|

TEN

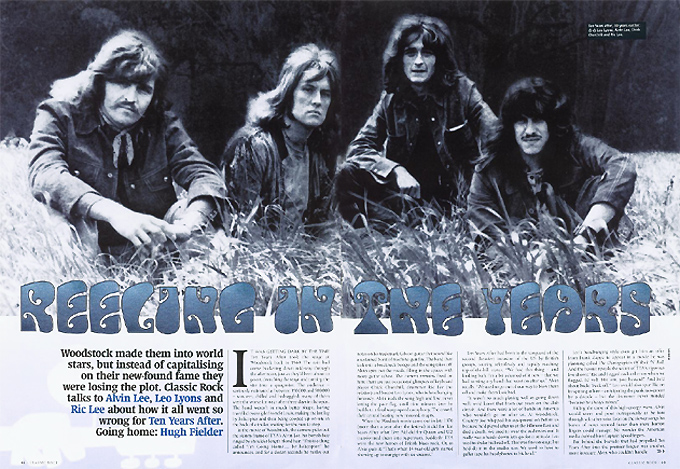

YEARS AFTER – REELING IN THE YEARS:

WOODSTOCK

made them into world stars, but instead of capitalising on

their new-found fame they were losing the plot. Classic Rock

talks to Alvin Lee, Leo Lyons and Ric Lee about how it all

went so wrong for Ten Years After.

Going

Home:

Written

by Hugh Fielder (Modified Corrections by B & D)

From

the August 2003 issue of Classic Rock Magazine

It

was getting dark by the time Ten Years After took the stage at

Woodstock back in 1969. The rain had come bucketing down

mid-way through the afternoon, just as they’d been about to

go on, drenching the stage and turning the site into a

quagmire. The audience variously estimated at between 350,00

and 500,000 was wet, chilled and bedraggled; many of them were

the worse for wear after three days in the open.

The

band weren’t in much better shape, having travelled

overnight from St. Louis, making the last leg by helicopter

and then being cooped up on-site in the back of a trailer,

waiting for the rain to stop.

In

the movie of Woodstock, the camera picks out the skinny frame

of Ten Years After’s Alvin Lee, his boyish face ringed by

shoulder-length hair. “This is a thing called “I’m Going

Home” by helicopter!” he announces, and for a dozen

seconds he rattles out notes on his trademark Gibson guitar

that sound like a sustained burst of machine-gun fire. The

band then kick into a breakneck boogie and the song takes off;

Alvin spits out the vocals, filling in the spaces with more

guitar salvos. The camera remains fixed on him; there are just

occasional glimpses of keyboard player Chick Churchill,

drummer Ric Lee (no relation to Alvin) and bassist Leo Lyons,

who is head banging furiously. Alvin leads the song high and

low, never letting the pace flag, until nine minutes later he

builds to a final warp-speed cacophony. The crowd, their

central heating now restored, erupts.

When

the Woodstock movie came out in late 1970 (more than a year

after the actual festival) it did for Ten Years After what

Live Aid did for Queen and U2; it transformed them into

superstars. Suddenly Ten Years After were the new heroes of

British Blues Rock.

Or,

as Alvin puts it: “That’s when fourteen year old girls

started showing up to our gigs with ice creams.”

Ten

Years After had been in the vanguard of the second (and much

heavier) invasion of the US by British groups, touring

relentlessly and rapidly reaching top of the bill status.

“We had this thing – and looking back I’m a bit ashamed

of it now – that we had to sting any band that went on after

us,” Alvin recalls. “We used to go out of our way to blow

them off and make them look bad, it wasn’t so much playing

well as going down well; we’d learnt that from our years on

the club circuit, and there were a lot of bands in America who

wouldn’t go on after us. At Woodstock Country Joe McDonald

whipped his equipment on before us because he’d played after

us at the Fillmore East and died a death. We used to wear the

audience out. It really was a heads-down-let’s–go-for-it

attitude. (Alvin and Leo called it “Their Blow’em Off

Policy”).

