, formed “The Jaybirds.” By

1964, the Jaybirds had earned considerable notice among

Britain’s burgeoning blues cult via its energetic stage

shows and billing as “Britain’s Largest Sounding Trio.”

Seasoned by many small gigs throughout the country, Lee

and Lyons relocated to London. Lee ability as a soloist,

stood out in that crowed field, which included Mick

Taylor, Peter Green and Paul Kossoff. Eger to measure

their efforts against established blues outfits, like

those headed by Alexis Korner and John Mayall, Lee and

Lyons established Ten Years After, whom they recruited

drummer Ric Lee and keyboardist Chick Churchill for. The

group’s early club appearances had an immediate impact, as

Lee’s fluid dexterity and slashing solos helped to enhance

the group’s momentum.

With the blues

movement in full bloom, the group secured a contract with

Deram, a subsidiary of London Records. “Ten Years After”,

the band’s impressive debut disc, whisked them off to a

rousing start. Lee’s fast advancing reputation and a

coveted Friday residency at London’s Marquee Club,

afforded Ten Years After a critical advantage in an

increasingly competitive field. “Undead”, its second

release, provided them with a U.K. chart break-through,

reaching number two in September 1968. Recorded at Klooks

Kleek, the London nightspot where John Mayall had recorded

his debut disc, the superb “Undead” showcased the group’s

impressive grasp of blues, psychedelic rock and even

elements of jazz and without sacrificing its vaunted stage

energy. By early 1969, the U.K. success of “Undead” and

news of Ten Years After’s incendiary club gigs, had

kindled interest across the Atlantic.

Promoter Bill

Graham invited the group to come to America and perform at

both Fillmores, East and West. Such acceptance helped spur

U.S. sales of “Stonedhenge”, the groups third disc, and

led to an invitation to perform at the Woodstock Festival.

The band enjoyed a warm reception from the massive

festival audience that August 1969 evening. But, it was

the inclusion of a frantic, extended rendition of “I’m

Going Home” featuring Lee’s inspired. Screaming guitar

solo in the documentary “Woodstock” released nine months

after the show, that elevated the group to stardom. “I

know first hand that it was the release of the film that

broke Ten Years After in America,” remembers Lee. “We did

the festival, and it was a very special event and a great

time, but it was just another gig, on a long American

tour. After the festival, we went for nearly a year

performing in venues like the Fillmore East and Fillmore

West, until the movie came out, and that’s when all the

ballyhoo took place. The silver screen does make things

larger than life. That film rocketed us into the stadiums.

A lot of people say that’s what made the band, but in a

lot of ways, it was the beginning of the end, as it wasn’t

much fun playing arenas. Ten Years After moved to the

forefront of the British Blues Movement. “SSSH” and 1970’s

“Cricklewood Green” along with “Watt” each broke

Billboards Top 30, while the earlier albums, “Ten Years

After” and “Undead” enjoyed steady U.S. sales, being

re-discovered by a wealth of new / younger admirers. By

1971, the incredible pace of the group’s success seemed

to have spiralled out of control. Coupled with a rigorous

touring schedule, they recorded four albums in just two

years. This ran in marked contrast to Lee’s own personal

ambition. “I was looking at longevity,” Lee recalls. “My

heroes were people like Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker.

Today, Hooker’s close to 80, and he’s still playing. I

never wanted to be a pop star, because it seemed so

tasteless and short-lived. I knew very early on, that I

wanted to be a working musician, not a rock star.”

Adamant about

being given enough time to prepare for the group’s next

album, Lee won an uneasy truce for 1971’s “A Space In

Time.” “That title came from me digging my heels into the

ground,” explains Lee. “I told my managers and agents that

I wouldn’t work because I needed time to create good

music. I took six months off to write, because I was tired

of writing lyrics in the back of a taxi on the way to the

studio, then acting as if I had the tunes under wraps for

months. The songs for the first two albums were drawn from

our live repertoire. We already knew these songs well and

knew they worked with our audience.

When we got to

albums three and four, I suddenly had to start writing new

songs, and it was hard to get those songs up to the

quality of the ones we had been playing in our live gigs.”

