|

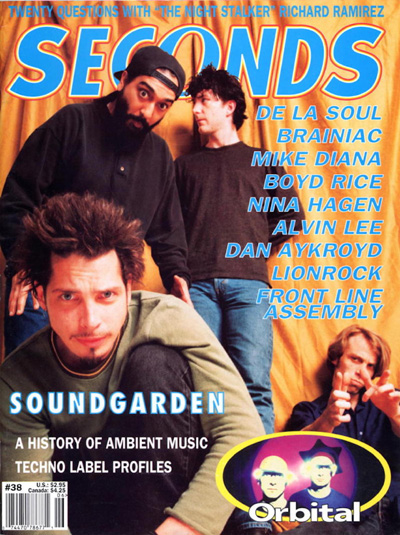

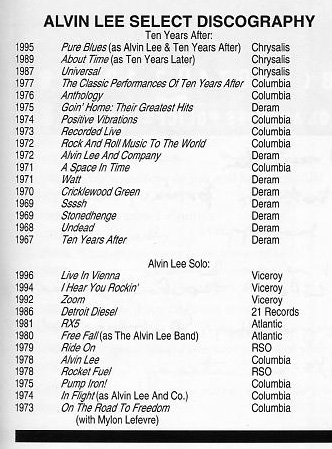

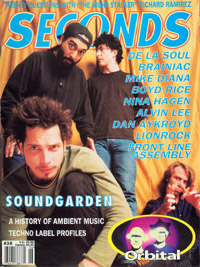

SECONDS

Magazine, No. 38 - September 1996

His music ought to be playing in

the lobby of the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame. He is

Alvin Lee, formerly of Ten Years After, later of Ten

Years Later, presently Alvin Lee again, someday to

be enshrined.

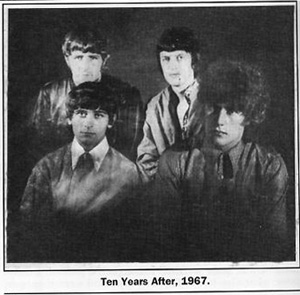

Ten Years After came as close to

being “underground” as a band could get in the late

Sixties.

They were raw and scruffily

flower-powered. Despite their down-the-road sound,

they aspired to virtuosity and speedy delivery. It

was a time when albums were becoming more important

than specific songs (thanks to the FM radio

revolution) and there was zero nostalgia in music

marketing, the Blues being something new to the

White market. Ten Years After, who cranked out

unfolding jams for hours on end and mixed genres

with ease, were perfect for the emerging expansion

of styles and attention spans. They enjoyed

substantial recognition due to the sophistication

and curiosity of the day’s audience. Lee’s unique

guitar frenzies demanded that often – very often –

he was mentioned along with contemporaries Eric

Clapton, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page (after all, he was

one of the fastest and most fluid guitarist in the

business).

You’ve heard Lee do his thing as

Ten Years After’s big hit “I’d Love To Change The

World” echoes Muzak – like over the drone of our

planet, where no clatter can drown out his soaring

post-Psychedelic guitar riffs that served as

prototypes for many later mainstream Metal

styling’s. And you’ve heard Ten Years After_s

Woodstock workout of “I’m Going Home”, in which

Alvin Lee lays down some of the fastest Blues in

history. But, what else do you know?

Long Before Ten Years After’s

Woodstock Showcase, Alvin was a teenage Blues Wizard

in early Sixties England, even playing with John Lee

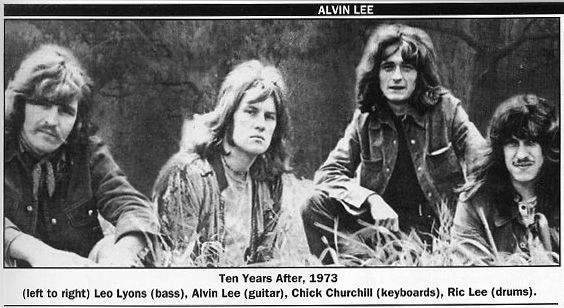

Hooker in London. Alvin paired up with bassist Leo

Lyons for gigging in an array of groups such as The

Jaybirds and Britain’s Largest Sounding Trio.

Drummer Ric Lee joined Alvin and Leo in 1965, after

which they persued a sound with an emphasis on Hard

Blues. Two years later, with keyboardist Chick

Churchill in tow, the assemblage had released a

self-titled album as Ten Years After on Deram

Records.