Leo

used to shake his head off, that was fine on stage, but he’d

do it in the studio too, we used to have to gaffer-tape his

headphones to his head.” Leo’s head-banging style even got

him an offer from Frank Zappa to appear in a movie he was

planning called “The Choreographers Of Rock “n” Roll.

Leo reveals the secret behind Ten Years After vigorous and

intense live shows: “Ric and I egged each other on when we

flagged (slowed down a bit, and needed that edge back) I’d

yell “Hit them you bastard!” and he’d shout back:

“Fuck Off.” Leo would also spur Ric on by spitting at him

– anticipating the punk movement by a decade – but the

drummer never minded as Ric says “because he always missed”.

Riding

the crest of this high-energy wave, Alvin would sneer and pout

outrageously as he tore through solo after solo. Even on the

slower songs his burst of notes seemed faster than mere human

fingers could manage. No wonder the American media dubbed him

“Captain Speed-fingers.”

But

behind the bravado that had propelled Ten Years After into the

premier league was another, more insecure Alvin Lee who just

couldn’t handle the superstar status that the Woodstock

movie had bestowed on the group: “We’d been playing for

the heads, the growing underground audience”, he recounts,

“ But then it got bigger and people had to come to ice

hockey arenas and stadiums to see the band, and because of

this, we lost the personal connection with the (our) audience.

“You had police with guns and cotton wool sticking out of

their ears, sneering up at the band and looking for half a

chance to beat up some unfortunate and unsuspecting audience

member. It was awful, and at this point I realized that it had

all gone wrong and I found myself thinking, “what the fuck

am I doing here?”

And

the song that made Ten Years After famous was becoming an

albatross (a ball and chain): “You’d walk on stage and

people would be shouting for “I’m Going Home”, which was

the last song in our set. I often wonder what the rest of our

career would have been like if the Woodstock movie had used

another song. As it was, everything became focused on the last

song, which also happened to be our most high energy number

and show topper”.

To

make matters worse, Alvin was also becoming estranged from the

rest of the band members: “I think they began to resent me

because I started to back off then,” he admits,

“I

couldn’t help it, I hated it, I just hated all of it, I used

to go on stage and go; “dong” (as he mimes a big chord)

and the audience would go “YeaHHH!” You could do anything,

it was just crazy, it was horrible. “My problem was that I

couldn’t communicate it to anybody, as my band mates thought

I was Looney, as I went into sulks and things like that, maybe

I should have tried

to talk more with them, but it didn’t work for some reason,

they started to get jealous because they thought I was being

singled out to do all the interviews and the photo sessions. I

wasn’t getting singled out, I was the songwriter, singer and

lead guitarist, after all, so obviously I was the one they all

wanted to talk to.”

There

was indeed resentment from the rest of the band, but it was

born out of frustration rather than jealousy. Around the time

of Woodstock, Ten Years After’s management had decided to

focus all the attention on Alvin, which is fair enough you

might think, as it was Alvin who was the front man, the guitar

hero and the pin up poster image. But Leo Lyons and Ric Lee

believe differently, to them (and they should know better than

anyone else) “Alvin was temperamentally unsuited to assume

the role: “I felt it would be too much pressure for Alvin,

and told our manager, Chris Wright, that he was creating a

monster he couldn’t control,” Leo says.

Their

misgivings were well-founded, because at the very moment that

Ten Years After should have been seizing the initiative, Alvin

retreated behind a wall of dope smoke. Whenever Ric and Leo,

angry at being marginalised, managed to provoke a reaction out

of Alvin it was invariably the wrong one. It created a rift,

and the recriminations continuing to this day.

What

added to the bitterness was how close the group members had

been up to then. Ric describes Alvin and Leo’s relationship

as “a well-oiled marriage”. It dates back to 1960 when Leo

started playing with Alvin, already a precocious guitarist, in

a local Nottingham band called “The Jaybirds”. They even

went through the classic 1960’s rock group apprenticeship

together, playing a five week stint at Hamburg’s Star Club

in 1962 – just a week after the Beatles played there.