None-the less,

Lee’s investment paid off handsomely, as the rejuvenated

Ten Years After, on the strength of the album’s hit

single, “I’d Love To Change The World,” enjoyed its

largest selling effort to date. When Lee was vindicated by

the resounding success of,

A Space In Time,

the album’s impressive showing increased the call for

more albums and longer tours. “I didn’t like the so called

big time,” admits Lee. “When Ten Years After first started

to happen in America, it was great. We were playing places

like the Fillmore’s or the Electric Factory and the

Kinetic Playground and those were great gigs, playing

before two thousand people. Later, however, it grew into

playing ice hockey arenas and stadiums, and I hated that.

The music was secondary. People weren’t really listening

to the music, and I was playing to an orchestra pit full

of cops and security guys with their backs turned and

cotton wool in their ears. I was thinking to myself, what

am I doing this for? The answer at the time should have

been money. But the peace of mind that I needed was much

more important than the money. I knew too many people who

had gone under or cracked from that kind on pressure.”

Equally ironic was that while Lee struggled with the

concept of rock stardom, his love for live performance

never diminished.” “Live gigs are what keeps me going.”

Says Lee simply. “It’s in my blood, I put up with all the

travelling and hotel life because it’s part of the

pleasure of performing for people. These days, I actually

find touring easier and more enjoyable. In the early

years, I think I made things hard on myself. We would do a

twelve week tour and I wouldn’t want to work again for

three months. But I’ve learned to pace it more now, three

weeks on, one week off. That way, over a year’s time, you

do more work without having to endure the grim side of it.

If you do more than three weeks at a time, the

performances lose their spontaneity. With Ten Years After,

I used to look at tour itineraries on paper and wonder how

I would live through them, it would just seem so

daunting.”

By 1973, with the

group’s spirited blues rock a staple of then “Underground

F M” stations throughout the U.S. Lee made his move as a

solo artists. Bolstered by the likes of George Harrison,

Steve Winwood, and Mick Fleetwood, Lee joined company with

American vocalist Mylon LeFevre to record 1973’s prophetic

“On The Road To Freedom” album. His heart set on

establishing a solo career, Lee still rallied Ten Years

After to record 1974’s

“Positive

Vibrations”, the group’s swan song. At the close of an

extensive American tour in 1975, Ten Years After formally

disbanded. (although no one officially admitted it).

His reputation

firmly established, Lee began touring and recording under

the umbrella of Alvin Lee and Company. In 1978, the

guitarist formed Ten Years Later, recording two acclaimed

albums, “Rocket Fuel” and “Ride On” before resuming his

solo career once more in June of 1980. Save for a one-shot

Ten Years After reunion in 1988, Lee remains content to

shoulder the load on his own. One notable exception,

however, came in 1981, when former Rolling Stones

guitarist Mick Taylor was recruited to the fold. This unit

toured Europe and the U.S. Reviews of their scintillating,

duel guitar interplay fostered hope that the two might

formalize the partnership and possibly record. Sessions

were held in 1982, but the tapes, says Lee, remain

unfinished and unreleased. “Taylor is such a superb slide

player,” remembers Lee. “We worked well together.” Where

many of his successful contemporaries have struggled to

accept lower profiles and diminished sales significance in

the 1990’s Lee thrives within the parameters he

established. Rather than simply replicate the high-speed

fret-work memorialized by the Woodstock film,, Lee has

continued to refine his sound and style.

“I Hear You Rockin´”

is Lee’s strongest effort in years, attributable to, he

says, a dogged, back-to-the-roots approach to writing and

recording. “Recording this album as I did was almost a

revelation for me,” says Lee. “Normally, because I have a

home studio, I make demos. It takes me about for months to

create fifteen new demos. I’d play them to the band, but I

wouldn’t get any real input from them. They would just try

to assimilate what I had already done as best they could.

This time around, I sat with the band in a room, picked up

my guitar, and played my song ideas to them. This way, the

band joins in, and if a song works in the room, then it’s

going to work live. It’s always been an ambition of mine

to record an album and walk on stage and say, “I’ve just

recorded an album, and here it is for you. With this

album, that’s what I’ve been doing and it’s been a real

buzz!” As so much of Lee’s sound and style is derived from

his raw, charged live performances, it comes as little

surprise, that he chose to capture that same spirit by

recording the album’s basic tracks live in the studio.

“You have to keep

the technical side of recording studios from taking over,”

argues Lee. “You have to keep

the technical side of recording studios from taking over,”

argues Lee.