Subsequent recordings like Undead

and Stonedhenge were not huge sellers but were

highly regarded discs that established Ten Years

After in the burgeoning Rock underground.

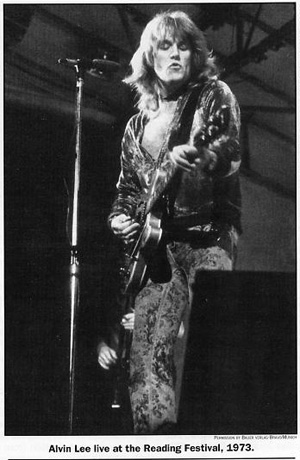

In the year prior to Woodstock,

they wowed audiences at the Fillmore West and New

York’s (Steve Paul) Scene Club with a Hyper-Blues,

that was equally kaleidoscopic and pyrotechnic.

Growing out of the underground,

post-Woodstock Ten Years After became a marketable

commodity and jumped from Deram Records to Columbia.

After 1971’s “A Space In Time” and 1972’s “Rock and

Roll Music To The World”, Alvin and crew had moved

up to headlining status in America’s biggest

venues.

But Alvin was reluctant to assume

“Rock Star Stature”. He instead

built a studio in his home and with White Gospel

Singer

Mylon LeFevre recorded an album

entitled “On The Road To Freedom” (1973 – on which

superstars such as Steve Winwood, George Harrison

and Ron Wood guest-stared on).

By 1974, Alvin Lee had obviously

enjoyed his time away from the Rock & Roll ruckus of

Ten Years After – so much that he put together a

nine piece band around Mel Collins and Ian Wallace (both of King

Crimson). They recorded a Live Album

of non Ten Years After material, and called

themselves, “Alvin Lee and Company” and the album

“In Flight”.

However, while Alvin’s solo

adventures were taking place, managers, lawyers,

booking agents, girlfriends, and of course his

band-mates were consumed by thoughts of all the

money that could be made by getting Alvin back into

the lucrative American coliseum circuit, blazing

through “Going Home” just one more time. So Ten

Years After re-grouped and recorded one final record

album called “Positive Vibrations”. After a

“farewell tour” at the beginning of 1975, Alvin

started anew; the next six years saw The Alvin Lee

Band release albums such as: Pump Iron, Free Fall

and Rocket Fuel.

The Seventies turned into the

Eighties and you know that story; Punk Rock, New

Wave, Electro Pop, Rap and all the rest – but Alvin

continued to boogie right through it all.

During that period, playing in

Alvin Lee’s group was one of the best gigs an

old-school rocker could have. Down on their luck

musicians like ex- Rolling Stones guitarist Mick

Taylor and ex-Stephen Stills Manassas bassist Fuzzy

Samuels found gainful employment with Alvin.

After 1981’s RX5 album, Alvin was

not ready to make the move into hi-tech AOR pabulum

like so many of his English contemporaries – so he

did nothing and passed his time at home.

If he had the urge for a jam

session, he could always ring up old chums like

George Harrison, who guessed on the sturdy Detroit

Diesel album released in 1986.

1989 marked the return of the

original Ten Years After line-up under the sardonic

name

Ten Years Later for a reunion

album on Chrysalis. (note from Dave – Ten Years

Later was the name of Alvin’s solo band and had

nothing to do with Ten Years After).

About Time was the name of the

new album and subsequent Ten Years After tour. It

was a pleasant affair for those involved, but there

was an apparent oldie-but-goodie “Remember Us?, look

to it all. Not looking to go the eight shows at the

amusement park route, Alvin detached himself from

the Rock Conglomerates and joined up with the New

York based label

Viceroy. Nineties recordings on

Viceroy like “I Hear You Rockin” and “Zoom” rate

among his strongest works.

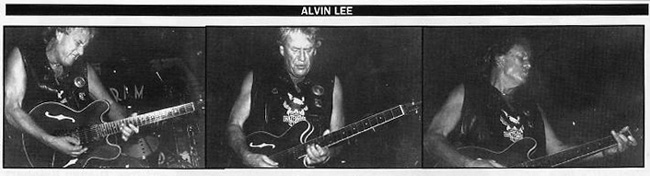

Today you’ll find Alvin touring

the world not on the Rock Revival Circuit, but

rather in small and sweaty Blues Clubs. Presently

accompanied by fellow travellers Eric Burdon and

Anysley Dunbar, Alvin plays good-time Rockabilly to

an older but reverent and musically educated

audience who are there, Not For Goin´Home – but to

see Alvin Lee and his guitar roam the plains of the

great American Blues.