According to Ric Lee, “We stayed in a two-room apartment

above a mud-wrestling / sex club,” Ric remembers. “The

rooms were filled with bunks and there were probably ten or

twelve people living there. I was eighteen, Alvin was

seventeen, and we were exposed to prostitutes, pep pills and

music twenty four hours a day.” Alvin confirms that the

Hamburg experience was “a real rite of passage, as one day I

went into the bathroom and there was one bloke sitting on the

toilet, a guy in the bath and another guy washing his socks in

the bath water, when all of the sudden another bloke runs in a

fires off a gas gun into the room – it was total madness.

There was also a scary side to it with the gangsters. One guy

had this big welding glove and when you used to see him going

out with it you’d think: “Uh-oh, trouble.”

When

the band returned to England Alvin bought his first Gibson

ES335 – which would become his trademark guitar. Ric, who

came from nearby Mansfield, replaced the previous drummer

(Dave Quickmier) in 1965 (as it was Quickmier who personally

recommended that Ric take his place in the band) and soon

afterwards they brought in Chick Churchill on keyboards. The

following year they started tapping into the burgeoning blues

market in Britain that John Mayall had opened up. “I threw

myself headlong into that,” says Alvin who had grown up

listening to his dad’s collection of pre-war bluesmen such

as Big Bill Broonzy,

Lonnie

Johnson and Josh White, but it was the jazzier influences in

the group that meant they were always, as Ric says, “a bit

sideways-on to the blues”.

That

paid off when Chick Churchill got them an audition for

London’s then legendary Marquee Club early in 1967 and

equally legendary club manager John Gee who was very impressed

by their version of Woody Herman’s “Woodchoppers Ball”.

To celebrate, they changed their name from the now outdated

Jaybirds to Ten Years After – which Leo found while flicking

/ leafing through the pages of the Radio Times Magazine.

Via

the Marquee, Ten Years After landed a spot on the 1967 Windsor

Jazz and Blues Festival (which later became known as the

Reading Festival), where they got a standing ovation from

20,000 people in attendance. Among them was noted blues

producer Mike Vernon, who was there checking out one of his

charges, Fleetwood Mac. It was Vernon who later signed Ten

Years After to Decca’s new Deram label (which ironically,

the band had just recently failed their audition for Decca).

In

keeping with the times, Ten Years After slapped down their

very first record album in just five days, and “Mike could

see that we were a bit radical as far as his kind of blues was

concerned.” Alvin recalls, “but he basically gave us the

freedom and said get on with it.”

The

album caught Ten Years After’s raw, jazzy approach to the

blues, which could be high-velocity, as on the opening song

“I Want To Know”, or the slow, extended and mood building,

closing number called “Help Me”.

The

record was rough and ready, but it attracted the attention of

famed American concert promoter Bill Graham, who was looking

for new bands to play at his Fillmore venues in San Francisco

and New York and figured there must be more where Cream and

Hendrix had come from.

In

June of 1968 Ten Years After started a seven-week US tour at

the Fillmore West: “That first tour was great”, Alvin

recalls, “We had such a good time out there, and we lost

around $35,000, but we got asked back so we knew we were on

our way. The strange thing was that we had gone to what I

considered to be the home of the blues, but they’d never

heard of most of them, and I couldn’t believe it – “Big

Bill who?”

We

were recycling American music and they were calling it the

English sound, while all the American bands were using Fender

equipment, which sounded really tinny when compared with the

juicy sound that you get from Marshalls.”

Then,

of course, there were the psychedelic delights of the West

Coast, and Ten Years After had already been a part of the

London underground scene during 1967’s “Summer Of Love”;

they had even made a whimsical trippy single in early 1968

called “Portable People”,

and played at the very hip Middle Earth.

Publicity

shots of the time reveal Ten Years After’s garish fashion

sense: “Ah, Paisley shirts!” Alvin laughs, “That was my

girlfriend, Lorraine, she was the wild one, as she had me

wearing my mother’s curtains for trousers, with those

lampshade frills around the bottom.