“They put the drummer in one room and the guitar player in

another. You can’t even see the guys you’re working with.

Okay, you get a clear sound, but with my kind of music,

it’s the feel that’s important, not the sound. If there

are a few glitches and rough edges, fine, I like that. You

can not beat the eye contact of sitting around and looking

at each other, playing off one another.” “I Hear You

Rockin´” also continues Lee’s intriguing collaboration

with long time friend George Harrison. Harrison guest on a

spirited remake of the Beatles “I Want You” and lends a

salacious slide guitar to Lee’s own, “Bluest Blues,” a

dark moody ballad and the album’s strongest track. “I

first hooked up with George in 1973. when he wrote and

played “So Sad,” a song he wrote for “On The Road To

Freedom,” my first solo album. Following that I played on

George’s “Dark Horse” and 33 1/3 albums for him. Since

then we’ve become very good friends. He’s played on the

last three solo albums I’ve done. I don’t play slide well

and he’s very good, so I call upon George. It’s getting to

be a bit of a tradition, I only wish I could get him out

there with me!” With, or without Harrison in tow, Lee

shows no signs of slowing down. He’s currently formalizing

plans for yet another extensive American tour. “Hey, he

laughs, “I hope I’ll still be at it when I’m 80. It’s a

bit too late for me to get a proper job at this point in

my life, don’t you think?”

|

Collection - CD (record label Griffin) - Nov 1994

|

NIGHT

LIFE – By Bill Logey, Special To The Times

From

November 3, 1994 Article Written

The

Concert Was On November 5, 1994

Los

Angeles Times 2010

Alvin

Lee, the “Guitar God” of Ten Years After, Ventura (California)

– Bound. He plays “Basic Root Blues” high energy and he

doesn’t neglect the memory songs for his fans of yesteryear.

Attention

parents: Be careful who you bring home to your impressionable

offspring. If you were to invite Willie the Wino, Jack The

Ripper or The Pillsbury Dough Boy to the house, well, who

knows what strangeness may ensue?

Now,

once upon a time in scary olde England, the Lee’s brought

home famous blues dude “Big Bill Broonzy” and their boy,

young Alvin, ended up being a “Guitar God” fronting

“Ten

Years After”. Alvin Lee made several hit albums, millions of

dollars and drew plenty of rock fans who couldn’t get enough

of that wailing guitar.

Now,

nearly Thirty Years Later, Alvin Lee returns with a new album,

“I Hear You Rockin´”, and a Saturday night gig at the

venerable Ventura Theatre. The new album is a throwback to Ten

Years After’s 1966 self titled debut album. It’s bluesy,

but not boring, because Alvin knows too many licks to induce

drowsiness. Alvin could also write those mean blues lyrics.

From

“A Sad Song” a sample line: “My face in the mirror,

reminds me of you. It’s the one that you lied to, when you

said you’d be true”. But Ten Years After, among other

things, is remembered for perhaps the most famous song,

“I’m Going Home” on the endless “Woodstock” movie.

Recently Alvin Lee, who speaks slower than he plays guitar,

talked to me by phone from a Rhode Island hotel room.

Q.

- Where’s the

old Ten Years After guys. Chick Churchill, Leo Lyons and Ric

Lee?

AL.

– We had a reformation in 1989 to support our “About

Time” release. But we closed that down after a few months.

It was kind of like getting back together with your ex-wife,

it’s fine for a couple of months. Leo, has his own band

called “Kick” the other two, I’ve lost track of.

Q.

– Ten Years After, like a lot of other British bands,

started out as a blues band. How did you get those blues?

AL.

– My father was always playing this ethnic blues stuff

around the house, and both my parents played. Then one day, my

father brought home Big Bill Broonzy, and there he was sitting

in our living room playing, and blues was in my heart, from

the time I was twelve years old. I took lessons for a year and

learned all the chords, and I had my first band when I was

thirteen, it was called, “The Jail Breakers”.

Q.

– What was it like making the jump from small clubs, to the

giant venues that you played with Ten Years After?

AL.

– It wasn’t very satisfying playing the big arenas, but it

was good as far as a pay check was concerned. But the sound

was terrible, especially in those hockey arenas. The sound

would go on for thirty seconds after we’d quite playing.

Also, they didn’t have security staff back then, but real

police officers with guns. You can’t hear anything, you

can’t see anything, except for the backsides of policemen.