The Interview With Alvin Lee:

Seconds: What aspect of your work do

you recognize in music today?

Alvin: Licks and tricks,

really. There’s certain licks I play that I know

I’ve developed that not many other people play. I

never used to copy players. I was a big fan of Chuck

Berry, but I never copied his solos. I’d emulate his

style. Sometimes I hear my actual licks copied. I

realize there are some young guys out there

listening to me, like I listened to Chuck Berry.

That’s an on-going thing.

Seconds: You are particularly noted

for playing fast.

Alvin: The original

“Captain Speed-Fingers” yeah. That was something

that just happened, actually. I never tried to play

fast. If anything, I tried to slow it down a bit.

With the adrenaline of live gigs, it just used to

come out that way. I never acknowledged that

“Fastest Guitarist In The West”

and all that because it just isn’t true. Django

Reinhart was before us all and played much faster

than anybody I’ve ever heard. A lot of Jazz players

like

Barney Kessel and John McLaughlin

play much faster than me. I’ll play light and

shade,

I’ll play things slowly and then hit you with some

rocket riffs. It’s nothing I set out to do – it’s

quite the opposite; I always tried to hold it back a

bit.

Seconds: What other

qualities of your guitar playing would you like to

be remembered for?

Alvin: I just play by feel,” from the hip”, as they say these

days. I’m

not musically trained.

I’ve been asked to do one of

these “Hot Licks” type tutor-videos and I’m not sure

if I’m the right man for the job, because I never

really know what I’m playing. I’ve developed a style

where my fingers will do what my brain says, but I

don’t get in the middle of that. It’s one of those

things where I grit my teeth, dig in, and just play

it. It’s an automatic thing. It doesn’t work

slow; I

forget where I’m going. I don’t play scales or

anything like that – in my mind, scales are a waste

of time. You learn to play a major scale but you

can’t use it !

It doesn’t sound nice. What’s the

point of learning to play something that doesn’t

sound nice?

So I make my own scales up. I

make scales that I want to hear. It sounds better

and I can use it. I don’t think about my playing too

much. I don’t sit down and practice this lick or

that lick, I just play.

Seconds: What’s the

center of gravity, the thing you come back to the

most?

Alvin: The center of

gravity is the guitar and me.

Seconds: I hear the

word Rockabilly in connection with you….

Alvin: Yeah, I was a big

fan of Scotty Moore. I met Scotty in Nashville. I

had to say to him,

“That second solo in “Hound Dog”

– how did you play that?” He said, “I just grabbed

a handful. I’ll tell you about another time I fucked

up….” It was a mistake. That’s what I like about

Blues and Rock N´ Roll – sometimes the mistakes are

the great bits. You make a mistake and it sounds

good. That often happens when I’m playing live. I

told Scotty a lot of us guitarist were trying to

work out how he played this second solo to “Hound

Dog,” and it’s a complete mystery, even to him.

Seconds: You don’t like your

music to be too polished.

Alvin: I’m kind of an amateur

engineer. I’ve got my own twenty – four track studio

and I’ve always fooled around and made demos. Over

the last ten years, I’ve got more and more involved

with drum computers and synthesizers and sequences.

It’s a lot of fun, but it led me astray a little

bit. On the “Zoom” album, there’s a song called

“Jenny Jenny”. It pleased me because it sounds like

a Rock & Roll tune, but it was actually cut with a

drum computer. On “I hear You Rockin;” I listened to

some old Ten Years After songs and said, “How did we

record then? How did the songs come about?” I

remember sitting with the band in one room and

playing tunes, so that’s what I did on this last

album. It’s simple, but I clouded by technology.

When I first started touring after I made the album,

I did something I’ve always wanted to do. I went

onstage and said, “I’ve just made a new album and

now I’d like to play it for you”. I played the whole

album from start to finish and it was great. Now,

I’m playing a mixture of old favourites because I

think the audience would like to hear the classic

cuts, as well as the new stuff.

Seconds: What do you regard as

your classic stuff?

Alvin: “I’m Going Home” – “Love

Like A Man” – “Good Morning Little Schoolgirl” –

“Slow Blues In C” – I’ve just started doing “I Hear

You Calling” again.