“I

loved the underground,” he says. It was so experimental ,

everything opened up, and you could try anything (and it all

was accepted) and by now the drugs were taking effect, and

that was all part of it – the opening up of consciousness.”

In

America, you had to be careful not to find your consciousness

being expanded unwittingly.

“There

was one gig at the Fillmore West,” he remembers, “where

somebody gave me this joint as we were going on stage, and me

being Mr. Bravado, I had to have a toke – and it turned out

to be angel dust, and by the time I got to the stage, my left

leg felt a mile long.

I

hit the first note on my guitar and it struck the back of the

hall and I saw it bounce back hitting the heads of the

audience and ricochet up into the roof, and I was just

standing there going: “Wow”. I don’t know how I managed

to play, but I noticed at one point the band were looking at

me strangely. After we finished the song I said: “What’s

wrong?” and they replied: “We just did the same song twice!”,

but it didn’t matter as the audience were in the same state,

it didn’t seem to matter.”

Needing

a new album to promote the band, Ten Years After hastily

recorded a live album at a club called Klook’s Kleek in

London. “Undead” caught the sweaty, small-club vibe /

atmosphere and the band’s free-form approach to the blues

with the jazzy, flashy “I May Be Wrong But I Won’t Be

Wrong Always” and “Woodchoppers Ball”, the intense

emotional blues of “Spider In You Web” and a very early

yet potent version of “I’m Going Home”.

“Basically,

that album put it in a nutshell,” Alvin reckons, “I was so

happy with it, when I first heard it I thought, what are we

going to do next? After that my attitude was, “Let’s go

into the studio and experiment, because we’ve already made

the ultimate album.”

The

result of that initial experimentation was the not-so-subtly

titled “Stonedhenge” (with all due credit being given to

Alvin for the very apt title) as it was Ten Years After’s

“Psychedelic Blues Album” Alvin’s recollection is

“Pipes and stuff like that all over the place” and it was

very experimental in places. I was into my musique concrete

phase. There’s quite a lot of (avant-garde industrial

composer) Todd Dockstader in there. It was still very

underground at that point, and we were making music for that

audience / for ourselves really because we were that audience

too.”

”Stonedhenge” could fairly claim to be Ten Years After’s

most innovative album, as it’s light and trippy (their

“Flower Power” album, reflecting the time period or the

insistent “Going To Try” and the ever bouncy / catchy and

addictive hook of “Hear

Me Calling”, or the positively spooky lyrics / tone of “A

Sad Song”. Despite, the apparent substances involved behind

the scenes, and in common use during this period – the band

itself were tight, strong and confident.

Stonedhenge

was released in February of 1969, the record set up Ten Years

After for a momentous year. In fact Woodstock was just one of

half a dozen festivals they played that summer, which also

included Texas, Seattle, and the prestigious Newport Jazz

Festival, which also proved to be the only year that rock

bands were allowed to participate.

At

Flushing Meadow in New York they played alongside of Vanilla

Fudge and Jeff Beck. While Led Zeppelin also turned up to

check out the competition. In Richard Cole’s notorious

“Stairway To Heaven” a kiss and tell all book, the former

tour manager relates how Jimmy Page was awestruck by Alvin’s

super-sonic playing, much to the annoyance of an inebriated

John Bonham, who suddenly lurched forward and threw a glass of

orange juice all over Alvin’s guitar, in order to slow up

his (Alvin’s) finger work as the strings and fret-board got

stickier.

When

asked about this incident, Alvin doesn’t remember anything

having been thrown, although Ric Lee confirms the story. He

also remembers a more amusing incident at the end of the show

when he and Bonzo joined Jeff Beck for the encore: “There

was Robert Plant, Rod Stewart, Jimmy Page, Jeff Beck and three

bassists I think Bonzo was beating out a riff on the drum kit,

so I grabbed a floor tom and started thrumming hell out of it.

The crowd were going ape-shit as we banged out a blues

standard and Bonham, who was already stripped to the waist,

took off his trousers and underpants. He was sitting there

naked, playing away, when the police saw him, I then saw Peter

Grant and Richard Cole spotting the police as the number

fizzled out, all I saw was Peter and Richard running on stage,

each grabbing one of Bonzo’s arms, and his bare arse

disappearing as they carried him off.”