It just wasn’t very conducive for having fun.

We

used to do songs like “Woodchoppers Ball” but these songs

didn’t work at all in a big room. Again, the sound becomes

really heavy and we loose the “Rock `n´ Roll. Then when

we’d play a little club, there’d be trouble outside,

because everyone couldn’t get in. I just wanted to enjoy

what I was doing, but I wasn’t enjoying that at all.

Q.

– So being a “Rock Star” in the 1960’s and 1970’s

was good or bad for you?

AL.

– Absolutely, good and bad. I always wanted just to be a

blues guitarist, and I don’t think I was quite ready for all

that went with it, and I had what they refer to as “Head

Problems”.

There

were a lot of responsibilities, especially with the media

which were so overwhelming.

I’d

do twelve of these interviews in a day. Then we’d tour for

three months straight, then get two days off, then they’d

call and say, “You’re in the studio next week – hope you

have the songs ready”.

Q.

- Ten Years After went away when you guys changed your record

labels and released “A Space In Time” In the 1970’s

(1971) What happened there?

AL.

– It was entirely coincidental. “A Space In Time” is

about the time off that I managed to take off, to work on the

album. They’d be telling me, “Alvin, you can make a

millions of dollars in the next six months”. But I thought,

“I just made a million dollars in the last six months, and

it’s not doing me any good”. Anyway, I thought I wrote a

lot of good songs for that album. No longer do I let the pace

of work interfere with the creative forces. This will be just

a five week tour.

Q.

– Do you still play Ten Years After songs?

AL.

– Of course I still do, and “I’m Going Home” is the

last song. But for awhile I quit playing it. When we’d do a

gig I could hear people shouting for “I’m going Home”

after the first song and I’d tell them, “So, go home then”.

You know, Jimi Hendrix got tired of playing “Hey Joe”.

Then in 1979 or 1980 I saw Jerry Lee Lewis playing in

Birmingham, and he was going through his country and western

phase at the time, and he didn’t do any of his hits, I was

very disappointed. It made me realize, that if I didn’t play

the songs that people wanted to hear, they wouldn’t want to

come back and see me.

Q.

– What’s Alvin Lee’s brand of blues?

AL.

– We were doing stuff that was called blues rock at the

time, then it became underground rock, then it was psychedelic

rock, but it was all the same thing, really. It’s basic root

blues, high energy. I don’t describe it, I just play it.

Q.

– I read a review once that said you were just “ten fast

fingers and a pretty face”. What did the critics get wrong

about you?

AL.

– I suppose it was the whole “Captain Speed Fingers”

thing, the fastest guitar player, and all that. I never tried

to be the fastest; I even tried to slow myself down. A lot of

these new guys can play ridiculously fast, but there’s no

light and no shade, and most of them run out of licks in a few

minutes, anyway. Sometimes, it actually sounds faster, if you

play slower.

Like

the song says, I want to keep on rockin´. Those old guys like

John Lee Hooker, who must be what, 80? And he’s still going

strong!

Details:

Alvin

Lee with Nine Below Zero

The

Majestic Ventura Theatre, 26 Chestnut Street

Saturday

8:00 PM

Tickets Cost: $16.50

|

| To Stay Happy, Guitarist

Alvin Lee Only Needs A Bumper Crop of Blues:

Article by Michael Kinsman - Staff Writer

Date Book:

Alvin Lee with Nine Below Zero, 9

tonight.

Coach House San Diego (formerly The Café)

10475 San

Diego Mission Road, Mission Valley. $16.50; 563-0024.

Reprinted from original article from the San Diego Union

Tribune from November 16, 1994

Alvin

Lee, the hell-on wheels guitarist best remembered for searing

the crowd with his impassioned blues-rock at the 1969

Woodstock festival, is looking for eye contact. On the verge

of his first U.S. tour in four years, he's spent only three

days practicing with the band Nine Below Zero, trying to get

the feel of the music. "Eye contact is very important to

that", the British guitarist says from New Jersey. "You

can know the music, but you've got to get the feel, too. A lot

of times if you see the eyes of the gentleman, you can see if

they're getting it. Some things just come with a nod and a

wink."