Seconds: How was Ten Years After

different from other Blues Rock bands of that time?

Alvin: Ten Years After was never

a very happy band. It was a constant war, which made

the style what it was. I was playing rocket riffs,

the bass player (Leo Lyons) was playing rocket riffs, the

drummer, (Ric Lee) was playing a constant

drum solo, and a lot of the time it was very

frustrating. I wanted to hear a bit of backbeat, but

the band was so busy – every-time I’d take a solo,

everyone else would take a solo at the same time.

Seconds: But you had the final

word, right?

Alvin: Yeah, to a point. I never

told a musician what to play. It’s far too

corporate. If you want a happy musician, if you want

a contribution from the guy, he’s got to be playing

what he likes.

Seconds: Yet you were together a

long time….

Alvin: It was enjoyable, but I

started to move toward solo projects because I

wanted to move on and I to try other things. The

first solo album I did was. “On The Road To Freedom”

(1973) – which was a little statement in itself, and

it was basically Country Music. It was a whole

different feeling. I had Ian Wallace playing simple

drums and Boz Burrell from (King Crimson and Bad

Company), who was one of my favourite bass players.

After playing with Ten Years After, where everything

was a racket and solos, suddenly I was playing with

Wallace and Burrell. I’d start a Rock n´ Roll

song,

and instead of them coming crashing like I was used

to, they’d come in with a neat half-time feel. To

me, that was great. I’ve always liked to do

different things; I don’t like to get stuck in a rut

too much. I’ve always experimented with music. I

hate the kind of person who sits down and says,

“What’s popular?

What the people want to hear,

I’ll play that”. That’s too contrived. I always like

the music I play. I’ve gone astray a few times, I

must admit. Record companies say they want you to

record something that’s popular so it can get played

on the radio – I tried it a few times and it never

works. The radio stations say, “This isn’t Alvin

Lee’s stuff. We want the real Alvin Lee. “I’ll stick

to my guns and play what I like and it’s more

rewarding. If you do have some success and it’s come

from your heart, it’s much more rewarding.

Seconds: Ten Years After albums

were very referential to Psychedelia, but they were

also Blues albums.

Alvin: That was all part of that

Sixties feel. On the second album, Ten Years After

did, the live album called “Undead” we just played

in a club and recorded it. I heard it back a couple

of days later and thought, “This is great”. This is

the band playing the best they’ve played. Where do

we go from here?”

I was quite worried, I thought I’d

peaked. I didn’t know what else to do. The way my

mind went then was, “I’ve done that, so let’s

experiment in other regions”. I suppose the

Psychedelic era was on us and I was playing around

with mind expansion as much as anyone else, and I

guess it just came out in the music. I was always

trying to not get tied down by any particular bag.

Seconds: Was the drug scene an

integral part of the music?

Alvin: Not integral, but

inspirational in a way.

Seconds: Did that all

change?

Alvin: It has now for me – but

not that recently! I’ve been a heavy user for a long

time. I only cleaned up my act quite recently.

Seconds:

An intoxication ritual

is a great motivator for music.

Alvin: It is and it isn’t.

Inspiration is hard to get, and anywhere you can get

it, you get it. I’ve never been into heavy drugs at

all. I was a pot smoker, I took LSD, and I found LSD

to be quite inspirational.

Seconds: Did you do it when

playing live?

Alvin: I have, in the bad old

days. Once at the Fillmore West, as I walked on

stage, the chemicals took over. I hit a test note on

my guitar and I heard it hit the back of the wall

and hit everybody’s head on the way back and bounce

up. Most of what I remember about this gig is what

people told me afterwards. I know I played “Slow

Blues In C” and then said “Now I’d like to do Slow

Blues In C and played it again. All the fans were

giving me very strange looks. There was one point

where I was playing this solo, finished the solo and

thought, “What song is this?” I came back playing

another song. I got away with it, nobody wanted

their money back. Things like that tended to happen

at the Fillmore West.

Seconds: Did drugs take a toll on

your contemporaries?

Alvin: When people started to

die, that was not funny. I’ve always been very

against heavy drugs. I’ve never been in the same

room as Heroin. If anybody ever started to strap

their arm up, I’d make it known that I disapprove

and walk out. I’ve seen too many go that way. But

smoking pot is harmless. Acid’s probably a bit

risky, but you can’t be too safe in this world, can

you? I was quite a late starter in drugs. I never

wanted to be reliant on anything. I liked the way I

was going and didn’t want to change anything. The

first time somebody gave me some Speed Pills, I was

so worried that I made myself sick and spewed them

out.