Alvin

tended not to get involved in the rock n´ roll high jinks,

however: “ The reason I didn’t mix with bands like Led

Zeppelin and The Who too much and go in for all that hotel

wrecking was that I was a doper; I was always carrying hashish

around, and in those days you could get twelve years if you

got caught with a joint in somewhere like Texas.

Even

legal drugs such as alcohol could also be hazardous for Alvin,

particularly if they were being brandished by someone like

Janis Joplin: “She used to chase me around a bit,” he

chuckles,” but I wouldn’t have it. She was just too

dangerous.

“There

was a show we did with them at the Fillmore East and they were

handing her bottles of Southern Comfort on stage and she was

drinking them, I thought it must be something like sweet wine.

She came off stage and grabbed my ass and gave me a bottle, so

I promptly collapsed and passed out in a quiet corner. When I

woke up it was about five in the morning and there was just

some guy sweeping up, and I didn’t even know which hotel we

were staying at.”

In

fact, on the Richter scale of rock groups behaving badly, Ten

Years After barely registered (“I tried to start a food

fight one night, and everyone went “behave yourself.” Ric

admits). So it’s something of a surprise to find them

appearing in the grossly overrated movie “Groupie”.

In

a scene that attempts to prove guilt by insinuation, Leo is

seen with a young lady in a hotel coffee shop, ordering tea,

while the soundtrack plays Ten Years After’s “Good Morning

Little Schoolgirl”. “Oh boy, was my friend Iris pissed off

when she saw the movie,” Leo laughs, “ Someone sent me a

copy recently, and I watched it while hiding behind the sofa

with one eye closed, but it’s pretty tame stuff now. The

musical segments are worth watching, but Spinal Tap would be a

better buy for the backstage antics.”

It

was Ten Years After’s SSSSH album, recorded just before they

embarked on their US summer tour in 1969 – that included

Woodstock and the other festivals – that opened up the rift

in the band. The album itself wasn’t a problem, after the

laid back trip of “Stonedhenge”, Alvin was up and flying

again; his blistering solo on “I Woke Up This Morning” was

a corker / cooker, as was the reworked riff that anchors

“Good Morning Little School Girl” was tougher than the

rest. The problem was the album sleeve, which in Ric’s words,

“stuck it to everyone, as we’d done a photo session

together and then suddenly we were presented with this album

cover with just Alvin on the front, and we went: “What The

FUCK Is This?”

“This”

was the new management strategy of putting the focus on Alvin,

and Alvin admits the pressure got to him almost immediately:

“There’s the story about how I nearly didn’t play

Woodstock because I had a bad back, it wasn’t a bad back, it

was a bad head. I couldn’t face the tour, I looked at the

thirteen week list of dates and thought, I’m not going to

get through this. “I pretty much had a nervous breakdown at

the beginning of the tour, I’d done five days of interviews

before it started, I’d left my girlfriend back in England,

and I really wasn’t feeling very capable and I just

collapsed.

It

was our American manager, Dee Anthony (who went on to manage

Peter Frampton), who got me through it. He used to give me all

these pep talks – “Stay on the bus, it’s your music,

forget all the bull-shit, that one and a half hours on stage

is all that counts”, but I was still getting upset, and I

was still going on stage saying: “This is Horrible.”

Nevertheless,

the relentless schedule continued and successfully too. The

twenty-eight US tours they notched up between 1968 and 1974

were unequalled by any other British band, and the album sales

were also getting bigger.

“CRICKLEWOOD

GREEN” may not sound as exotic as “ACAPULCO GOLD” or

“LEBANESE BLACK” admittedly, but then the grass always

seems greener on the other side

doesn’t it?

Cricklewood

Green, (the record) was released in 1970 cracked the American

top twenty and was Ten Years After’s biggest selling UK

album, helped by the hit single “Love Like A Man” which

Alvin remembers writing most of the songs in a taxi on the way

to the studio, (while the music riff was credited to Leo

Lyons).