Twenty-five years after his incendiary Woodstock

performance with Ten Years After on "I'm Going Home",

Lee is excited by the prospect of still playing music for

people. "All I've ever gotten out of music is the

pleasure of playing it," says the 49-year old

singer-guitarist, who appears tonight at the Coach House San

Diego (formerly The Café in Mission Valley). "Everything

else is secondary."

Lee's finest public moment-the

scorching Woodstock performance-may have also been his most

distressing professional moment. "That was really sort of

the beginning of the end, strange as that sounds," he

says. "As soon as the movie came out, it sort of boosted

Ten Years After to another level. We started playing

ice-hockey arenas, and it started getting out of hand. "There

would be this horrible sound ringing around the roof of the

arena, and I'd be on stage looking at the backs of policemen

with cotton balls in their ears. I like places where you can

react with the audience, but that wasn't happening. I had no

feel." Lee said, the arena shows forced the band to

change its sound. "We sort of auditorium-alized it,"

he says, coining a term. "It was sad because that really

was the end of the band."

The band lumbered on the road

for a few years, eventually calling it quits in 1976. An

outgrowth of several years of teen-age experimentation, Lee's

Ten Years After had earned a reputation as a British blues

band in the mold of Fleetwood Mac and Savoy Brown and had

risen high to pop stardom in 10 years. "I never really

wanted to be a rock star", Lee says, "I just wanted

to be a blues player."

He remembers that his father

collected jazz and blues records, particularly chain-gang and

prison work songs. "I was pretty lucky, really, to be

growing up around that," he says. "My father

listened to traditional jazz, some swing…I guess he was

basically a bebopper. We had a guitar that he would fool

around with, but he couldn't play much. He would plunk on

it."

A key moment for him came the evening his parents

invited American blues man Big Bill Broonzy to their

Nottingham home after a concert. "I was 12 years old and

they woke me up," he says. "I was sitting on the

living-room floor looking up at this giant black man playing

blues. That's when I decided I wanted to play the blues".

Lee forgot his clarinet lessons and started learning guitar

chords. Soon enough, he heard a Chuck Berry record and knew he

was hearing his future. "Chuck Berry sought of brought it

together for me," he says. "He was the first guy to

put the energy into the blues." And while pop music grew

in the 60's to encompass social conscience, Lee was having

none of it. "Music should stand on its own," he says.

"I never liked those deep heavy messages. I liked the fun

in music. I'm sort of a Don't Step On My Blue Suede Shoes-Come

On Over, Baby, There's A Whole Lotta Shakin' Going On, kind of

guy.

Eventually, Lee's blues became supercharged rock,

dependent on his lightning-quick playing. "In a way, I

think I may have started this frenetic guitar-soloing stuff,"

he says. "They used to call me Captain Fast Fingers, but

I always tempered it with slow parts. The dynamics really are

what music is all about, not how fast you can play. What Lee

enjoys is playing guitar riffs that are melodic and graceful.

On his "I Hear You Rockin´ " recording released

earlier this year, he mixes his leads with the slide guitar of

friend George Harrison. Lee has been recording with Harrison

on and off since 1973 and until a few months ago lived only a

few minutes away from the ex-Beatle west of London.

"We

have the sort of relationship where we can pop in on each

other", Lee says. "I think he likes that because his

life is made of appointments. He doesn't have many friends who

drop in for a cup of tea, play guitar for 10 minutes and then

leave. We both seem to enjoy those moments."

Lee refused

to participate in last summer's Woodstock festival, fearing

that the magic of 1969 was being sold out to greed. "I

have good memories of Woodstock," he says, "but I

didn't want to repeat something that had been an accident.

This time it just seemed like there were a lot of people

trying to make some money. If they really wanted to have a

Woodstock festival, I think they should have had people like

Michael Jackson and Bon Jovi. The first Woodstock had all the

biggest names of the day. Why shouldn't this one?

For now, Lee

is happy to be playing music that people want to hear in cozy

clubs. "It's a good thing for that." He says. "It's

too late for me to get a proper job."

Note: The

concert was really a two night event, that took place on

November 6th and 7th 1994. The exact location was San Juan

Capistrano, California. The concert was recorded and released

as a bootleg, the cover of  which can be seen

below. which can be seen

below.

Alvin Lee's

backing band, Nine Below Zero at that time consisted of:

Garry McAvoy (ex Rory Gallagher) on bass guitar

Brendan O´Neil on

drums

Alan Glenn on guitar and harmonica |

|

|