Seconds: Do you consider Cocaine

one of the heavy drugs?

Alvin: I don’t consider it

heavy,

I consider it a waste of time and money.

Seconds: Did you see its effect

on people around you?

Alvin: Yeah, I was a late starter

on that too. I used to say, “How stupid putting

white powder up your nose”. Eventually, I started

doing it myself, as well. That led to three day jam

sessions, out of which nothing came except a lot of

rubbish. There was a time where I thought, “I don’t

see the way out of this,” and suddenly I got fed up

with the stupid lifestyle and just stopped. I’m

healthy, happy, and I’ve got something in the bank

now, which I never did when I was into that stuff.

Seconds: Your sound became more

complex with albums like “Watt” and “Cricklewood

Green”.

Alvin: I think an important part

of music is evolving, and the band evolved, not

necessarily for the good, but I think it’s best that

a band does evolve, rather than stand still. We

could have played that same style and become a

cardboard cut-out band and made enough money to live

fine, but I wanted more than that. I wanted personal

creative rewards; I wanted to feel I was doing

something more important than making a living.

Seconds: And the offer to play

Woodstock……

Alvin: That just came about in

the middle of a tour. I didn’t recognize it as

anything different until I got there.

Seconds: It was a real

demarcation point in your career.

|

Alvin: In retrospect, yes, but it

was the movie that did that. The band was playing

the Fillmore West, Fillmore East, Kinetic Playground, Boston Tea Party…..the

underground. We’d

play to 1,000 to 2,000 people at the most. They’d be

right up front, sweat dripping down the walls. Some

of the best gigs I’ve ever done were those kind of

gigs.

We played the Woodstock Festival

– great experience – but for a year we carried on

playing club gigs. It wasn’t till the movie came out

– that silver screen, larger than life feeling, and

suddenly I found we were playing basketball stadiums

and ice hockey arenas. You’d think playing to 20,000

people in arenas is making it, but it was horrible,

I hated it. Having played clubs all my life, I

suddenly found myself in ice hockey arenas where

you’d finish the number and the sound continued on

for another thirty seconds – huge barriers, so you

couldn’t see the audience – and in those days, they

didn’t have security guys; they had real cops with

guns and cotton wool in their ears. I was playing to

the back of coppers heads and thinking, “What am I

doing this for?” People were shouting for “Going

Home” through every number, and I got very

disenchanted with that.

|

|

Seconds:

If you didn’t enjoy

playing the arenas, who was making you do it?

Management and Record Companies?

Alvin: Pretty much. I wanted to

do it at first. You think that’s what you want; you

have to actually get it to find out it isn’t what

you want. I used to walk onstage with everybody

screaming and shouting – it didn’t seem like I had

to do anything. With everything I did, they weren’t

really listening to it. Nobody was picking on it.

I’d play a rotten show, everybody would come back

afterwards and say it was great. I’d play a good

show, and everybody would say it was great. I don’t

think anybody really knew. Generally I wasn’t

getting any feedback. It’s a very unreal situation.

My hero’s are Blues Musicians and I was becoming a

Pop Star, which I didn’t want. A lot of people will

say Woodstock made Ten Years After, but in fact it

was the beginning of the end. At that point,

disenchantment went on. To me, it was a big trap.

I was constantly plagued by media

obligations; it was ridiculous. I was doing twenty

interviews a day and by the time it came time for

the gig, I didn’t know where I was. I actually made

the decision to de-escalate that thing. I stopped

it. The managers, the record companies the agents,

they all said, “Alvin, you can make millions of

dollars”. I said, “What’s the point of having

millions of dollars if I’m crazy?” I didn’t want

what was happening to me.

I stepped out of it and there’s

no regrets. I’m playing a club tonight and that’s

what I love doing. I’m glad I’m not playing Madison

Square Garden tonight.

Seconds:

Tell us about “A Space

In Time”.

Alvin: A Space In Time was me

making a break. After the Woodstock Movie, I had no

time to write songs. I was writing songs in the taxi

on the way to the studio. The band would say,

“What do you got” and I’d make a

song up right there. It worked; it was natural. I

still write songs like that nowadays, but at the

time I thought it ought to be harder than that. I

wanted to struggle, I wanted to sit up all night

writing. So I said, “I want six months off to write

songs”.