“WATT”

was released at the end of the year, but failed to make any

substantial impact, but Alvin got what he wanted, time off in

which to write songs for the next album, called “A Space In

Time” and he came up with the band’s biggest hit, the

deceptively simple, catchy but out of left-field “I’d Love

To Change The World”. It became the crucial opportunity for

the band, “but by then I was too confused to take it,”

Alvin says, “I’d Love To Change The World” was a hit and

I hated it because it was a hit, by then I was rebelling and I

never played it live, to me it was a pop song,” Even worse,

Alvin vetoed the record companies choice for the follow-up

single, which annoyed the head of their US label, the

redoubtable Clive Davis, who had earlier told the band:

“Give me the tools and I’ll do the job”, promptly made

“I’d Love To Change The World” a Top Ten Hit.

Ric

remembers being invited to a Columbia Records meeting chaired

by Davis, with all the radio promotions people saying that

“Tomorrow I’ll Be Out Of Town” was a perfect radio cut.

When Ric said the band didn’t want that as a single, Davis

growled: “So why is that track on the album? If you want me

to do the job, don’t give me the tools and then take them

away from me.” “He’d been on our side up until then,”

Ric says, “But after that the albums never sold as well and

we never had another hit. If the artists didn’t co-operate,

then the record company would simply move on to one that did;

they weren’t going to wait around for us to get our act

together, and this was a stark lesson in reality,”

Not

that even Clive Davis could have done much with “Rock and

Roll Music to the World” which was recorded and sold pretty

much on auto pilot, and while “Recorded Live” fared much

better, it also highlighted the fact that the core of the set

list had remained unchanged since Woodstock four years earlier.

“What’s the point?” was Alvin’s response. He didn’t

have the inclination, he was miserable and communication

within the band was generally reduced to “Shouting and

screaming matches”.

Leo

contends that Alvin in turn made the band’s lives a misery:

“It stressed me out so much that I stopped trying to

reconcile things, I still enjoyed playing live shows, provided

there were no tantrums. If there were confrontations, I

stupidly rose to the bait every time.”

Amid

such an atmosphere, the management kept their distance, and

eventually Ten Years After took a six-month break for the

second half of 1973.

Alvin

recorded a solo album with gospel singer Mylon Lefevre (who’s

band “Holy Smoke” had supported them on tour) at his newly

furnished home studio, Mylon was great, he arrived and said:

“Where do all the musicians hang out?” I told him the

Speakeasy. He went straight off and returned about six hours

later and said: “I got us a band”, and in walked George

Harrison, Steve Winwood and Jim Capaldi! Mylon really had a

silver tongue, he captivated everyone.” Harrison even goaded

Alvin into putting on his own gig. Alvin: “He said: I’ll

bet you couldn’t,” and I did, I rang up and got a booking

at the Rainbow Theatre. I had twenty four songs that hadn’t

worked with Ten Years After , and I rehearsed them with a band

that included Boz Burrell, Tim Hinkley and Mel Collins.”

The

titles of the Mylon Lefevre album – “On the Road to

Freedom” and Alvin Lee & Company live “In Flight”

both seemed to offer broad hints about Alvin’s intentions,

but surprisingly, there was a new Ten Years After album due

out in 1974, called ironically “Positive Vibrations”

Except that it wasn’t.

Alvin

didn’t seem to know what he wanted: “I did an American

tour with Alvin Lee & Co. and it was all new material; I

didn’t play “I’m Going Home” or any of that. We were

playing little theatres, getting good reviews, but to tell you

the truth, I did miss the oomph of the audience, I’d gotten

used to that. I mean they enjoyed it and clapped and stuff,

but there wasn’t the oomph there, then I did a Ten Years

After tour and got the oomph back.”

Not

for long though. Another petulant spat resulted in a threat to

put the band on wages. They limped through one more US tour

before it all disintegrated. Alvin then embarked on a solo

career as Alvin Lee & Co. – The Alvin Lee Band – Alvin

Lee and Ten Years Later and even just plain old Alvin Lee.

Meanwhile,

the others got on with music-related careers, playing,

sessions, producing, managing.

In

1983, Ric Lee got a call from the Marquee presuming that Ten

Years After would be playing at the club’s 25th

anniversary celebrations. “I rang around the others and said:

“I think we should do this”. Alvin felt, “It showed us we could do it, and it was fun

actually, we had one rehearsal in the afternoon and then we

plugged in and played and it was Ten Years After. That amazed

me, and we thought that from that gig there would be a reunion,

but it didn’t happen, as it was a funny time in music, we

weren’t respected legends, we were old farts.”

Ten

Years After petered out when the bickering started up again.

It also hampered subsequent reunions at the end of the

1980’s and late 1990’s which included a nostalgic

appearance at the Woodstock 29th anniversary

festival, which was billed as “A Day In The Garden”. Their

reactions to that are revealing:

Alvin

Lee: “It was a big disappointment, there I was, standing in

a field that they tell me is exactly where it happened, but

the people weren’t there, the vibe wasn’t there, it had

nothing to do with it.”

Leo

Lyons: “It turned out to be a series of flashbacks for me,

we were booked into what used to be the Holiday Inn, Liberty

– Tranquillity Base in 1969. I didn’t realise until I

walked into the hotel bar, it stopped me in my tracks, I swear

I could see and hear Jimi, Janis, Jerry Garcia, Bob Hite, all

of them gone now. We were together in that room twenty nine

years ago.”

Ric

Lee: “Disappointing, really. We hadn’t played for awhile,

I was certainly rusty, the original thing was funky, this was

all very clinical, it was like an MOR concert. Still, at least

we had dressing rooms, which we never had the first

time….”

For

Ten Years After, it all came to a head at the last series of European Festival shows in 1999,

when a vicious spat between Leo and Alvin buried any chance of

a reunion, under a mound of perceived grievances on all sides.

Alvin went back to his own band, while the others remained

together, occasionally playing and recording with various

American guitarist.

However,

five things are directly related to the resurgence of interest

in the band:

1. The reissue of the Ten Years After Catalogue on cd format

2. A new book by Herb Staehr called “Alvin Lee & Ten

Years After – Visual History”

3.

The release of a lost or misplaced Ten Years After Fillmore

East Concert from 1970

4.

This website – That we started in 2001 and dedicated to Ten

Years After and its members

5.

Popular demand – fan request – fans desire to see the band

perform live – and recordings

These

five things prompted Leo Lyons, Ric Lee and Chick Churchill to

revive the band once again last year (2002). This was due to

the fact that when asked to join the band Alvin turned them

down flat / cold, so they went in search of a new guitarist

and found one via Leo’s son Tom, who told his father about a

“shit-hot” guitarist that he’d known in school.

Enter,

twenty five year old Joe Gooch.

Says

Ric Lee about Joe: “Initially I was sceptical because of his

age,” he admits, “but as soon as I saw him play I had no

doubts.” A couple of European dates last autumn convinced

all the band that Joe was the man to replace Alvin. Joe,

“has his own style but can still deliver all the Ten Years

After hits,” Ric says. The new-look Ten Years After are

playing British dates this summer, with an album to follow in

the autumn.

And

what about Alvin? – Alvin finds the current Ten Years After

situation “very sad”. Ten Years After used to be a

credible name and I was proud of it,” their former guitarist

says, “Now it’s just an embarrassment, I asked them to

change the name slightly, so as not to confuse the fans, but

they refused.”

Alvin,

who has just recorded an album with Elvis Presley’s original

backing musicians, guitarist Scotty Moore and drummer DJ

Fontana (“my teenage heroes”) in Nashville, and

tentatively titled “The Real Thing” (but became Alvin Lee

in Tennessee) also reckons that

“it’s a shame the new guitarist, who must be

pretty good to play my licks, is copying somebody else’s

style instead of playing his own music. If I had taken a job

copying somebody else’s music when I was starting out, there

would never have been a Ten Years After.”

|