That was the first time I heard,

“But Alvin, you could make a million dollars in the

next six months”. Nobody could understand I didn’t

want that.

Seconds: How was the band

politics concerning money?

Alvin: Everybody was a bit burned

out with these auditoriums, to be honest. I wasn’t

the only one. The other guys quite liked making lots

of money, whereas I thought it was distasteful, I

didn’t think I deserved it. With A Space In Time, I

said I was taking six months off. I wanted to be

proud of the music I made. “I’d Love To Change The

World” was one of the songs on that album I was

really happy with.

Seconds: On The Road To Freedom

with Mylon LeFevre was a real departure from the

Ten Years After sound.

Alvin: I was trying to get back

to some sanity and get away from Rock & Roll. When I

did that, I realized that wasn’t what I wanted

either and I came back to Rock & Roll. I went to see

Jerry Lee Lewis and he was playing Country &

Western. He didn’t play “Whole Lotta Shakin” or

“Great Balls Of Fire” and I was really

disappointed.

I came out of that gig and I thought, “If people

come to see me and I didn’t play “I’m Going

Home,”

they’re going to come out of the gig feeling like I

feel”. It’s ok being an artist and playing what you

want, but if people are paying money to come and see

you, then you’ve got to give them something of what

they want. That night, I went back to my band with

Ian Wallace and Boz Burrell and said, “We’re doing

I’m Going Home tonight”. I finally came full circle

and came back to

Rock & Roll and found it’s what I

did best.

Seconds: It seems you’ve managed

both your fame and your money pretty well.

Alvin: Yeah, by the skin of my

teeth.

Seconds:

You’ve probably had

former millionaires looking to borrow ten bucks from

you.

Alvin: It happens, sure. If you

want security, there’s no security in the world. If

you’ve got a million pounds, somebody can steal it

from you. The only security I’ve ever found as a

musician is that I can sing for my supper. I can do

a gig and make money to live.

Seconds: Did you have

contemporaries that lost their resources and looked

to you with resentment?

Alvin: Most of those guys didn’t

care. They were so out on a limb, they didn’t

realize what they had and when they lost it, they

didn’t realize it either. You make the best of what

you’ve got, don’t you? It’s not so much the guys

that made millions and lost millions , it’s the guys

that made millions and never got it. There’s lots of

that, guys that had hit records and never saw a

penny because of their crooked manager. I was lucky,

I had a manager who used to say he was ninety

percent straight, so I figured I got ninety percent

of the money coming to me.

Seconds:

How about your

subsequent band, Ten Years Later?

Alvin: The name in itself was an

anniversary, it was ten years after, Ten Years

After. There was a time around 1973 when I didn’t

have any interest in the band anymore and the

manager said, “You could have any musicians you

want, Just call it Ten Years After. Keep the trade

name”. To me that was very distasteful. I wanted to

leave that and start again.

Seconds: I get the idea that you

just considered yourself a guitar player in a group

called Ten Years After, and were bothered by the

fact that people fixated on you.

Alvin: It was never intended to

be that way. It was a communal group, but obviously

the singer and lead guitarist will be in the

spotlight ninety percent of the time. I was getting

bad vibes from the rest of the band. They were a bit

miffed, that I was becoming the front man.

That really started the rift

within the band; they wanted to do interviews, too.

So the manager would say, “Chick Churchill’s going

to do the interview instead of Alvin Lee,” and the

people would say, “We don’t want him, we want

Alvin,” and the resentment built.

Seconds:

In your current music,

what do you look for?

Alvin: The feel. If it feels

right, it’s good.

Seconds:

If you experience a huge

resurgence of popularity and someone calls you up

saying,

“Alvin, we want you to play

Madison Square Garden,” what will you say?

Alvin: I’d probably do it. I’ve

learned a lot of lessons. Now I’ve got control, I

know what I’m doing. In those days, I didn’t know

what I was doing. I was pretty lost and the drug

haze didn’t help. When you get to my age, you learn

to make things easier for yourself. When you’re

twenty three, you seem to be intent on making things

hard for yourself – “How many drugs can I take and

still play?” I’d give playing Madison Square Garden

a whirl, I’d try and put over my music the way I

want it to be. But I don’t think there’s too much

danger of that happening.

|

|

#38 (September 1996)

|

|